In my mother’s memory, it’s been a wonderfully exhausting day at the carnival; she feels a quiet sense of peace, nestled in the warmth of woolen blankets and the slight glow of the streetlamp outside her grandpa’s living room. It is well past midnight, beyond the cliffhangers of the weekend radio serials, Dragnet and Mr. District Attorney, when her eyelids began to flutter at last, drooping heavily. The ominous music for the next episode of The Shadow swells from the cloth-covered speakers, a slight crackle in the background of the chilling narration, and she drifts off to sleep knowing that for this moment, all in her little world is perfect.

CHAPTER 7

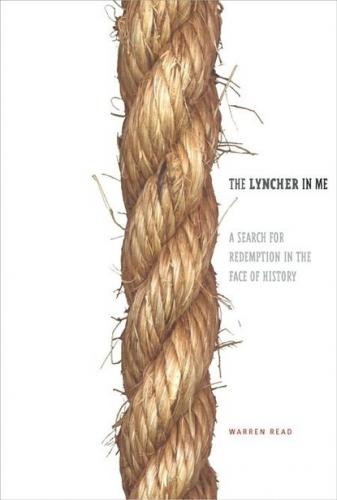

Family trees, census data, anecdotal tales, and even photographs can give a person a rudimentary, one-sided view of his or her family. Dates, names, and trivia begin to fill in the puzzle. A picture posed and taken under the best of light with the subject carefully still will capture a moment in time, often when things are at their best and most presentable. Like a thousand-piece jigsaw puzzle, the completed image can be detailed and colorful, but sadly lacking any real depth.

When I discovered the Ripsaw News article I began to collect the complex pieces of history that would help me form the outline of my own complicated puzzle. With those bits of data would come a flood of questions about my great-grandfather, the young Louis Dondino. What kind of life had he made for his son? What about the community he lived in? What was Duluth like in the early twentieth century? How did African Americans fare in this northern city nearly fifty years after emancipation?

Context can explain an action, but seldom does it excuse. I’ve always maintained this—with myself, my children, my students. Still, I knew I would have to seek my explanations with the hope that they would help provide an understanding I so desperately needed. Only when one truly understands the whole picture of an action, I feel, can one begin to take responsibility for it. To understand the context of that night in June of 1920 I would need to reconstruct the life of my great-grandfather, and my grandfather, as vividly as possible. As in my garden, before I could even consider tilling the soil to reform the landscape, I would need to educate myself and truly understand what had come before me in order to create the pathways that would be there after.

Before I discovered the Ripsaw News article I’d known a few basic facts about my great-grandfather’s younger days. His wife had died when his son, my grandfather Ray, was a young boy and Louis had raised him with occasional help from his own parents. His parents lived on a farm. Louis worked as a logger; oftentimes his son, Ray, was forced to live in a Catholic orphanage. There was intense anger and bitterness between the two men that lasted until both of their deaths. That was about all I knew: a few clues and a lot of empty space. I did the math in order to create a readable timeline, studied the geography to gain a sense of place, and painstakingly scoured the history. Over time, I was able to pull together a reasonable life’s portrait of the man who would come to be a beloved patriarch to one family, a vilified mob leader to countless others. And with this portrait, the emptiness shrank and the understanding grew.

* * *

By 1920, my great-grandfather Louis had lived in the Great Lakes area nearly all of his thirty-eight years. Born in Meade, Michigan (a town I’ve not been able to find any mention of today), in 1882, he was the second of six children, his only sister being the eldest. His father and mother, William and Sarah, emigrated from Ontario to Michigan in 1860 when they were both sixteen, settling the area to farm.

It’s a common assumption that the Dondino lineage was Italian, given the spelling of the name. However, Louis’s parents did not speak or write English, and the story goes that when they told an immigration official their last name was Dondineau, the impatient and ill-informed clerk wrote it as Dondino. To this day, there are Dondinos and Dondineaus throughout the Great Lakes region whose ancestry is very likely linked somehow. To further confuse the matter, records of enlisted men in William’s Civil War division show his name as Dandenon, Dondeno, and, as it is on his headstone, Dandenow. As in a lot of genealogy research, the variations in spelling are frustratingly difficult to differentiate.

