With the onset of puberty, boys usually enjoy greater freedom than they had known in their youth. They are almost never punished now: they have learned to act according to the dictates of honor, to work well and industriously, and never to pilfer from members of friendly clans. When they complete their assigned work they are free to come and go as they please without explanation. Such freedom is considered necessary for men in order to develop self-control.

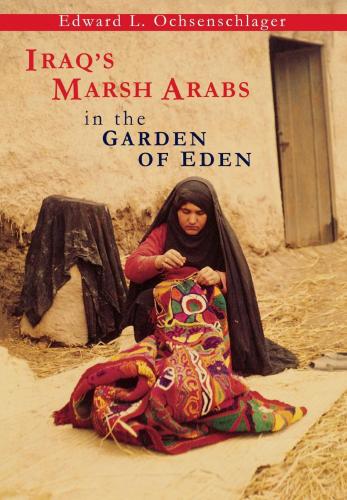

Girls, on the other hand, have their freedom restricted at puberty. Even a slightly sullied reputation seriously limits a young girl’s marital choices, if it does not preclude her marriage altogether. Therefore girls seldom leave the immediate neighborhood. When they venture out of their family’s courtyard they usually do so to work in their family’s fields or to collect reeds and sedges from the marshes near their homes. Even then they must wear the abaya and use it to hide their faces as well as their bodies.

In the area of al-Hiba where the dictates of religion are seriously adhered to, the onset of puberty can make life very difficult for young people. The Quran completely forbids any sort of sexual pleasure outside of marriage. There is no practice of masturbation, nor is there a word for it. One young man who worked for the excavation went into the most abject despondence I have ever seen, which lasted for nearly two weeks. When I inquired about the reason, Muhammad told me that the boy had exploded, that is, he had experienced a wet dream. His shame over this experience was acute. To avoid unwanted thoughts, it seemed to me, young men became punctilious about their religious conduct, spending their evening hours studying the Quran or singing religious songs.

Death

When an individual approaches death he or she is rolled onto their right side facing Mecca. Gunshots and the wailing of grief-stricken family members signal death. While the corpse is being washed by the womenfolk and wrapped in cloth, family friends go down to the banks of the canal to arrange transportation for the corpse to the huge cemetery in the holy city of Najaf, in southern Iraq, where those Shia who can afford it are buried near the tomb of the martyr Ali, son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad. Those whose families could not afford the trip, more women than men, were buried in a local cemetery. The dead person, whose family could afford it, was accompanied to the boat by male relatives and friends, shooting their guns and singing hosas of mourning. The ululation and mourning of the women could be heard from the dead person’s home where women wailed, scratched their faces with their fingernails, and heaped dirt on their heads. The bodies of men and those few women who were to be buried at Najaf were accompanied aboard the boat by grieving relatives and transported to the dock near Shatra. There a taxicab driver, who brought a wooden coffin, met the corpse, the coffin most often belonged to the driver, and he rented it to the grieving relatives for the trip to Najaf. The body was placed in the coffin, which was then lashed to the roof of the taxi for the trip. The deceased was accompanied by relatives, but fewer than those who had accompanied the body to the dock, for the number of mourners were usually limited to those who could fit inside the taxi. When the body reached its final destination, I was told, it was removed from the coffin and buried in the soil in its cloth wrapping. The owner of the coffin retrieved it and was free to rent it again. It was the responsibility of the members of the clan to assist with the expenses of transporting the body to Najaf and those of the three-day mourning period. All families who had either a relationship with the dead person or with other members of the immediate family were expected to attend the mourning ceremonies and offer gifts, which were usually cigarettes or coffee.

For most women and those men unable to afford transportation and burial at Najaf, the only alternative was a small cemetery on the village outskirts. Although some locally buried bodies were bedecked with mud imitations of the jewelry they wore in life, this never occurred, to my knowledge, with the bodies sent to Najaf.

Local burials were quickly made in the 1960s, and those family members lucky enough to have a job soon returned to their daily activities. One of our pot washers, a lad about 9 years old, asked one day if we would permit him to have an hour off. A few moments later I saw him with a small group of people on “cemetery hill.” He returned in about 45 minutes.

“Did someone in your family die?” I asked him.

“Oh yes,” he said, “my mother.”

“Is there anything I can do?” I asked. “Please take the day off. I’m so sorry.”

“Oh no,” he said. “That’s not necessary, God is good.”

He sat down before a pile of potsherds and went on with his work.

The Mi’dan

The Mi’dan, sometimes known as Marsh Arabs, depend on the watery environment of the marshes for their way of life. They keep water buffalo, which provide them with fuel and milk, and have even taught these semi-domesticated creatures how to forage beneath the water’s surface for succulent reed shoots and sedges.

Animals such as the water buffalo cannot really be considered domesticated if their owners fail to supervise their mating, and the Mi’dan did not consider this their business. Houses of the Mi’dan are built either in the marsh itself atop man-made islands of reed mats layered with mud or on the very edge of the marsh where they and their animals have easy access to the marsh vegetation. Both women and men are practiced at harvesting reeds and turning them into reed mats and baskets, which they sell or trade to itinerant trades people. Additional sustenance is derived from sowing rice during the spring in the seasonal marshland formed by the annual inundation. The most important source of outside income, however, comes from the making of reed mats and from the dairy products of their water buffalo. The Mi’dan fished for their own consumption but despised nets and thought that the only manly way to catch fish was to spear them.

Both the Bedouin and the Beni-Hasan looked down on the Mi’dan for keeping water buffalo, which both regarded as disgusting. Over the years serious scandals arose when the Bedouin or Beni-Hasan thought local butchers had substituted the meat of a water buffalo for the meat of domestic cattle. The Beni Hasan also thought that the Mi’dan were incomprehensibly silly to spend so much time trying to spear a few fish when they could catch many more with nets.

Aside from these distinctions and their different dwelling areas and subsistence modes, essential patterns of Mi’dan culture such as family organization, life-crisis ceremonies, division of labor, and notions of good and evil are very similar to those of the Beni-Hasan. One instantly noticeable difference is the custom of the Mi’dan women to go about their work without the abaya.

The architecture of the Beni Hasan and the Mi’dan, which was markedly different when the al-Hiba expedition began its work, grew more similar as time passed (see p. 100–101). Most members of the Mi’dan did not consider some so-called Mi’dan who lived in isolation or semi-isolation in the marshes as Mi’dan. These people often had been in some trouble with the law and had come south to lose themselves in the marshlands. On the surface, at least, their way of life was identical to that of the Mid’an, and they were held by their hosts to the same religious and moral standards of conduct. In the many years of our work in the area, I never heard of the smallest violation of conduct on the part of these outsiders. They were very dependent on the Mi’dan’s early warning system which effectively alerted everyone that an outsider was coming and usually identified the newcomer. At least an hour before the police could arrive at their homes, those in trouble with the law would melt into the marshes. It took me a long time to figure out how this was done, but it seems that signals were sent by a complicated system of gunshots, drums, and sometimes children’s whistles in a code based on the number of shots or notes and the time intervals between them.

The typical family has very few household possessions. They can, in a few short hours, roll up the reed mats which provide them shelter, put their few possessions into their boat or boats, and, driving their water buffalo before them disappear into the marshes, sometimes to isolated islands sometimes to hide in the water itself among the giant reeds.