[print edition page xxvii]

did not accept them; he was the first to laugh at a risky or foolish conjecture he had made the night before, and when he communicated with me, he found it good that I laughed my head off at it.”1

ETIENNE NOËL DAMILAVILLE, 1723–68 (3 articles). He was born, it seems, in a Norman village. His brother was a noble controller of the vingtième (5 percent) tax, but the rest of his family life is obscure. He received an uneven education before joining the army during the War of the Austrian Succession as a member of the king’s elite cavalry (the gardes du corps). Afterward followed a stint as a lawyer in Paris, leading to a position with the controller-general of finance. By 1755 he was a high official (premier commis) administering the vingtième tax himself, giving him insight into the subject of the long article that concludes our volume.

Around 1760 he came to know both Diderot and Voltaire and used his government position to advance their interests—distributing their illegal works, arranging mail service, supplying them with information. Both philosophes came to regard his talents highly. Voltaire called him a “soul of bronze—equally tender and solid for his friends,” and he became a trusted member of Diderot’s social circle. With d’Alembert gone by that time, moreover, Damilaville’s eager contributions to the Encyclopédie, both as writer and as editorial collaborator, were most welcome. On the other hand, d’Holbach, referring to some of his more speculative opinions, called him “philosophy’s flycatcher,” and Grimm saw him as dyspeptic and socially awkward. He had a reputation for religious heterodoxy, which may have affected his career advancement. For example, he was said to have attempted to convert Voltaire to atheism. Aside from his two long and important articles for the dictionary, Damilaville wrote little, though he was apparently preparing to do more writing when he retired in 1768, shortly before falling ill and dying at the age of forty-five.

ALEXANDRE DELEYRE, 1726–97 (2 articles). Born in Portets, near Bordeaux, into a longtime local family of merchants and professionals, Deleyre entered the Jesuit order at age fourteen, failed to find contentment,

[print edition page xxviii]

and left both the order and his faith at age twenty-two. After legal studies, he pursued a literary career with the help of his fellow Bordelais Montesquieu, moving to Paris in 1750, where he met Rousseau and, through him, Diderot and d’Alembert. In the 1750s, he edited anthologies of the works of Francis Bacon and of Montesquieu and contributed anonymously to a running polemic against the anti-Encyclopedist journalist Elie Fréron. He then pursued work in journalism, first with the Journal étranger (as editor), after with the Journal encyclopédique and the Supplément aux journaux des savants et de Trévoux—all of them open to religious and political reform.

He left journalism in 1760 and spent eight years as a tutor to the prince of Parma, where his supervisor was Etienne de Bonnot, abbé de Condillac. The latter rejected the English history textbook that he had asked Deleyre to prepare, because of its excessively favorable treatment of Cromwell. Returning to Paris in 1768, Deleyre wrote a work on northern European geography and exploration and contributed most of volume 7, book 19, of abbé Raynal’s History of the two Indies (1774). In that work, he defended a flexible approach toward political regimes with a marked preference for English limited government. In a 1772 will, moreover, he wrote that “France … has fallen because of moral corruption under the yoke of despotism.”

During the Revolution, he was the mayor of Portets for a time and helped draft the cahier for the Third Estate at the electoral assembly of the Bordeaux region. He was elected to the Convention from the Gironde in 1792 and voted for the king’s execution in January 1793. Educational reform was his most frequent area of interest. When the Convention was assaulted by rioters on March 20, 1795, he reportedly said, “I am a representative of the people, I must die at my post.”

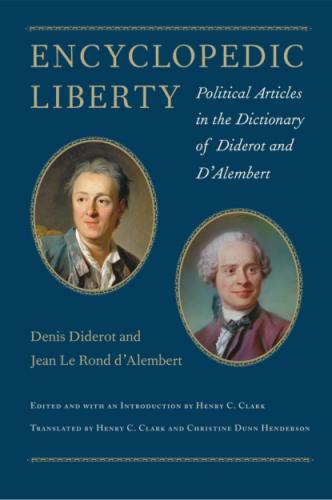

DENIS DIDEROT, 1713–84 (5,394 articles). Born in Langres, in eastern France, into a cutler’s family, Diderot at first took his religion very seriously, attending perhaps both a Jansenist and a Jesuit secondary school in Paris. When a religious life did not work out, he drifted toward a bohemian life of letters in Paris. In the 1740s, he lived mainly by translating several works, the most important of which was the Earl of Shaftesbury’s Inquiry Concerning Virtue and Merit (1745), a seminal work of sentimentalist

[print edition page xxix]

moral theory cited several times in the present collection. By this time, he had developed a heterodox philosophy that included elements of fatalism, materialism, and at least deism if not atheism. One of his works, Letter on the Blind (1749), earned him a stay in the prison at Vincennes, where he was famously visited by Rousseau.2 His selection as the editor of the Encyclopédie in 1747, which brought an end to his near-poverty, probably grew out of his previous associations with the publishers in his translation work.

Diderot quickly became the driving force behind the project as writer, editor, propagandist, and recruiter of collaborators. There formed around him a whole social network that contemporaries called the “encyclopedic party,” and that helped make the Encyclopédie unique among eighteenth-century reference works. Also unique was the extensive interest shown by Diderot and his collaborators in the world of the arts and trades, reflected in the eleven volumes of plates that appeared from 1761 to 1772, as well as in some of the articles on economic policy anthologized here.

In between his editorial duties, Diderot wrote voluminously, including plays in a new tradition of drame bourgeois or “bourgeois drama” that he promoted—Le Fils naturel [The natural son] (1757) and Le Père de famille [The father of the family] (1758); regular art criticism in Les Salons for Grimm’s journal Correspondance littéraire starting around 1760; and numerous works that he chose not to publish in his lifetime, three of which have done the most to secure his later reputation as a writer, namely, Rameau’s Nephew (begun in 1761), D’Alembert’s Dream (1769), and Supplement to the voyage of Bougainville (1772). He received a pension from the Russian Empress Catherine II the Great, who bought his library in 1765. He supported the Physiocrats for a long time but sided with Galiani in the latter’s polemic with them in 1769 and afterward.

After the last plates for the Encyclopédie were published in 1772, Diderot traveled in 1773 to Russia, where he advised Empress Catherine on her new reform program. “There is no true sovereign except the nation,” he wrote; “there can be no true legislator except the people.” Catherine

[print edition page xxx]

was unhappy and may have destroyed her copy of the work.3 During the American Revolution, Diderot supported the colonists. It is as difficult to summarize Diderot’s political views as it is that of the dictionary that he edited, partly because his public statements were clearly affected by the experience of imprisonment and by his running tension with French religious and political authorities. These problems are both reflected and generated by important articles of his such as POLITICAL AUTHORITY and NATURAL RIGHT in this volume.

JOACHIM FAIGUET DE VILLENEUVE, 1703–80? (15 articles). Not much is known about his early life except that he hailed from a Breton family of businessmen and was himself a pig merchant in Paris for a period of time. In 1748 he was director of a boarding school in Paris, and in 1756 he bought a government office as treasurer in the finance bureau in Châlons, a position that offered the prospect of nobility. It is not clear how he came to write for the Encyclopédie; he does not appear to have been a friend of either Diderot or d’Alembert. It would seem that his collaboration ended with the government’s suppression of the project in early 1759, since his last article, USURY, although appearing in 1765, was composed in 1758.

In the following decade, he took his writing interests to a different arena, writing the following five books: Discours d’un bon citoyen sur les moyens de multiplier les forces de l’Etat et d’augmenter