* Jennifer R. Pournelle, “Marshland of Cities: Deltaic Landscapes and the Evolution of Early Mesopotamian Civilization,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, San Diego, 2003. For specific details of the al-Hiba regions see 206–10.

* Pournelle, “Marshland of Cities,” 257.

† R. Ascher, “Analogy in Archaeological Interpretation,” Southwestern Journal of Anthro-pology 17(1961):317–25.

‡ E. L. Ochsenschlager, “Ethnographic Evidence for Wood, Boats, Bitumen and Reeds in the Southern Iraq: Ethnoarchaeology at al-Hiba,” Bulletin on Sumerian Agriculture 6 (1992):47–78.

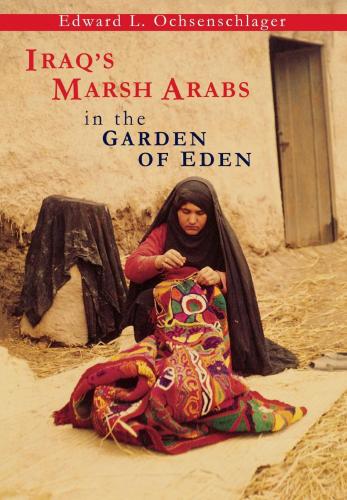

§ E. L. Ochsenschlager, “Sheep: Ethnoarchaeology at al-Hiba,” Bulletin on Sumerian Agriculture 7 (1993):33–42; E. L. Ochsenschlager, “Village Weavers: Ethnoarchaeology at al-Hiba,” Bulletin on Sumerian Agriculture 7 (1993):43–62; E. L. Ochsenschlager, “Carpets of the Beni-Hassan Village: Weavers in Southern Iraq,” Oriental Rug Review 15, 5 (1995):12–20.

* See Margaret Catlin Brandt “Nippur: Building an Environmental Model” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 49 (1990):67–73, for information on the alternating marshy and desert environment around Nippur.

* See Margaret Catlin Brandt, “Nippur: Building an Environmental Model,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 49 (1990):67–73, for information on the alternating marshy and desert environment around Nippur.

2

THE PEOPLE OF AL-HIBA

The people of al-Hiba lived far removed from the outside world. The trip to Shatra, the nearest town, was at its shortest when there was sufficient water in the main canal to float the large motorized boats which carried passengers, animals, and produce from the outlying areas to market. It still required a 2.5 hour trip aboard a motorized boat to a mud bank docking place and from there a taxi ride of 15 to 20 minutes. From January through March, during the rainy season, it took much longer since it was necessary to walk through deep mud from the dock to the nearest place approachable by taxi, a process that could take 1–2 hours. During the dry season, in late fall and early winter, the trip was longer still, 4 hours or more, since the villagers first had to walk to the place where the local canal joined the main Shatra canal (Abu Simech) from where they could hire a tarada (bitumen-covered boat poled through the water with long bamboo or reed poles) that would take them to the point where they could be picked up by the motorized boat. The motorized boat would then take them to the Shatra docking place.

Thus, people in the villages surrounding al-Hiba were relatively immobile. A trip to Shatra was a major event reserved for those occasions when they wanted to sell something—carpets, reed mats, wool, produce, an animal for butchering—that could not be sold or traded in the village, when they wanted to buy a major item such as a plow, a knife, or a gun, or when they needed to visit the doctor at the hospital. In most families the doctor or hospital visit was a desperate last attempt when other kinds of local treatment had failed. Villagers believed that sick people who went to the hospital inevitably died. They often delayed so long in taking a sick person for treatment that their beliefs became self-fulfilling prophesies.

The early years of our excavation, in the late 1960s, were times of unbelievable poverty for the people of al-Hiba. The sheikhs, who were politically active and prospered under the monarchy, were treated with great suspicion by the Baathists who used every opportunity to eradicate them and their influence, leaving a void in the management of farmlands. The irrigation system in the area, which had previously been one of the sheikhs’ major responsibilities, was now often in disrepair and inadequately regulated. Money was beginning to replace barter for some commodities, and people in the villages, who had little opportunity to acquire cash, were at a great disadvantage. In those days one could often see women gathering grass and sedge from the edges of the marsh and the canals, not for fodder for their animals, but to be boiled and served as the main dish for their families’ dinners.

The villagers in the area around al-Hiba fell into three different groups. First, the Bedouin pitched their tents on the seasonal marshland from late August to the beginning of the rains in late December. Second, the Beni Hasan dwelled in seven villages of 200 to 250 people each within walking or boating distance of the site. Third, five small villages of the Mi’dan, or Marsh Arabs, dotted the southern part of the mound. In addition three Mi’dan households, each isolated from the others, were perched on a narrow spit of land in the extreme southeast. Other villages of the Beni Hasan were located on the margins of the marshes, and some Mi’dan villages were found in the marshes where they had created patches of dried land by alternating layers of mud quarried from the marsh bottom with reed mats. All these settlements could be reached by boat.

The Mi’dan, or Marsh Arabs, have in particular attracted considerable attention. Fulanain (Hedgecock and Hedgecock) captured much of the atmosphere and social interaction in the marsh Arab world in a highly personalized account of a marsh dweller in The Marsh Arab Haji Rikkan (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1927).* Gertrude Bell, who had encouraged the book, was unable to write a promised foreword because of her untimely death. The Marsh Arabs (New York: Dutton, 1964), by Wilfred Thesiger, and People of the Reeds (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1957),† by Gavin Maxwell, provided very personal narratives of adventurous journeys through the same land. Both Thesiger and Maxwell were keen observers and wrote accurately, often poetically, of the lives and customs of the Mi’dan. Both works are also lavishly illustrated with fine photographs. The most useful account for the modern anthropologist is that of S. M. Salim (Marsh Dwellers of the Euphrates Delta (London: Athlone, 1962), a carefully documented field study conducted in ech-Chibayish (which lies at a considerable distance from al-Hiba) of the values and social rules whereby the lives of the Marsh Arabs are sustained, and it records the significant social changes in Mi’dan society due to commercial and external influence. It does not concern itself with the mechanical detail of material culture.

I am concerned here primarily with the material culture of the tribes living in the area, not only with the Mi’dan but with the Bedouin and the Beni Hasan, and I am especially concerned with their relations to each other. As the project originated in the desire to known more about our archaeological finds on the excavation, it is only natural that material culture should play the leading role, but that does not mean that other aspects could be ignored for they also had archaeological implications

Each of these three groups occupied an important ecological niche in the area, and all three had much in common. The general character and basic beliefs of each, especially in the area of family organization and patterns of living, were very similar. Rather than repeat fundamental elements common to each of the three groups, I shall describe first the Beni Hasan and note later how the Mi’dan and Bedouin differ from them.

Beni Hasan

The Beni Hasan, who belonged to the Shia branch of Islam, lived on dry land at the edge of the marshes. Only an occasional tribal sheikh preserved anything like the power he had previously possessed and he was strictly responsible to the government for every decision he made. Most of the local sheikhs had fled south, some as fugitives from government pressure, into Kuwait or even Saudi Arabia. Others had moved permanently to Baghdad where, through cooperation with the government,