The Master took one quick look at Robbin Tress. “I think not, Gerald,” he said slowly. “We will have to catch up later—of course you will provide. But Robbin should be home.”

The girl was absolutely crestfallen. She was actually wringing her hands, something I don’t seem to see much. “I’m so sorry, Sir,” she told me earnestly. “But it is a strain, and they tell me I have to be careful about strain. In a little while when I’m better, I won’t have to be so careful maybe, but right now I do, Sir, and I am sorry but I think I do have to go home, if Master Higsbee will help me get there.”

She did have enough spirit left, or something, to bat her eyelids at the Master a little, and stifle a small giggle. To his credit, he let both pass as friends, not even asking for recognition codes.

“Of course,” I said. “I’ll check in with one of you as soon as I can, and as soon as I know anything. But let’s shut up shop in a hurry—I’d like to get there while the scene is still a scene.”

The Master nodded. Robbin was still agreeing we should hurry when he bundled her into their waiting closed car and took off, and by that time I was flagging a passing taxi and giving him directions to VT.

Which was, of course, the name of Ramsay Leake’s modest estate—Leake being a computer-simulations expert. If you don’t recognize the allusion, that’s because it is rather a Classical tag; back before the Clean Slate War, computer people on early comm networks used to speak of RT and VT—Real Time, or life every day, everywhere, and Virtual Time, or life on the comm net. The differences were beginning to be appreciated, apparently, right from the start of comm networking, and Leake had reached back to the ancients for his estate name, as a neat enough challenge to those differences, and one I found instantly admirable. Unfortunately, I couldn’t compliment him on it, not any more.

He was right there—what was left of him. But there wasn’t enough left to compliment—after a ten-story fall, there was barely enough left to recognize. Ravenal has 0.97 Standard gravity, but the 0.03 difference didn’t seem to amount to much in practical terms just then; Leake was just as jellied by the impact as he’d have been if he’d come down somewhere in ancient Oregon, or Uta.

VT had been a ten-story tower, round and rather thin, sticking straight up and surrounded by terrace-railings every two stories from the fourth on up. The word that sprang to mind, out of ancient literature, was “minaret”. A fascinating building, and about one hundred times as imaginative as your average Ravenal structure of any sort at all. Oh, why not—a thousand times. Easily.

B’russ’r was there, too, some distance from the minaret, chatting politely with a police official I’d met briefly, a Detective-Major Hyman Gross. I climbed out of my taxi and ambled over to join them, perhaps thirty feet from the body, where a small army of techs was at work taking photographs, measurements, readings and anything else not nailed down. As I came within earshot, Gross was saying: “I respect your abilities. Hell, anybody respects your abilities, Mr. B’dige. But this isn’t even a large coincidence. Sort of thing that happens all the damn time, I mean to say.”

B’russ’r only nodded at the man patiently.

“It is not the coincidence of the weapon that concerns me,” he said. “It is the coincidence of the occupation—not, I think you will agree, a small matter. My conclusion is a consequence—”

“Of information upload, I know,” I said. “Hello, B’russ’r. Major Gross.”

The Major gave me a stare. For Gross, this was a large undertaking: he had a red round face, even redder up where most of his hair had once been, and big, big eyes that bugged out as far as I’ve ever seen a human being’s. He focused those exopthalmic things on me and said: “You too, Knave? What is this now, a plot? Are you ganging up on me now?” in a wheezy, wine-soaked little baritone.

“Perhaps Knave appreciates the situation,” B’russ’r said.

“I might,” I put in, “if I knew what it was. Leake fell from his tenth-floor balcony. How in the name of the original preSpace Gross do you know he was shot first? The shape he’s in, that ought to take a careful autopsy.”

“The shot was seen and heard,” B’russ’r said. “This time, we have witnesses.”

Gross snorted. “What do you mean, this time?” he said. “If you truly want to tie this death here to the Berigot shootings five years ago, you had a job lot of witnesses then. We all of us did.”

B’russ’r stirred his wings a bit, forth and back. Confusion, and enlightenment—the Berigot equivalent of Aha. “I see,” he said. “There has been a misunderstanding. It is not the shootings I wish to connect, Major Gross. It is the theft.”

“Theft?” Gross said. “And just by the way, Knave, who the Hell is this ‘original preSpace Gross’? Relative of yours? Some long-forgot relative of mine, perhaps?”

B’russ’r nodded a little sidewise at me, and I shrugged. Translated: “Do you mind if I supply the data?” “Not at all, go right ahead.” Berigot are very polite, even a tad ritualistic, about information transfer. Naturally, I suppose.

“The Gross referred to,” he told the Major, “is the author of Modern Criminal Investigation, a much-used police textbook just preSpace. Not only historically noted, but at times still quite helpful; his differentiation of some burned corpses from fight victims remains classic.” He bowed just a trifle. “Not perhaps a subject of study in today’s academies,” he said. “As for the theft—”

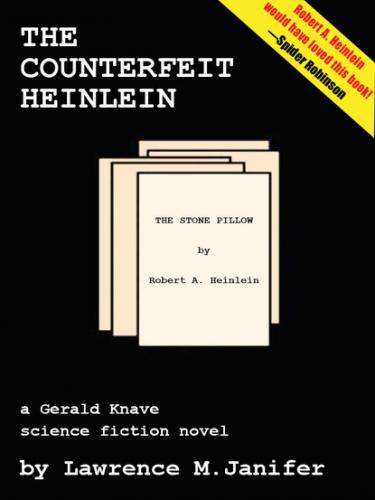

He went on to describe, very sketchily, the Heinlein-forgery situation. Gross nodded. “And you believe this death here is connected?” he said at last. “Why? What would connect this Leake with an old manuscript?”

“Leake,” B’russ’r said, “would have helped to fake it. The conclusion is, if not certain, surely irresistible.”

Gross said: “Why would you say irresistible? Why would you come to any conclusion at all, for heaven’s sake? Look, Mr. B’dige, you mention occupations. Well, this Leake was a computer-simulations expert. Whatever your old manuscript might be, it wasn’t a computer simulation. When it was written new, perhaps there were people who didn’t even have computers.”

B’russ’r cleared his throat—something a Beri never does, except to imitate humans. I’d been wondering when he’d get around to it, and now he had. “B’russ’r, please,” he told Gross. “It is true that B’dige is a name. But like most names placed in second position, for Berigot, it is functional, not personal. Simply B’russ’r, please.”

“Not personal?” Gross said.

I nodded sidewise at B’russ’r, and he shrugged back at me. “That second name,” I told Gross, “is a little bit like ‘Teacher,’ say, or ‘Driver’—and a little bit like ‘redhead’ or ‘shorty.’ It describes a function or an attribute of some sort, not a person. The name a Beri uses is his name—the first part. The second part is more of a title, or a nickname—at nay rate, functional, not personal.”

Gross nodded. I have no idea to this day whether he’d got it. But he did say: “Good for it, then: B’russ’r. All right with you?” and B’russ’r nodded very politely.

“Thank you,” he said. “And as for your question—the manuscript was, in a way, a computer simulation. Such a simulation must have been used to create the effect of the forgery; at the detailed level at which it was constructed, there would be no other way.”

I’d had the taxi ride over to think that out, and of course it made sense. Gross hadn’t had either my additional minutes, or B’russ’r’s information upload, and just looked confused.

“Some of the isotope assay checked out,” I said. “And how do you build a pile of paper, and a barrel of ink, that has an isotope percentage match to, say, 1950 instead of 2300? You do it by running the entire molecular makeup through computer simulation, tracking it