I stared at the phone. “Do you do that now?” I said.

“Sometimes,” Robbin said. “For people I know a long time. The Master would have to come too, though, if you don’t mind, Sir.”

I nodded, and then said: “Fine. When?”

“An hour and a half, Sir?” she said. “I will call him, and then wait for him here.”

Robbin had improved out of all belief. “An hour and a half,” I said, and began to give her directions.

“Oh, Sir, don’t bother about that, please don’t trouble yourself,” the breathless voice said. “The Master will know, he’ll take me. Closed car, Sir, I really have done it before.”

“Fine,” I said. “I’ll see you both then.”

“Goodbye, Sir,” Robbin said, “and thank you so much again for thinking of me.”

Finished. It might be that the Master’s way of ending a phone talk had a point. I said goodbye politely, put the phone away and thought about refreshments. Coffee of course. And—

I had time for one fairly speedy shopping trip. Nobody shot at me.

CHAPTER SIX

And thirty-five minutes after I came back weary and heavy laden, as the Bible says, there they were, actually sitting in my living-room. The Master took his coffee black. Robbin Tress took hers with cream and sugar, as I did, and if something as small as that could have made me doubt the habits of a lifetime, little Robbin’s taste in coffee would have. I’d settled on a sort of local fruit-cake, sticks of hard cinnamon bread, a few cheeses, and some fruit, which turned out to be a mistake: plums, from what were advertised as actual descendants of actual Earth plum trees. They might have been—who am I to argue with advertising?—but if so, a great deal had happened to the family in the intervening centuries, all of it terrible.

Robbin was delighted by the exotic plums, which didn’t make up for the look that crossed Master Higsbee’s face when he bit into one. But the cake was good, the cheeses acceptable, and the coffee Indigo Hill, the emperor of coffees, from my own stock. And the talk rapidly became helpful.

“The first question, of course,” the Master said while refilling his cup, “was why the forgery had not been detected earlier. This is, after all, Ravenal. These people can be expected to know their business, and indeed they usually do. One notes the occasional exception, but one does not note many.”

“Maybe it just cost too much to find out,” Robbin said dreamily. I remembered just in time not to object, or to wonder where she’d gotten such a notion from. “Dreamily” was the key, of course; Robbin in that sort of tone was being Robbin.

A long time ago, back when there was real science-fiction, there was also a place called Boston, which was supposed to be stiff with tradition of several sorts. Maybe it was—at this distance how can anybody tell tradition from random habit? At any rate, the traditional Boston ladies, if that’s what they were, wore some perfectly terrible traditional Boston hats, and one day (according to an old story) somebody asked one such lady where she got her hats.

“In Boston,” she said, “we do not get our hats. We have our hats.”

Robbin did not get her ideas. She had her ideas. I had once described my two guests to an interested lovely to whom I was spinning a tale, and hoping for Othello’s satisfactions, if you remember (and there is no good reason why you should): if my lovely would only love me for the dangers I had passed, I was more than willing to love her in return, for she did pity them. Master Higsbee (I told the lovely, who was indeed fascinated, and if not wholly loving toward me, certainly in frenzied like) knew everything that could possibly be known. (That was perhaps just a touch exaggerated. Not really very much.) Robbin Tress knew the things that couldn’t possibly be known.

The people on Cub IV, where she’d been born and, so far as the phrase was applicable, brought up, looked on her as a sort of wild psi talent, and on Cub IV, where there’d been a history of difficulty—open damned warfare, in fact—with psi talents among non-humans, this did not make her popular. How much of little Robbin’s personality was originally built in by manufacturer, and how much was the result of social strain—to put it very, very mildly—during her childhood and teener years, nobody may ever know, though small dedicated crews on Ravenal do keep trying to find out. What she has doesn’t seem to be psi, exactly—it doesn’t follow any of the normal rules for such things, even where there are any rules. Robbin doesn’t seem to know anything she isn’t asked about, or somehow prodded by interest into thinking of. And she doesn’t reach the answer by any process anybody has ever been able to understand; the answer isn’t reached at all; it is simply going to be there. As closely as anybody has ever been able to see, if you don’t ask the question (or otherwise engage her interest), the knowledge isn’t going to be there; if you do, it is. Maybe.

When word of Robbin got to Ravenal (as word of most oddities does seem to, sooner or later) a state of fascination ensued, and after a little backing and filling (and not very much) Robbin had a new home, and many new friends. People who did, in fact, actually like her, and did their level best every minute not only to solve the set of very frustrating puzzles she presented, but to help her.

Which was why Robbin Tress was on Ravenal when I needed her.

Master Higsbee was on Ravenal, of course, because where else would a man who knew everything knowable be?

And both, as I say, were being helpful. Master Higsbee nodded when Robbin mentioned the high cost of finding out about the forgery, and told me:

“In fact that was the reason, Gerald. The normal tests were run. Isotope assay was conducted on the paper and the ink for carbon-14, and for some quicker decay isotopes. A full run on all checkable isotopes simply represented too much of an expense on a very, very slight chance.”

“The chance being that somebody had figured out a way to beat some isotope patterns, but not others,” I said. The Master gave me a faint nod. I was doing well.

“Exactly,” he said. “As far as was known, isotope assay was infallible even in limited form. Why, then, not simply agree that assaying some distributions would be enough?”

“And it wasn’t,” I said.

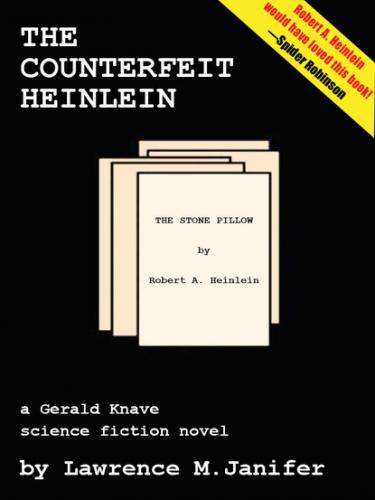

“A friend of yours, Gerald, is a great admirer of Heinlein. He is also a thorough man, and it worried him that a thorough job had not been done. He contributed his own funds, in part, for a full assay, persuading First Files Building to pay the remainder. And the forgery became obvious.”

“A friend?” I said.

I have never heard anybody give Mac’s name the way the Master did. “Charles MacDougal,” he said. Apparently he really is immune to a lot of normal human itches.

It’s a name most people want to shake full out, like a flag: Charles Hutson Bellemand MacDougal, B. S., M. S., Ph. D., this, that, and the other, full Professor of Molar and Molecular Physics, Ravenal Scholarte, a holder of two Nobels and, I am happy to admit, an old friend. I’ve heard people say C. H. B. MacDougal, and I’ve heard a lot say Mac. But Charles MacDougal was a first that night, and has remained an only. In fact it took me about two seconds to figure out who the Hell the Master was talking about—I was as dislocated as I’d once been when a Professor of Ancient Literature, years ago in my boyhood, mentioned Francis Fitzgerald instead of F. Scott.

“Mac was involved in this?”

“‘Mac’ was the cause of the forgery’s being discovered,” he told me testily. A little testily. “In fact, I have now said that twice.”

Robbin said suddenly, and dreamily, breaking the Master’s irritated mood: “They counted all the isotopes, and some of the numbers didn’t add up right.” Which is an inelegant sort of way of describing what had certainly happened.

The ancients knew about isotope assay, in