5) Page 27 of the Amir Kabir edition corresponding to page 27 of the Bombay edition: Two words amad va in the Bombay changed to one word amade with a verb tense change in the Amir Kabir. There is also a change of a comma to a period here.

6) Page 30 of the Amir Kabir edition corresponding to page 31 in the Bombay edition. The insertion of the period after boodam in the Amir Kabir edition cuts the sentence midstream. This has the effect that the new sentence, starting with hala, changes the narration from the past abruptly to the present tense, which is incongruous with the rest of the first part.

In addition to the changes noted above, all Persian editions and major translations (including Lescot’s) do not set off the second part of the story in italics. In the Bombay edition, every paragraph in the second section is set off with quotation marks, signifying a narrative within a narrative. This important omission clearly can affect the entire way in which The Blind Owl is interpreted, and may be one reason for the disparate analyses of the work.1 Below is an example of how Hedayat set off this part (see arrows).

The various changes noted above can be traced through the various translations and editions. One easy way to tell this is by examining the first sentence of the book. In the Amir Kabir and Javidan editions, as well as Costello’s translation, this sentence is an entire paragraph (that is a new paragraph starts with the next sentence). However, in the Bombay edition and Lescot’s translation, the first sentence is part of a much longer paragraph.

Other formatting changes like this one can be easily compared between the editions. From this alone it is clear that neither Costello nor Bashiri used the Bombay edition for their English translations, but used an edition derived from the Amir Kabir editions (post third/fourth).

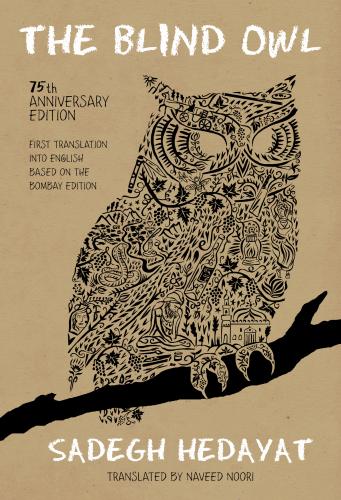

The Bombay Edition as the Definitive Edition

While some of the individual points I have made above (such as the changing verb tenses) could be argued as the author’s wishes, the main difference in the texts is the preponderance of extremely minute changes, such as single punctuation or letter changes within words to form a different tense or different word. This is suggestive of typesetting errors rather than artistic decisions by Hedayat. Some of these changes clearly have a negative impact on the text and affect the flow, and perhaps are one reason Hedayat’s writing style has been faulted by some.

One possibility that I can not exclude is that Hedayat could have made some of these minor changes and handed it over to the typesetter who introduced a series of errors. However, as noted above, there is no evidence that Hedayat ever revised The Blind Owl after the Bombay edition.

Finally, this case is very similar to Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The House of the Seven Gables.1 In examining the manuscript and first printed edition Bowers writes:

When an author’s manuscript is preserved, this has paramount authority, of course. Yet the fallacy is still maintained that since the first edition was proofread by the author, it must represent his final intentions and hence should be chosen as copy-text. Practical experience shows the contrary. When one collates the manuscript of The House of the Seven Gables against the first printed edition, one finds an average of ten to fifteen differences per page between the manuscript and the print, many of them consistent alterations from the manuscript system of punctuation, capitalization, spelling, and word-division. It would be ridiculous to argue that Hawthorne made approximately three to four thousand small changes in proof, and then wrote the manuscript of The Blithedale Romance according to the same system as the manuscript of the Seven Gables, a system that he had rejected in proof.

A close study of the several thousand variants in Seven Gables demonstrates that almost every one can be attributed to the printer. That Hawthorne passed them in proof is indisputable, but that they differ from what he wrote in the manuscript and manifestly preferred is also indisputable. Thus the editor must choose the manuscript as his major authority. . . .

In summary, as of today, we only have two main versions, the Bombay which we know was Hedayat’s as it is handwritten and the later texts, which upon close examination were found to have many inaccuracies. For the reasons stated above, the Bombay edition should be considered the definitive version. This view is also shared by Hedayat scholar M. F. Farzaneh as well as the Hedayat Foundation, both of whom have published the Bombay edition for this reason.1,2

Domestication versus Foreignization in Translation

Because of inherent differences between languages (meanings of words, sentence structure, etc.) a literary translation can never duplicate the original; however, it is the translator’s task to strive for this. Translators constantly wage war and peace between fluency and fidelity, where the former represents the ease of reading (or “flow”) in the target language, whereas the latter represents the accuracy in conveying the author’s meaning from the source language.

Schleiermacher and Venuti have argued against the centuries-old tradition of emphasis on fluency.3 They present this within the context of domestication versus foreignization of translation. Domestication occurs when fluency is strived for at all costs, and the culture, words, and even meaning of the text are made to conform to the target language (the analogy is that the work travels to the source country and assimilates or is domesticated). Foreignization is the opposite, where an effort is made to preserve the source language and culture by use of language or techniques that may be unfamiliar to the reader (in this case it is the reader that travels to a foreign land to experience the work). Venuti writes:

A translated text, whether prose or poetry, fiction or nonfiction, is judged acceptable by most publishers, reviewers, and readers when it reads fluently, when the absence of any linguistic or stylistic peculiarities makes it seem transparent, giving the appearance that it reflects the foreign writer’s personality or intention or the essential meaning of the foreign text—the appearance, in other words, that the translation is not in fact a translation, but the “original”. . . . By producing the illusion of transparency, a fluent translation masquerades as true semantic equivalence when it in fact inscribes the foreign text with a partial interpretation, partial to English-language values, reducing if not simply excluding the very difference that translation is called on to convey.

Domestication of the Blind Owl

As the Costello version is the most popular, widely available, and considered the gold standard, I will focus this discussion mostly on this work. Costello’s translation is entirely fluent and reads well; however, in doing so, the narrator’s voice has changed, and the text has become domesticated. This was one of the main reasons I decided to undertake this project. There are many instances where the subtleties of Hedayat’s written word have been overlooked for ease of transitions. Below I will cite a few examples of this.

On page 11 of the Bombay edition Hedayat writes, “hameye mardom be biroone shahr hojoom avorde boodand.” Costello has translated this as “Everyone had gone out to the country.” While this is correct translation in terms of the action, it only manages to push the narrative from Point A to Point B. By ignoring the verb “hojoom avordan,” Costello