During the summer, the Beni Hasan raised rice and millet, and in winter, barley and wheat unless prevented from doing so by either lack of rain or a greater flood than usual. They cultivated vegetables—especially a kind of spinach, turnips, onions, beans, eggplant, and some tomatoes on land near the banks of a canal or the edge of the marshes. The young leaves of many wild plants were gathered and eaten raw as salads.

Fields for crops were usually protected by manmade ramparts of mud and straw that varied in size according to their location. Those areas against the marsh bank or along the borders of a canal were usually significantly higher than those farther from the water. The largest bank in the area, in a place especially prone to flooding, stood about 3 m high and about 4 m wide at its base. Maintaining these embankments during the rainy season was a constant chore. The vegetable garden for some families was small, growing just enough for family use. For other families the area of the garden was larger and the produce was sold or bartered. Most Beni Hasan also had small herds of sheep, flocks of chickens, and sometimes turkeys and small herds of cattle. The sheep produced meat, wool, milk, and dung, the birds both meat and eggs, and the cattle meat, dung, milk, butter, and cheese. Fish, largely carp netted in the marshes, provided many families with their major income or trade good.

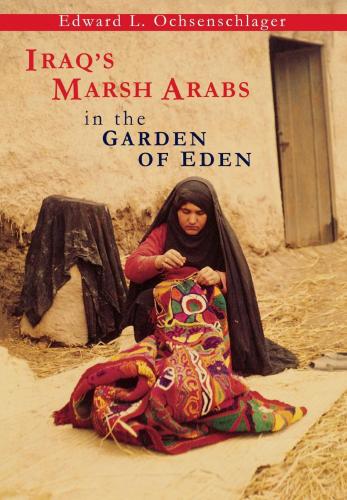

Then as now men wore a kuffiya (headcloth) fastened on their heads with a plaited camel hair or wool cord, and a dishdasha (long, straight garment) under a recycled western suit jacket, which is in turn covered with an aba (wool cloak). Underwear, consisting of white cotton drawers with drawstring waists, came midway between the knee and ankle. Very few people regularly wore shoes, except on holidays and other special occasions. So callused were men’s feet that they warmed them in winter by putting them on the hearth an inch or two from the burning coals. All men carried rifles over their shoulders, wore colorful ammunition belts around their waists and often over their shoulders, and carried a mugwar (reed and bitumen club). Women wore an abaya (shapeless black cloak) that covered them from head to foot. Under the cloak they wore a loose-fitting black garment similar to the dishdasha.

The Family

Family organization is patriarchal and patrilocal. The father is the head of the household, which usually consists of himself, his wife or wives, his sons and unmarried daughters, his sons’ wives, his grandsons and unmarried granddaughters, and possibly his sons’ sons’ sons, their wives, and great-great-grandsons and unmarried great-great-granddaughters. Usually the whole family lives in one compound or in two or more adjoining compounds (see p 100–101). In theory, the father has absolute power over his extended family. He decides which members of the family will perform which work, whom his sons and daughters would marry, what the living arrangements inside the compound would be, and how any extra produce for barter or money would be used. He is also the absolute judge of his family’s behavior, and he can punish them in petty ways by withholding food and privileges, and in substantive ways by disowning them or even having them killed or killing them himself. The most severe punishments are applied only in cases of extreme violation of honor. There was little to distinguish between exile and death: life without the family is considered a kind of living death.

The family is thought to have sharaf (a collective honor). The ideology of honor comprises responsibility—especially in obedience to religious laws—a strong work ethic, charity, chastity, and modesty. Each member of the family is responsible for the acts of every other member, and the dishonorable conduct of one member reflects upon the honor of all. Ideally men and women are expected to live by standards of conduct that reward generosity, sincerity, honesty, loyalty to friends, and vow keeping. Parents, of course, are supposed to instill these values in their children so they will grow up to be good Muslims. In addition, men are expected to provide financial support and to protect the family against external harm. Women must preserve their reputation for sexual morality by strict adherence to social mores, self-control, and modesty. If men fail in their obligations, their women lose honor. If women fail, men lose honor. Therefore “honor” is interlocked, and all members are responsible for the honor of the entire family or household. Much the same code of honor and sexual behavior is found throughout the Mediterranean and Latin America. It was brought to Spain by the Arab conquest and to Latin America by the Spanish.

Violations of the honor code are taken very seriously, and the threat of severe punishment seems to deter dishonorable behavior. In the villages with which I am best acquainted, exile, but not death, was occasionally inflicted. Out-of-wedlock pregnancy was among the greatest sins; its punishment was death to the woman by stoning at the hands of her relatives. I am aware of two such serious breaches of honor. In both cases the pregnant young women were sent to visit distant relatives and returned after several months to report that their distant married cousins had given birth to new babies. Neither of the two girls was physically harmed.

Despite evidence to the contrary, all inhabitants of the village knew—or pretended to know—that the death penalty had been invoked in a nearby village during their lifetime. The stories of these punishments were narrated in a very dramatic fashion, leaving one to wonder if these cautionary tales, true or not, were an important part of the deterrent.

On two occasions when problems of honor were not resolved through public discourse or through proper punishment exacted by the father, violence erupted. In one case, a young fisher boy spoke to a girl gathering fodder in the marshes. This conduct, regarded as dishonorable on his part but not on hers, since she had not answered him, was not adequately punished by the boy’s father. That night the girl’s family, armed with rifles, attacked the boy’s family compound and a battle ensued in which two people were wounded. To my knowledge, this case has not yet been resolved, and there is still bitter antagonism between the two families over an event that happened in 1978.

The second case, involving two families living in different villages, revolved around a boy who had blocked the path of a young girl and tried to make her speak to him. In the ensuing fight between men of the two villages who were armed with guns and knives, one member of the girl’s family was killed, and the transgression was only mitigated when the boy was sent into exile and a large payment exacted from the boy’s clan was paid to the girl’s family. This kind of payment commands the financial support of every clan member and often brings extreme hardship to more distant members who, even though they are not involved in the altercation, are obliged to pay their share. An unpaid obligation for a breach of honor may produce a blood feud that can continue for several generations. When a crime is committed against a member of another lineage, each member of the perpetrator’s lineage must pay in equal amounts his portion of the penalty. All men over 15 are considered as full members for the purpose of compensation, so a father of young men may have to pay several shares to satisfy his family’s portion of the penalty.

One of the problems that hampers ethnoarchaeological investigation among the people of al-Hiba is that men must be extremely careful in speaking to women to whom they are not related, since a woman who allows or encourages such conduct brings a serious stigma to her family’s honor. A good friend of the family might be allowed to speak to a widowed elderly grandmother, but only in public and only if she talks to him first. Indeed, several senior women relished the opportunity of expanding their knowledge of the outside world by asking me questions and at least two of them expressed interest in helping me find a suitable bride.

It is also quite all right for men to talk to little girls. Little boys and girls gathered around me wherever I went, intensely curious about the nature of this creature from outer space. They laughed, giggled, and asked questions, made hesitant statements or observations that brightened up my day. They were a beginner’s best teachers of Arabic for they had a limited but basic vocabulary and took delight in repetition. Although they often laughingly collapsed at my mispronunciations and other mistakes, they never tired of chatting and helping. Between the ages of 8 and 12, however, little girls grew up, spent more time at home, and were no longer supposed to socialize with boys or men. No male outsider was permitted to talk directly to a woman between childhood and old age. It