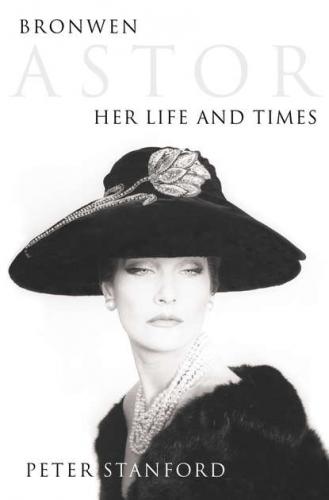

Bronwen Astor

HER LIFE AND TIMES

Peter Stanford

To Mary Catherine Stanford

1921–1998

whose love and nurturing is behind

everything in my life and whose loss

will always be unbearable

Contents

Prelude: Cliveden, Berkshire, 1999

Postscript: Tuesley Manor, Surrey, 1999

‘Lady Astor’s back.’ In the silence of the main hall at Cliveden, now a hotel, this snippet of understairs gossip hangs for just a second in the air, then disappears before I can catch the intonation. Excited? Nervous? Indifferent? Puzzled? Simply reading the guest list for lunch? Does the cleaner, waitress or under-manager responsible for this sotto-voce broadcast even know which Lady Astor she is talking about?

Cliveden, this most famous – and twice this century notorious – of English stately homes, is today a shrine to its most celebrated inhabitant, Nancy, Lady Astor, the first woman to take her seat in the British Parliament. That was back in 1919, but in the timeless opulence of the wood-panelled hall decades and even centuries merge. In such a self-consciously impressive place, it is hardly a challenge to imagine the redoubtable Nancy sweeping in, all long skirts, fur collars and button boots, barking at her servants in the Virginian drawl that she never lost after almost a lifetime on the British side of the Atlantic, and greeting the houseguests assembled for one of the gatherings of what was mistakenly labelled the ‘Cliveden set’ of Nazi appeasers in the late 1930s.

Yet the Cliveden visitors’ book was far more eclectic than that. In the 1910s, 1920s and 1930s kings, prime ministers, world leaders and Hollywood stars came for the weekend to Cliveden to be entertained by this witty, sharp and unfailingly direct woman. Edward VII, Franklin Roosevelt, George Bernard Shaw, Mahatma Gandhi and Charlie Chaplin all fielded Nancy Astor’s barbs and bouquets over feasts in the ornate French dining room which once graced Madame de Pompadour’s chateau near Paris. Joseph Kennedy, American ambassador to London in the 1930s, brought his brood to stay at Cliveden, linking across decades and thousands of miles one Camelot with another.

As if on cue, Lady Astor arrives. Not Nancy but Bronwen, her successor as mistress of this Palladian mansion which peers down imperiously from its hilltop over the Thames. As she comes through the main doors, she hesitates for a beat before she meets my eyes and walks over to the plush but anonymous hotel settee near the open fire. Later, when more relaxed, she admits that she had stopped in a lay-by near the main entrance to collect her thoughts and pray so that she could walk calmly into her old home. ‘I always used to do it before I lived here and was visiting – as a preparation to face my future mother-in-law.’

Nancy and Bronwen, both Lady Astors, overlapped for less than four years. Bronwen arrived in October 1960 as the third wife of Nancy’s son and heir, Bill. Nancy died in May 1964. Theirs was neither a long-lived nor a close friendship. They could hardly even be described as friends. Bronwen sought to placate her mother-in-law, who was unfailingly critical of everything she did. In her declining years Nancy was not the force she had once been, her wit extinguished and replaced by a certain brutality. Living mainly in London in exile from Cliveden, which she only visited by invitation, she grew bitter and resentful.

Bronwen’s treatment was not