The Future History—well, there were a lot of these, though Heinlein’s may have been the first, not only before the Clean Slate War but before World War II, which takes us all the way into antiquity. None were accurate, but accuracy was never the point—the point was to create a framework to put stories in, so that the stories meant a little more all together than they could one at a time. World-building, which is what a lot of science-fiction seems to have been, takes place in three dimensions of space and one of time, and Future Histories use up the time dimension most thoroughly.

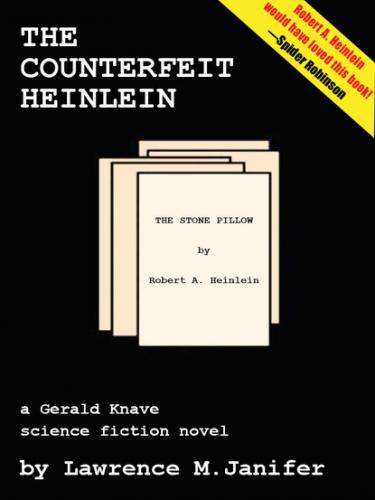

In Heinlein’s, there was a period in which the United States, his model for society, fell into a dark age, under the rule of a religious crank called the Prophet, Nehemiah Scudder. The Stone Pillow was supposed to tell the story of some of the rebels and martyrs fighting Scudder and his successors, and that was all anybody knew about it until Norman’s little keepsake turned up.

It turned out to be the story of Duncan BenDurrell, a convert to the fighting faith of Diaspora Judaism and second-in-command of a religio-political rebel army fighting the current Prophet, third of that title, in a wild and uncitified area of what was, in Heinlein’s own time, Oregon.

* * * *

It was at that point, as I was spinning all this out for little Robbin Tress, that the Master interrupted me.

“You have never actually seen the manuscript you speak of, have you, Gerald?” he said in that rasp of his.

I shook my head.

“Let me, then, recite a brief passage,” he said. “It was really a remarkable forgery, in its way—this will show you why, very briefly. Quite typical of early-middle Heinlein, and quite persuasive.”

Robbin was sitting wide-eyed, one bite of cake held forgotten between two fingers. I felt that way myself—forgery or not, I felt as if I were going to get a quick glimpse of a Heinlein story I had never read before. I had to remind myself to start breathing again, at least long enough to say: “Sure. Go ahead.”

Even Master Higsbee’s rasp of a voice couldn’t spoil the effects. I’ll give it to you straight, though—the way it would have looked in print, starting (I checked, much later) with page 94 of the manuscript.

* * * *

94

believe a word of it. But he frowned angrily, and he thought he looked fairly convincing doing it. He owed that much to the Dias, and he delivered it.

“That may be so,” Joshua said. “But whatever you think of him, you must admit Duncan has been acting suspiciously.”

“I’ll admit no such thing,” Frad said. “Duncan BenDurrell may not be an honorable man—as you and I understand honor, Excellency—but that’s no cause for suspicion. The Prophet Himself tells us that there are not sufficient honorable men in an entire city to save it from destruction, though only ten be needed. Discourses, 3:13.”

Joshua stirred uneasily, swinging a leg as he shifted a little on the rickety Judgment Seat. “I say BenDurrell—and the name alone stinks in an honest man’s nose—is in league with destruction, friend Frad. And I say destruction should be his portion, as the Prophet suggests for unbelievers—Originations 4:10.”

Outside the Summer Palace, a group of celebrators began to shout songs and hymns as they wove drunkenly past. Frad felt it wise to throw a glance of irritation at the open window, and Joshua shook his head and clucked disapproval.

“Such displays should be coventried,” he said, and Frad shook his own head. It was possible, he knew, safely to disagree on such a point.

“Do not attempt to be more pious than the Prophet himself requires,” he said. “It is said that all men need at times to unbend—Discourses 2:2—and who are we to judge their lives? BenDurrell is of an unfortunate heritage, Excellency, but that is all that can reasonably be said against him.”

“We are appointed to judge,” Joshua said mildly.

“So? Who was it made the appointment, Excellency?”

Joshua smiled. “God has made it,” he said serenely. “God, through His First Prophet and through that Prophet’s successors. What would you, then?”

“I will not pick a quarrel with Him,” Frad said, “nor His First Prophet, nor that First Prophet’s successors either. But it has never been clear to me that the proof of such an assertion is beyond any cavil.”

“Then search yourself until you find that clarity,” Joshua said, and a hint of sternness came into his voice. “You sail too close to the wind of heresy, Frad Golden.”

Frad shrugged. “It’s of no importance,” he said. “But, in these difficult times, we must avoid even the appearance of injustice.”

Joshua stirred a little on the Judgment Seat. “No one will worry about appearances, Frad Golden,” he said. “BenDurrell is nothing, less than nothing. No one will bother himself over one man’s fate.”

“But BenDurrell is just that, Excellency,” Frad said, as gently as possible. Joshua might listen to reason—the possibility existed—but it would not do to anger him. Duncan would not be well served by the casting-out or imprisonment of Frad Golden.

“‘Just that’? He is nothing, and less than nothing.”

“He is one man, Excellency, as you have said,” Frad went on. “And like every man, he is the one for whom the First Prophet came, as He Himself said—Generations 7:33. He is the one for whom sacrifices were made, in the days of the beginning. We are taught that every man has such value that he, alone, might be the cause of all the work of the First Prophet, and all the mercies of God Himself. One man, Lord—as valuable as any one man in all this world. As valuable, one might say—so we are taught, an you read it aright—as the Prophet himself.”

CHAPTER NINE

When the Master’s rasp stopped, the place was very quiet. Little Robbin Tress whispered: “Wow. Gee, Master Higsbee—gee, Sir—wow, I wish it were real. I mean I wish it were a real Heinlein story.” And then, dreamily: “Maybe, someplace, it is.”

“It might be so,” the Master said. His voice sounded tired, but no more tired than usual. If asked, he’d have told you, extensively, how worn and ancient he was, and how much the recital had taken out of him. So I didn’t ask.

Robbin offered to help with cleaning up, but the Master knew how I feel about household chores generally and dishwashing in particular, and managed to persuade her that my refusal was serious, and not ill-tempered in the least. We spent a few minutes in reminiscence—Robbin had once been a help about a Fairy Godfrog, of all the damned things, and the Master remembered some odd consulting he’d done for me here and there (and all the reasons why I shouldn’t have had to consult him, but could very well have figured matters out on my own)—and then, with both parties readying graceful goodbyes, it happened again.

This time, the damn nuisance didn’t miss.

Of course, this time he wasn’t shooting at me. In fact, we none of us heard the shot, for which I was and am profoundly grateful; that one sound would have tossed Robbin back five years and more in her own progress, and, which seemed almost as important somehow, would have been the occasion for endless complaining from Master Higsbee.

Six or seven minutes later, we were finishing up goodbye-and-reply routines, of which Robbin had a full set (the Master’s version was of course short and simple) when my phone blipped, and they stood frozen at the door, the way people will, while I went and answered it.

B’russ’r B’dige’s sweet high tenor asked me if I were me, and on getting confirmation gave me the news. I said I would be right the Hell there, hung up, and began to shoo