William and Sarah moved with their infant son, Louis, and his older sister from Meade to Duluth, Minnesota, in 1882. The 1880s had been a booming time for the port city, especially in the production of lumber and lumber products. Thanks to the railroads and shipping routes through Lake Superior connecting Duluth commercially to the markets of Chicago, Cleveland, and the great Atlantic coast cities, by 1884, Duluth mills would operate at a capacity of thirty million board feet of lumber annually. Elevators, lumber warehouses, and expansive docks had been built to accommodate the growing industry, and the population of Duluth had grown right along with it. From 1880 to 1890, Duluth’s population would rise from about seven thousand to nearly forty thousand. The Dondinos’s arrival in Duluth in 1882 coincided with a severe typhoid epidemic that was ravaging the city. St. Luke’s Hospital, the first in Duluth, had just opened its doors above a blacksmith’s shop for the sole purpose of tackling the outbreak. For my ancestors and countless others, the future was both a promise and a terrifying prospect. Fortune could be had just as easily as death.

* * *

It hadn’t been the discovery of the lynching that had surprised me. The concept was certainly not foreign to me. My grandmother Margaret had been born and raised in Mississippi; growing up, I’d been all too aware of the realities of violent racism that had been part of the culture of her own young life. Westerns on Saturday-afternoon television often showed a lynching or two, a portrayal of earned justice for horse thieving or stagecoach robbing. But the idea that a mob lynching could have happened in the north, far from the KKK rallies and cross-burnings of the Deep South, still seemed like an anomaly. It wasn’t, though, as I would discover over and over again. In early American culture, lynchings had been a form of vigilantism practiced throughout the land, regardless of the condemned man’s (or woman’s) race.

In late April of 1882, the same year that my great-grandfather settled in Duluth with his parents, a twenty-five-year-old Irish metalworker was arrested in Minneapolis, just a day’s trip by rail from the Dondinos’s new home. Frank McManus had moved to the City of Lakes five years previously, having spent much of his adult life working in the iron mills of Boston. Upon his arrest, McManus was taken to the Minneapolis city jail and hidden away securely—for good reason. Police speculated that when word got out that this man had brutally raped the four-year-old daughter of J. P. Spear, a local tin-manufacturing worker, there was likely to be trouble. And sure enough, by two the next morning, it showed up at the jail—sixty men strong.

The mob forced their way in, using a large timber as a battering ram, and demanded the sheriff lead them to the prisoner. The sheriff refused, but a frightened night watchman directed them to cell number three, on the upper tier of the jailhouse. McManus was quickly found; the mob swarmed over him, cuffed his wrists, and took him to the Spear home for positive identification. While her daughter lay dying in the next room, Mrs. Spear shook, glaring at the shackled McManus. “It is the man,” she cried. “Take him away.”

The men led McManus from the Spear home to a bare oak tree, carefully arranged the noose around his neck, and asked him if he had anything to say. McManus continued to proclaim his innocence, identifying himself as one Tim Crowley, son of Nancy Ann Crowley of South Boston. He whispered a message to one of the vigilantes that was to be delivered to his mother before finally confessing to the rape, with the rationale that he had been drunk when he’d assaulted the little girl. With nothing left to be said, the men tied McManus’s hands behind his back and he was “swung off.”

A photograph of the lynching was taken and issued as a postcard (not unusual at the time), perhaps as a warning to other men who might contemplate such an act. In the photo, the mob of hundreds, wearing hats and dressed in suits and ties, dominate the black-and-white image. If not for the solitary figure dangling from a branch (he almost looks as though he’s standing on the shoulders of the crowd) it could be a group of revelers posing at a parade or a sporting event. Hands folded or planted firmly on hips; broad, satisfied grins; all before