None of the other guests lounging in deep armchairs and sofas scattered around near the carved stone fireplace could have guessed from Bronwen’s demeanour that Cliveden had once been her home. Yet for all her self-effacement in the simple navy blue trouser suit she is wearing, there is an undeniable something about Bronwen Astor. Even in her late sixties, she still turns heads just as surely as she did when, in the 1950s, after a spell as a BB C television presenter, she became the public face of one of the most distinguished Parisian fashion houses.

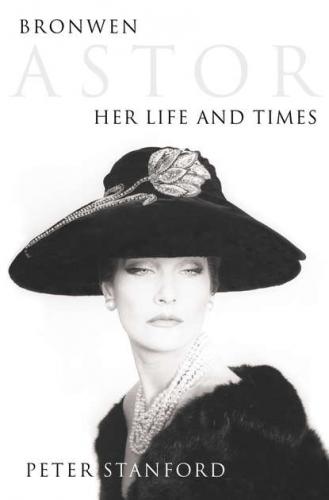

Bronwen Pugh – her maiden name – was the forerunner of today’s supermodels and in her time was just as much a headline-maker and a household name as Kate Moss, Elle MacPherson and Claudia Schiffer are now. She was muse to Pierre Balmain at the height of his fame. He couldn’t pronounce Bronwen so he called her Bella and told the world that she was one of the most beautiful women he had ever met.

Some faces only last a season. Time and fame take their toll. But Bronwen Astor still has it. ‘It’ is something to do with the combination of her height (just under six foot), her bearing (purposeful, haughty, distant) and a certain freedom from conventional restraints. There is, Balmain believed, a Garboesque quality about her. And then there are her eyes – greeny blue, piercing, wild and Celtic, set in a long, elegant, bony face, framed now by strong, wavy grey hair.

Our preconceptions of models today are of visually stunning but empty-headed women. The gloss was taken off Naomi Campbell’s attempt to write a novel when it was revealed that the text had been put together by a ghost-writer. In that sense, a vast gulf separates contemporary fashion superstars from Bronwen Pugh – or ‘our Bronwen’, as the press dubbed her, turning her into a mascot as potent as the Union Jack or the national football team. ‘Our Bronwen leaves them gasping’, the Daily Herald reported proudly from the Paris fashion shows in 1957.

Being a ‘model girl’, a phrase she prefers to the word model, which in her time carried a tawdry undertone, was never more than a distraction – ‘tremendous fun’, as she invariably puts it. By day she worked with Balmain – or a distinguished procession of designers from Charles Creed to Mary Quant who chart the transition from one fashion epoch to another. But in her spare time she was devouring spiritual and psychological writings like the Russian P. D. Ouspensky’s The Fourth Way (published in 1947), which explored new ways of thinking about consciousness, or the books of the French Jesuit and palaeontologist Teilhard de Chardin, who brought Christianity and science closer together than perhaps any other authority this century.

The contrast between Bronwen’s two worlds could not have been greater – one to do with a skin-deep worship of the body and the creations that cover it, the other probing deep and complex matters concerning the mind and the soul. It made for a curious and ultimately untenable double life. A career in the most material of worlds thrived while her mind was fixed on spiritual concerns. Perhaps that accounted for the distant look that Balmain recognised.

The inter-relation – indeed often competition – between these two elements dominates her life story. She loved her husband in a conventional way but also felt guided towards him by God. At Cliveden she was pulled in opposite directions, acting the chatelaine of a great house but unable for the most part to talk of her inner life even to her husband. Occasionally someone would reveal him- or herself to be on a similar wavelength. Alec Douglas-Home is one name she recalls, but usually she preferred to keep quiet. Only in more recent times has she found fulfilment as a practising psychotherapist and a devout, sacramental, if otherwise unconventional Catholic.

It is not until she settles down next to me on the sofa that Bronwen allows herself a proper look around the Cliveden hall. ‘The tapestries are still the same,’ she says, gesturing with those eyes at three great wall-hangings that face the main entrance. ‘But everything else is different. New.’ She strokes the sofa arm. Her tone is almost casual. Almost. ‘It was all sold, you see. Each of Bill’s brothers got to choose a picture and I took some things for my new home, but everything else was sold.’ Her life with Bill went under the hammer – 2,000 lots snapped up by eager collectors.

On Bill’s premature death in 1966 – from heart failure brought on by the strain of his public disgrace as, allegedly, a player in that landmark of the sixties, the Profumo scandal – the Astor trustees, acting on behalf of Bronwen’s stepson and Bill’s heir, then a minor, decided to relinquish the lease on Cliveden. They handed it back to the National Trust, to which Bill’s father had bequeathed it in 1942. In August 1966 Bronwen Astor and her two daughters, aged four and two, left Cliveden with unseemly haste. In the thirty-three years since, she has only been back inside twice.

When I was a small child I used to have a recurrent nightmare. My parents would move out of our family home and other children would take over the nooks and crannies, hiding holes and secret places in the garden that were properly mine. I would be hiding behind the hawthorn hedge watching them play on my lawn, put their toys in my cupboards, climb the narrow stairs to my playroom, take my cup and saucer out of my special cupboard in the kitchen. They would spot me and ask me to join them. I didn’t know how to respond. I always woke up at that stage.

The dream was never realised, but it took me years to recognise that memories are more than bricks and mortar. For Bronwen Astor, the scale is increased tenfold – she was an adult; this was her marital home where she spent five and a half years with the man who was the love of her life; and Cliveden is considerably grander than my suburban house.

After Bill’s death she had hoped to stay on for at least part of the year, so that her children and her stepson, who had lived with them at Cliveden, could remain together as a family; but she was informed by the trustees that she had to leave. It was a traumatic time. ‘For many years,’ she says, ‘I couldn’t bear to come here, but now it is like looking in on another person’s life.’

Again there is that ability to withdraw to another level of consciousness. I sense she is watching herself disinterestedly as she did on the catwalk as she wanders around the grand entertaining rooms that lead off the hall – rooms where once she played hostess to Bill’s friends from the worlds of politics, international charity work, racing and society. ‘I trod a tightrope,’ she recalls. ‘I tried to live a life among people who came from a different class to me but also to remain who I was. The class system was much stronger then. There was a distaste – always in the background. I was not upper class. My husband’ – and her laugh banishes a darker memory – ‘didn’t like the way I said “round”. He used to try to teach me to say “rauwnd”.’

Her diction, though, is perfect. As a young woman she trained at the Central School of Speech and Drama as a teacher. However much she makes herself sound like Eliza Doolittle, her upbringing was solidly middle class, the privately educated daughter of a Welsh county court judge. Indeed, Lord Longford, an old friend of both Bill and Bronwen Astor, is fond of remarking that, such was her poise when greeting him at Cliveden, his practised eye always took her for the daughter of a duke.

The wool-panelling of the library has been treated, she notices, to make it lighter. She stands close and sniffs it. Amid the formality of a smart hotel it is a curiously relaxed gesture, as if this is still home. Yet one of the smells that she associates with Cliveden has gone.

Outside the window of what was once her drawing room – now the hotel’s dining room – she points out the metal cups set in the balustrade around the terrace that looks out, in Cliveden’s most celebrated view, onto the Thames as it meanders down to London. ‘We used to put an awning up there and eat out in the summer.’

It must, I suggest, have been like living in a huge museum cum art gallery. Even the balustrade had been brought by Bill’s grandfather from the Villa Borghese in Rome. ‘My first impression, I think, was that it was all very cosy. It sounds strange now, but all the rooms lead off the hall and off each other and Bill had a flair for