“Indeed, sir?”

“They must be over here.”

“It would seem so, sir.”

“Awkward, eh?”

“I can conceive that after what occurred in New York it might be distressing for you to encounter Miss Stoker, sir.”

“Jeeves, do you mean that I ought to keep out of her way?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Avoid her?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Moreover, they were accompanied by Sir Roderick Glossop[4].”

“Indeed, sir?”

“Yes. It was at the Savoy Grill[5]. And the fourth member of the party was Lord Chuffnell’s aunt, Myrtle[6]. What was she doing in that gang?”

“Possibly her ladyship is an acquaintance either of Mr Stoker, Miss Stoker, or Sir Roderick, sir.”

“Yes, that may be so. But it surprised me.”

“Did you enter into conversation with them, sir?”

“Who, me? No, Jeeves. I ran out of the room. If there is one man in the world I hope never to exchange speech with again, it is that Glossop.”

“I forgot to mention, sir, that Sir Roderick called to see you this morning[7].”

“What!”

“Yes, sir.”

“He called to see me?”

“Yes, sir.”

“After what has passed between us?”

“Yes, sir. I informed him that you had not yet risen, and he said that he would return later.”

“He did, did he?” I laughed. “Well, when he does, set the dog on him[8].”

“We have no dog, sir.”

“Then step down to the flat below and borrow Mrs Tinkler-Moulke’s Pomeranian[9]. I never heard of such a thing. Good Lord! Good heavens!”

And when I give you the whole story, I think you will agree with me that my heat was justified.

About three months before, noting a certain liveliness in my Aunt Agatha, I had decided to go to New York to give her time to blow over[10]. And in a week, at the Sherry-Netherland[11], I made the acquaintance of Pauline Stoker. Her beauty maddened me like wine.

In New York, I have always found, everything is very fast. This, I believe, is due to something in the air. Two weeks later I proposed to Pauline. She accepted me. But something went wrong.

Sir Roderick Glossop, a nerve specialist, nothing more nor less than a high-priced doctor, he has been standing on my way for years. And it so happened that he was in New York when the announcement of my engagement appeared in the papers.

What brought him there? He was visiting J. Washburn Stoker’s second cousin[12], George. This George had been a patient of Sir Roderick’s for some years, and it was George’s practice to come to New York every to take a look at him. He arrived on the present occasion just in time to read over the morning coffee and egg the news that Bertram Wooster[13] and Pauline Stoker were planning to marry. And, I think, he began to ring up the father of the bride-to-be.

Well, what he told J. Washburn about me I cannot, of course, say: but, I imagine, he informed him that I had once been engaged to his daughter, Honoria[14], and that he had broken off the match because he had decided that I was an idiot. He would have told, no doubt, about the incident of the cats and the fish in my bedroom: possibly, also, on the episode of the stolen hat with a description of the unfortunate affair of the punctured hot-water bottle at Lady Wickham’s[15].

A close friend of J. Washburn’s and a man on whose judgment J. W. relied, I am sure that he had little difficulty in persuading the latter that I was not the ideal son-in-law[16]. At any rate[17], as I say, within a mere forty-eight hours of the holy moment I was notified that it would be unnecessary for me to order the new trousers and flowers, because my nomination had been cancelled.

And it was this man who dared to come at the Wooster home! I thought that he was going to say that he was sorry for his doing wrong.

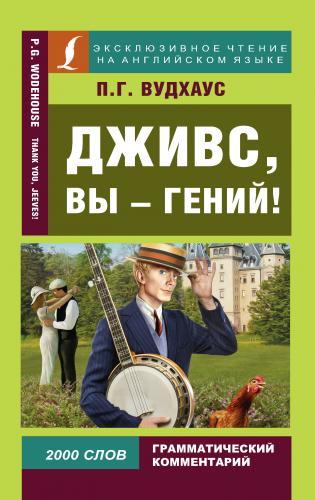

I was still playing the banjolele when he arrived.

“Ah, Sir Roderick,” I said. “Good morning.”

His only reply was a grunt, and an indubitably unpleasant grunt. I felt that my diagnosis of the situation had been wrong. He was glaring at me with obvious distaste as if I had been the germ of dementia praecox[18].

My geniality waned. I was just about to say the old to-what-am-I-indebted-for-this-visit, when he began:

“You ought to be certified!”

“I beg your pardon?”

“You’re a public menace[19]. For weeks, it appears, you have been making life a hell for all your neighbours with some hideous musical instrument. I see you have it with you now. How dare you play that thing in a respectable block of flats? Infernal din!”

I remained cool and dignified.

“Did you say ‘infernal din’?”

“I did.”

“Oh? Well, let me tell you that the man that hath no music in himself…” I stepped to the door. “Jeeves,” I called down the passage, “what was it Shakespeare said the man who hadn’t music in himself was fit for?”

“Treasons, stratagems, and spoils, sir.”

“Thank you, Jeeves. Is fit for treasons, stratagems, and spoils,” I said, returning.

He danced a step or two.

“Are you aware that the occupant of the flat below, Mrs Tinkler-Moulke, is one of my patients, a woman in a highly nervous condition. I have had to give her a sedative.”

I raised a hand.

“Don’t tell me the gossip from the loony-bin[20],” I said distantly. “Might I inquire, on my side, if you are aware that Mrs Tinkler-Moulke owns a Pomeranian?”

“Don’t drivel.”

“I am not drivelling. This animal yaps all day and night. So Mrs Tinkler-Moulke has had the nerve to complain of my banjolele, has she? Ha! Let her first throw away her dog.”

“I am not here to talk about dogs. Stop annoying this unfortunate woman.”

I shook the head.

“I am sorry she is a cold audience, but my art must come first.”

“That is your final word, is it?”

“It is.”

“Very good. You will hear more of this.”

“And Mrs Tinkler-Moulke will hear more of this,” I replied, taking the banjolele.

I