One major way in which this translation differs from previous ones is treatment of the dash, which can be viewed in the context of domestication. In the typesetting, the dash was oftentimes replaced by a period, comma, or semicolon. This was done to an even greater degree when Costello translated from Persian to English. While in some instances a substitution (dash for another form) can be made without a change in the meaning of an individual sentence, we must keep in mind that Hedayat chose the dash over and over again, instead of these other, more common, forms of punctuation. The dash is different from the period, comma, and semicolon in that it has additional attributes: the dash can represent emotion, haste, or the breaking off of a thought.

The narrator of The Blind Owl is disturbed and one imagines him scribbling furiously away. One way in which Hedayat shows this emotion and haste is with the repetitive use of the dash. The narrator in Costello’s version is much calmer and under control, and I believe one reason is the elimination of the dashes brought on by the typesetting and translation.

Method of the Current Translation

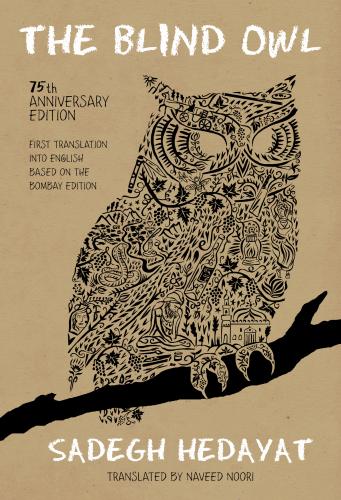

In this translation, I consciously sought to bring the English reader into the world of Boof-e koor. My method was to begin with a foreignized bias to preserve each sentence and its meaning. Next, repetitive proofreading and editing were undertaken to improve the flow and bring the text closer to the center. The result is the retention of untranslatable Persian words (with footnotes), the use of atypical English words and phrases to convey the Persian, and the use of the dash as it appears in the Bombay edition. Of course the danger with foreignization is that it challenges the reader to leave behind the confines of their familiar language and home to travel to a different land. In this edition I have tried to balance the two, while not fearing the effect of foreignization.

As noted above, I believe the use of the dash to be part of the discussion between domestication and foreignization in translation. In the Bombay edition, the narrator is more agitated, and I have tried to preserve this mood by means of the dashes. Although readers may initially be put off by this, I believe that, as with any particular form of punctuation that is used repetitively as a literary device, they will get used to it and that this effect will add to the experience, as it does in the Persian.

In other parts of this work I have tried to preserve the essence of Hedayat’s Blind Owl by using atypical English words or phrases. Kabood is a key word scattered throughout the text. Costello translated this word as “blue,” but this fails to convey its more complex meanings. In Persian this word can be defined as a color or a bruise, and in the context of the work it is closer to the latter. In the book Tavil-e Boof-e koor,1 there is an interesting discussion about the pairing of niloofar-e kabood. Strictly speaking, niloofar in Persian is a morning glory, while niloofar-e abi is a lotus. Hedayat apparently had translated the lotus flower from French into niloofar-e sefid or a “white” niloofar in Persian. This takes on additional significance because the lotus was a symbol of Achaemenid Persia seen in the bas reliefs at Parseh (Perspolis). By turning white (sefid) into dark (kabood), and coupling this with a symbol of ancient Iran, the “bruise” of kabood had particular importance for Hedayat. However, in terms of translation, the use of “lotus” for niloofar produces difficulties. Lotuses are water plants and we have clear references in the work to niloofars growing in dirt. While one can argue that certain parts of the work could be somewhat surreal in nature, the niloofars in dirt also occur in sections which are not surreal. I believe that the use of niloofar is complex, and that Hedayat likely had the lotus in mind as a symbol. For consistency, I have chosen “morning glory” for niloofar while making the reader aware of the additional symbolism.

One of the keys to understanding Hedayat and Hedayat’s Blind Owl is the relationship between pre-Islamic and Islamic Iran, the relevance of which has been lost in the two existing English translations. Part of this has to do with not setting off the second part of the book. Favoring fluency over meaning in translation of key words (domestication) has also contributed to this. As Ghiyasi has noted, the “bruised lotus” is an important symbol (which a “blue” flower could never convey). Likewise, I would like to point out the usage of pre-Islamic and Islamic coins in the two different sections signifying the two different time periods. In this translation I have tried to preserve this aspect, providing footnotes with explanations to serve as a starting point for the interested reader. For a detailed description and discussion of the symbols of the vase, the ethereal girl, city of Rey and the Suren River, and their relationship to Hedayat’s philosophy and his earlier work Parvin, Sassan’s Daughter, I refer the reader to Houra Yavari’s essay entitled “Sadegh Hedayat and a modernist view of history.”1 In addition, M. F. Farzaneh’s Ashnai ba Sadegh Hedayat provides details of Hedayat’s personal life that were used as inspiration for certain passages (the breaking of the vase, the numbers two and four, etc.), as well as an interpretation of The Blind Owl as Hedayat’s Manifesto.2

Translator’s Style and Conclusion

Beyond the theory and methods behind translation, each translator brings their own voice to a translation. Although some may try, as Venuti states, to remain “invisible,” in the act of choosing one word over another, over and over again, different styles and voices are inevitably revealed. And this provides another means of distinguishing various translations. Below is the first sentence of The Blind Owl translated by three different persons. In this first sentence alone we see three completely different results. Each of these translations reveals Boof-e koor in a different way. It is my hope that this and other translations of Hedayat’s works will spur a renewed interest in his works.

Costello: “There are sores which slowly erode the mind in solitude like a kind of canker.”

Bashiri: “In life there are certain sores that, like a canker, gnaw at the soul in solitude and diminish it.”

Noori: “In life there are wounds that, like leprosy, silently scrape at and consume the soul, in solitude—”

Naveed Noori

Samangan

2011

1 Dates are given first in the Gregorian calendar, followed by the Iranian calendar.

2 All references to the Bombay edition in this introduction are based on the following edition which is a reproduction of one of the original 50 mimeographed copies (in the possession of M. F. Farzaneh): S. Hedayat, Matn-e kamel-e Boof-e koor va Zende be goor [The complete Blind Owl and Buried Alive] (Spanga, Sweden: Nashr-e Baran, 1994).

1 H. Katouzian, Boof-e koor-e Hedayat [Hedayat’s Blind Owl] (Tehran: