Rousseau, for his part, is relatively and perhaps surprisingly unimportant for understanding the Encyclopédie. His long entry ECONOMIE OU ŒCONOMIE in volume 5, widely available today as Discourse on Political Economy and not reproduced in this volume, was an early forerunner of his more developed political theory. And his signature concept of the “general will” is used in Diderot’s NATURAL RIGHT, Saint-Lambert’s LEGISLATOR, and Damilaville’s FIVE PERCENT TAX, which do appear in this volume, and occasionally in entries that do not, for example, GRECS (PHILOSOPHIE DES) [Greek Philosophy] and VERTU [Virtue]. D’Alembert does defend the dictionary against Rousseau’s two discourses of 1750 and 1754, with their indictment of the corrupting influences of the modern arts and sciences on human mores.9 But the Social Contract, Rousseau’s main political work, did not appear until 1762 and finds little echo in these pages.

Even more conspicuous by his nearly complete absence is Bishop Bossuet (1627–1704), the leading exponent of the political theory of divine-right absolute monarchy under the reign of Louis XIV.10 Nothing could more vividly illustrate the sea change in political thinking that had taken place between 1680 and 1750.

On the other side of the Atlantic, Americans did not know much about this most seminal of reference works. Unlike Montesquieu’s Spirit of the

[print edition page xxiii]

Laws, the works of Diderot and d’Alembert, including their great dictionary itself, were not widely disseminated in the American colonies. Neither the New York book lists nor the magazines and newspapers of the period mentioned Diderot frequently, nor were his writings widely available here—and those of d’Alembert even less.11 It would appear that Diderot was mainly known for his creative literature, that this was seen as having an irreligious tendency, and that the rest of his corpus was judged in this light. Not surprisingly, then, Americans tended later on to lump him with the regicides and atheists of the radical French Revolution, sometimes along with Rousseau and Voltaire, as Timothy Dwight, President of Yale College, did in a 1798 sermon.

Again unlike The Spirit of the Laws, the Encyclopédie was never translated into English in the eighteenth century, although a number of attempts were announced by the book publishers.12 That it was quite expensive would also have put a damper upon its distribution. On the other hand, Franklin, Adams, Jefferson, Madison, John Randolph, and William Short were among those who owned copies, and it was available in at least some institutional libraries of the time. Hamilton cited the article EMPIRE in Federalist No. 22.13

The English-speaking world’s engagement with the Encyclopédie was slight in the nineteenth century and not much fuller in the twentieth. To my knowledge, there have been only two anthologies of articles translated into English since 1900: Nelly S. Hoyt and Thomas Cassirer’s Encyclopedia: Selections and Stephen J. Gendzier’s Denis Diderot’s The Encyclopedia: Selections. Of the eighty-one articles in the present volume, thirteen have appeared (in whole or in part) in these previous collections. There are also a few political articles to be found in the first thirty pages or so of John Hope Mason and Robert Wokler’s Political Writings.14

[print edition page xxiv]

French-language anthologies of political writings include Diderot: Textes politiques, Diderot: Œuvres politiques, and Politique, volume 3 of Diderot, Œuvres, edited by Yves Benot, Paul Vernière, and Laurent Versini, respectively. John Lough’s Encyclopédie of Diderot and D’Alembert is a French-language compendium that includes several political entries.15

Starting in the late 1990s, a major collaborative effort centered at the University of Michigan aimed to make available on the worldwide web an English translation of as many articles as the sponsors could find translators for.16 This project, undertaken in the capaciously collegial spirit of the original eighteenth-century enterprise, is an inspiration to the world of teaching and scholarship. But perforce, the Michigan Collaborative Translation Project does not have the present volume’s focused sense of purpose.

The present volume is therefore unique. It provides a wide-angle window onto virtually every aspect of the political thought and political imagination of the most ambitious collaborative enterprise of the eighteenth century. There is iconography, biography, and history. There are philosophical reflections and topical interventions. There is broad constitutional analysis as well as detailed coverage of legal, economic, and administrative affairs. Religion, morality, family, and sexuality on the one hand, and war, slavery, and fiscality on the other, all come in for treatment of some sort in the present collection. In short, the full sweep of what it meant to think about politics in the eighteenth century is represented here in as eclectic, open-ended, and capacious a manner as was feasible between the covers of a single volume.

[print edition page xxv]

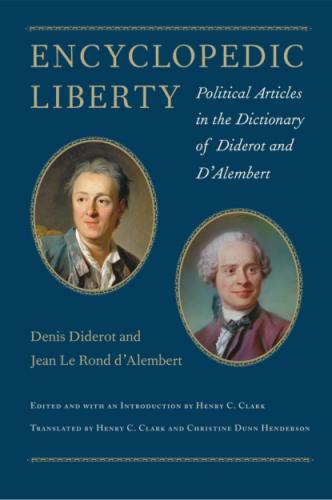

JEAN LE ROND D’ALEMBERT, 1717–83 (1,309 articles). Born illegitimately to the salon hostess Madame de Tencin and the military officer Chevalier Destouches, d’Alembert had a brilliant mathematical mind and became a member of the Royal Academy of Sciences in 1742 at the age of twenty-four. While Diderot sought out the convivial atmosphere of the cafés, d’Alembert, with his high voice and attention to fashion detail, preferred the quieter and more controlled ambience of the salons. He collaborated with Diderot on the early volumes of the Encyclopédie, and his major contribution was the Preliminary Discourse, a lengthy treatise (forty-eight thousand words) that has sometimes been seen as the single most lucid and competent summary of European Enlightenment thought in the entire eighteenth century. The controversy with Rousseau and the authorities over the article GENEVA (1758–59) took its toll on him, however, and he disengaged from the project shortly thereafter. In this volume, d’Alembert’s contribution, in addition to GENEVA itself, is the eulogy for the recently deceased Montesquieu, which reveals his skill at editorial selection and concise summation and which provides one picture of how Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws tended to be viewed in the years after its appearance.

ANTOINE GASPARD BOUCHER D’ARGIS, 1708–91 (4,268 articles). Born in Paris, where his father was a lawyer, Boucher d’Argis was admitted to practice

[print edition page xxvi]

in 1727. He wrote several works on rural and property law from 1738 to 1749 and in 1753 received the post of councillor in the sovereign court of Dombes, which conferred hereditary nobility. That same year he became the legal expert on the Encyclopédie, subsequently becoming one of its most prolific contributors. Though not known for particularly reformist proclivities, he continued to write for Diderot’s work even after it was officially banned in 1758, and he participated in the case of the widow Calas after the execution of her husband in the 1760s. In 1767 he became an alderman of Paris, but afterwards, little is known about his activities, including during the early part of the French Revolution. His son was an active royalist in the Revolution and was executed in 1794.

NICOLAS ANTOINE BOULANGER, 1722–59 (5 articles). Born in Paris into a mercantile family, he was sent to the Jansenist collège (secondary school) of Beauvais for his studies, where he was more interested in mathematics and architecture than in Latin. He worked in the army as a private engineer during the War of the Austrian Succession (1743–44) and entered the ponts et chaussées (roads and bridges) corps in 1745. He began to correspond with naturalists such as Buffon and to develop non-Biblical theories of early history. Named subengineer in 1749, he was assigned to the Paris district in 1751. He stopped working due to illness in 1758, when he moved in with his friend Helvétius, whose recently published De l’Esprit had triggered controversy. The few published writings in his lifetime included much of the long Encyclopédie article DÉLUGE (Flood) as well as the article CORVÉE (Forced labor), which called for reform rather than abolition of the practice, but which still displeased his superiors.

His ambitious unfinished manuscript on the early universal flood and how it shaped human religions and political