Taking Our Problem to the Villagers

Desperate for help in understanding these idiosyncratic finds, I turned to the nearby villages. The villagers soon introduced me to a world apart from the Midwestern U.S. farm where I was raised.

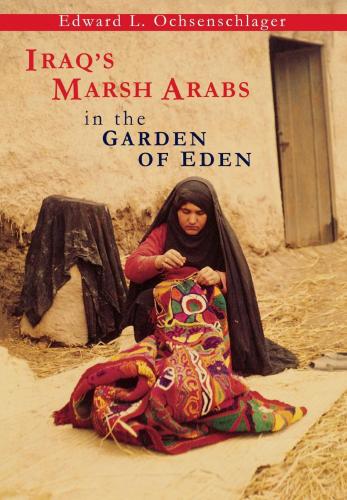

In 1968 a number of small villages existed close to the site of al-Hiba and alongside the marshes on which they were largely dependent. Each contained the homes of one of two different tribes, the Mi’dan or the Beni Hasan. The Mi’dan, sometimes called the Marsh Arabs, had lived in the marshes for over 5,000 years and fished the marshes with spears. They also kept water buffalo, which, technically undomesticated, foraged for reeds and sedge in the marshes during the day and returned to the family shelter in late afternoon to give up their milk and spend the night under protection.

Mi’dan villages were sometimes built directly in the marshes on platforms or islands they constructed of alternate layers of reed mats or reeds and silt dug from the bottom of the marsh. The Beni Hasan, in contrast, kept sheep and cattle of breeds adaptable to the environment, which grazed on the banks of the marsh, and raised crops of vegetables and animal fodder on plots of land that were sometimes irrigated. They also fished, not with spears but with set or throw nets.

There were many similarities between the two peoples, and families of one tribe were often dependent on families of the other. Both tribes kept chickens, caught wild birds in nets or shot them with guns, and grew rice in small beds on the edges of the marshes. Strict ideas of honor governed relationships between people. The principal guardians of these traditions, and the work ethic as well, were not holy men but craftspeople.

Children were born at home with the aid of midwives or an older female relative. They were taught early at their mother’s or father’s side the chores required for survival, and by the time they were eight years old they were productive and respected members of the family. One’s parents chose one’s mate, marriage occurred early, and it was expected that there would be no sexual activity of any kind by either person before the marriage was consummated. Most important, for our purposes, these modern people were largely dependent on the same material resources that had been available to the ancient Sumerians.

Answers to the Problem of the Mud Sherd

Imagine my surprise when I found villagers in every modern household using unbaked mud vessels alongside fired vessels and others made from metal, glass, and plastic. I spent hours watching village people collect mud and manufacture sun-dried mud objects. I also observed them use the objects for a wide variety of purposes: portable hearths, small storage containers, bases to stabilize large pots, corn grinders, incense burners—all were fashioned from mud and dried in the sun. Within a few weeks I was convinced by the evidence that ethnographic analogues had significant value for clarifying excavated finds and perhaps better understanding life in the ancient world.

Clearly I could not consider modern artifacts, similar to those that existed in Early Dynastic times, as an inheritance from the past. Nor could I conclude, on the basis of similar shape, that their functions were necessarily the same. It was clear, however, that the general ecology in 1968 Iraq was similar to that of the 3rd millennium BC. Our initial belief in this comparability rested on the archaeological finds of model boats, fishing spears and fish bones, the remains, impressions, or images of reed products or structures, and the like. The existence of such water-related artifacts in quantity seemed unimaginable without nearby, contemporary wetlands or marshes. Jennifer R. Pournelle brings certainty to this point of view in her dissertation.* She gives us an idea of what the southern floodplain would have been like in the early millennia of settlement and delineates the role of marshes as a recurring feature of the landscape. She believes that Sumerian administrators understood “that productive wetlands were not just those areas delimited by permanent reed swamp, but included all that surrounding area, seasonally dry, ‘created’ by farming and grazing, that revert to dust, mud, or water during a year’s progress,”* and this mirrored the ideas and practices of the modern people who inhabited the area at the beginning of our research.

Robert Ascher† had suggested that given environmentally similar conditions, valid analogies could be sought between the present and the past. Indeed, both modern villagers and ancient Sumerians had adapted to these conditions in a similar fashion: both used similar technology and the same locally available raw materials to make similar artifacts. I was convinced that what I learned from modern villagers would help me better understand the ancient Sumerians and might help the excavators answer archaeological questions at al-Hiba.

More Than Mud

What I learned about the modern use of mud§ was so interesting and so potentially informative about aspects of life in ancient times that I expanded my investigation to other materials that were used by ancient peoples. Initially I focused my investigations on wood, bitumen, reeds‡ and wool,§ and these carried me to tangential areas with which they were closely associated: wood to boats, fishing, and moral power of craftsmen; bitumen and reeds to the many kinds of tools and their use; wool backward to sheep and then to other animals and animal husbandry, forward to spinning, weaving, and the power of craftswomen in the community. The project had a single goal: to help us better understand what we were finding in the excavation. There was no expectation at that time that these studies would be of independent interest to anyone else.

This 22-year project resulted in a portrait of a way of life, however incomplete, which has since entirely vanished. From an archaeological point of view it helped us define ancient manufacturing processes and assign value to our artifacts as a function of the craftsman’s skill and time. It has extracted meaningful criteria to help us understand better an artifact’s significance, to appreciate the skill of those who used it, and to grasp the substantial social and moral authority wielded by village craftspeople. Study of the manufacture, use, and disposal of modern artifacts has indicated problems of interpretation sometimes overlooked in archaeological contexts. Above all, I believe these studies allow for a fuller understanding of the complexities involved in the process of change in an artifact’s function, value, and spatial relationships in defined settings.

Clearly many details of modern village life had parallels in the archaeological record. Arched reed houses and buildings of mud brick and pisé are well attested in antiquity, and we can conclude that they were built in a very similar fashion to the way they are built today, in part because of the nature of the raw materials and in part because of direct evidence of manufacture from ancient strata. Some of the forms of sun-dried mud pottery are attested in Sumerian times by finds in the excavations at al-Hiba, and they have preserved details of construction which show that they were made in the same way as modern examples. Mud storage containers, jars, conical ovens, ammunition for slings, and children’s toys are widely known in antiquity from many sites. Ancient models of outside mud and reed bed platforms, perhaps made as toys, show the same raw materials used in the same fashion as those in modern courtyards. Impressions of ancient reed baskets and mats exhibit the same construction techniques as do modern ones. Models of ancient boats show that