A week later I was packing. As it turned out, I needed just a single suitcase.

I almost wept with self-pity. After all, I was thirty-six years old. Had worked eighteen of them. I earned money, bought things with it. I owned a certain amount, it seemed to me. And still I only needed one suitcase – and of rather modest dimensions at that. Was I poor, then? How had that happened?

Books? Well, basically, I had banned books, which were not allowed through customs anyway. I had to give them out to my friends, along with my so-called archives.

Manuscripts? I had clandestinely sent them to the West a long time before.

Furniture? I had taken my desk to the secondhand store. The chairs were taken by the artist Chegin, who had been making do with[4] crates. The rest I threw out.

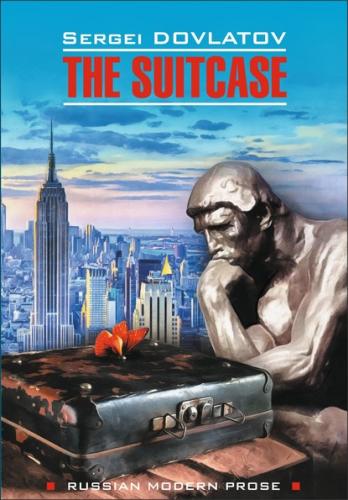

And so I left the Soviet Union with one suitcase. It was plywood, covered with fabric and, had chrome reinforcements at the corners. The lock didn’t work; I had to wind clothes line[5] around it.

Once I had taken it to Pioneer camp. It said in ink on the lid: “Junior group. Seryozha Dovlatov.” Next to it someone had amiably scratched: “Shithead”. The fabric was torn in several places. Inside, the lid was plastered with photographs: Rocky Marciano, Louis Armstrong, Joseph Brodsky, Gina Lollobrigida[6] in a transparent outfit. The customs agent tried to tear Lollobrigida off with his nails. He succeeded only in scratching her. But he didn’t touch Brodsky. He merely asked, “Who’s that?” I said he was a distant relative…

On May 16 I found myself in Italy. I stayed in the Hotel Dina in Rome. I shoved the suitcase under the bed.

I soon received fees from Russian journals. I bought blue sandals, flannel slacks and four linen shirts. I never opened the suitcase.

Three months later I moved to the United States, to New York. First I lived in the Hotel Rio. Then we stayed with friends in Flushing. Finally, I rented an apartment in a decent neighbourhood. I put the suitcase in the back of the closet. I never undid the clothes line.

Four years passed. Our family was reunited. Our daughter turned into a young American. Our son was born. He grew up and started misbehaving. One day my wife, exasperated, shouted, “Into the closet, right now!”

He spent about three minutes in there. I let him out and asked, “Were you scared? Did you cry?”

He said, “No. I sat on the suitcase.”

Then I took out the suitcase. And opened it.

On top was a decent double-breasted suit, intended for interviews, symposiums, lectures and fancy receptions. I figured it would do for Nobel ceremonies, too. Then a poplin[7] shirt and shoes wrapped in paper. Beneath them, a corduroy jacket lined with fake fur. To the left, a winter hat of fake sealskin. Three pairs of Finnish nylon crêpe[8] socks. Driving gloves. And last but not least, an officer’s leather belt.

On the bottom of the suitcase lay a page of Pravda from May 1980. A large headline proclaimed: “LONG LIVE THE GREAT TEACHING!” From the middle of the page stared a portrait of Karl Marx[9].

As a schoolboy I liked to draw the leaders of the world proletariat – especially Marx. Just start smearing an ordinary splotch of ink around and you’ve already got a resemblance…

I looked at the empty suitcase. On the bottom was Karl Marx. On the lid was Brodsky. And between them, my lost, precious, only life.

I shut the suitcase. Mothballs rattled around inside. The clothes were piled up in a motley mound on the kitchen table. That was all I had acquired in thirty-six years. In my entire life in my homeland. I thought, “Could this be it?” And I replied, “Yes, this is it.”

At that point, memories engulfed me. They must have been hidden in the folds of those pathetic rags, and now they had escaped. Memories that should be called From Marx to Brodsky. Or perhaps, What I Acquired. Or simply, The Suitcase.

But, as usual, this foreword is beginning to drag.

The Finnish Crêpe Socks

This happened eighteen years ago, when I was a student at Leningrad University.

The university campus was in the old part of town. The combination of water and stone creates a special, majestic atmosphere there. It’s hard to be a slacker under those circumstances, but I managed.

Since there is such a thing as the exact sciences, there must also be the inexact sciences. It seems to me that first among the inexact sciences is philology. And so I became a student in the philology department.

A week later a slender girl in imported shoes fell in love with me. Her name was Asya. Asya introduced me to her friends. They were all older than us – engineers, journalists, cameramen. One was even a store manager. These people dressed well. They liked going to restaurants and travelling. Some had their own cars.

Back then they seemed mysterious, powerful and attractive. I wanted to belong to their crowd. Later many of them emigrated. Now they’re just regular elderly Jews.

The life we led demanded significant expenditures. Most often they fell on the shoulders of Asya’s friends. This embarrassed me considerably. I still remember how Dr Logovinsky slipped me four roubles while Asya was hailing a cab[10] …

You can divide the world into two kinds of people: those who ask, and those who answer. Those who pose questions, and those who frown in irritation in response.

Asya’s friends did not ask her questions. And all I ever did was ask, “Where were you? Who did you meet in the subway? Where did you get that French perfume?”

Most people consider problems whose solutions don’t suit them to be insoluble. And they constantly ask questions to which they don’t need truthful answers.

To cut a long story short, I was meddlesome and stupid.

I acquired debts. They grew in geometric progression. By November they had reached eighteen roubles – a monstrous sum in those days. I learnt about pawnshops with their stubs and receipts, their atmosphere of dejection and poverty.

When Asya was near I couldn’t think about it. But as soon as we said goodbye, the thought of my debts floated in like a black cloud. I awoke with a sense of impending disaster. It took me hours just to convince myself to get dressed. I seriously planned holding up a jewellery store. I was convinced that all the thoughts of a pauper in love were criminal.

By then my academic success had diminished noticeably. Asya hadn’t been an outstanding student to begin with. The deans began talking about our moral image. I noticed that when a man is in love and he has debts, his moral image becomes a topic of conversation.

In short, everything was horrible.

Once I was wandering around town looking for six roubles. I had to get my winter coat out of hock. And I ran into[11] Fred Kolesnikov.

Fred was smoking, leaning against the brass rail of the Eliseyev Store. I knew he was a black marketeer[12]. Asya had introduced us once. He was a tall young man, about twenty-three years old, with an unhealthy complexion. As he spoke, he smoothed his hair nervously.

Without a second thought, I went over to him. “Could you lend me six roubles until tomorrow?” I tried to act pushy when I borrowed money, so that people could turn me down easily.

“Without a doubt,” said Fred, taking out a small, square wallet.

I regretted not asking for more.

“Take more,” said Fred.

Like a fool, I protested.

Fred looked at me curiously.

“Let’s have lunch,”