* * *

I stood in the open space of my newly turned garden, my boots sinking in the soft black soil, my gloves gripping the rake as I pulled it through the till. I paused every few yards to turn the rake head upward and pick out the snags of roots and weeds that had found their way into the teeth. Dandelion taproots and starts of unwanted brush went into the wheelbarrow, and the gentle singsong of my youngest son Dmitry’s voice drifted from the sand pile, in cadence with the scratching of his tiny shovel and my ancient rake. It was a nursery rhyme, I’m sure, though I can’t recall exactly which one. There were a half-dozen or so in his repertoire. I’d picked up the verse with him, like I usually did, and he’d turned to look at me, smiling as the two of us finished with dramatic flair.

And the irony of it all washed over me with the sound of the nursery rhyme, just as clear, just as simple as the melody of that silly song. I was a father to a son of my own, like Mr. Brady and Mr. Eddie’s Father, and my responsibility to him was something I could not wander through blindly, like I had my garden, figuring it out along the way and hoping that I would discover the right path. I was at a place of opportunity. My son didn’t fear me, didn’t take pains to avoid me. The patterns we were beginning to create were good; small rituals that made us laugh and look forward to doing it all again.

Our children are born as clean slates, it is said, but that’s not true at all. Genetics mark us with a map already in place. A packet of seeds I put into the dirt is pretty predictable, as long as I do what’s required to raise the plant to adulthood. But climate, nutrients, pests—all can affect the plant’s life. Our family, the crucial people in our lives, are like gardeners, nurturing us through the seasons, influencing us with their actions, their habits, their words. Our son came to us when he was nearly eighteen months old; his life had already begun in earnest, so it was our task as his new parents to shepherd him the rest of the way. His genetic slate may have been already in place, but his journey was and is far from complete. For that matter, so is mine.

I realized then that if I wanted to ensure an optimal environment for my child, to completely move outside the patterns of dysfunction that continued to creep up in my life, I would need to get to a place where I understood—truly understood—the unhealthy foliage that filled my own family tree. And to do this, to grasp the origins of my flashes of anger, the discomfort of seeing and hearing my last name used in conjunction with my first, the minor recoil I did when black-and-white family photos showed resemblances to my father that were undeniable, I would need to begin clearing the soil from the roots of my family tree, scraping away at the dirt and detritus to see what was really there. Looking at the branches would give me some names and a few facts; this I knew. To get at the heart of my family—the essential elements of me—I would have to dig as well, to uncover the roots hidden deep beneath the surface.

The more we dig, of course, the more we uncover. I can still see an image of my seven-year-old self with a neighbor pal; we are using my mother’s tarnished serving spoon to excavate the remains of an old home site in the woods behind our house. The promise of buried treasure is exhilarating and even the end result, an old pint whiskey bottle, can’t quench our rabid curiosity. I found myself pulled to the treasure hunt of genealogy, the search for the ancient footprints of my family, in the same way. The very notion of finding something precious, some amazing fact that might redeem my ominous memories, was a call that grew louder the more I tried to quash it. I really wanted something good, something of which to be proud. But the path that appeared in front of me, sometimes bright, often nearly indiscernible, was one over which I had no control. A turn here, a dead end there, the trail would continue meanderingly until one night a startling, horrific find—one from which there would be no turning back.

CHAPTER 6

A fine stretch of summer days moved into the drizzly early dusk that is the trademark of the Pacific Northwest and I found myself finally able to settle in and devote more time to genealogical research. Night after night I sat at the computer, following one lead into another, collecting intriguing bits of identifying information on my parents’ various ancestors. The fact that there were people out there in the world, individuals whom I would never meet who were connected to me by some distant, far-reaching twig of the family tree was mind-boggling. They’d already laid the groundwork for me, recording names, dates, and birthplaces; I could take what I learned from one source and connect it to another found resource. It was giant jigsaw puzzle, the edges forming a frame and the interior just beginning to come into view. And then suddenly, after weeks of deciphering the great arching familial maps that had been created and posted on Web sites for all to see, I’d stumbled upon the final piece to the puzzle that, up to then, had perplexed me to no end. Old Uncle George had not been kidding.

While the search for my father’s side of the family had been going swimmingly (forefathers in Wales, a surprise Jewish ancestor, an owner of a sugar plantation), my mother’s side had proven to be frustratingly vacant. I found a bit about my mother’s maternal side, a maiden name here and there, and that was all. It baffled me. With a family name like Dondino, how could there not be usable results? There were Dondinos living in Italy, but I knew they were not my Dondinos. After weeks of futile searching, I’d assumed I was finished and that what little I’d found was all there was to be found.

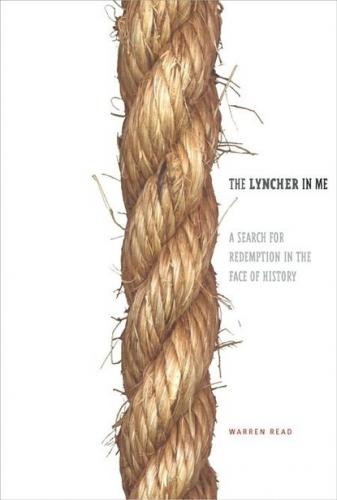

Some weeks later I was browsing at the newsstand, killing time between errands, and I picked up an issue of a computer tech magazine. I’m not a tech-savvy kind of person, but a blurb on the cover about genealogical searches caught my attention. The article inside listed a half-dozen search engines that I hadn’t yet tried. When I got home that night, I decided I would try to find my mother’s family once more, see if in fact these additional tools would work where the other ones hadn’t. I wasn’t optimistic. I sat down at the computer and put the list of search engines in front of me. Fingers on the home row, I entered the first URL and pecked away at the familiar search terms, Dondino and Minnesota. Within seconds, a heading I hadn’t seen before popped up and the subtext was stunning. There was something about a rape, references to a lynching—and it had taken place in Duluth. An ominous feeling crept over me as I clicked on the link and began to read, scanning warily, baffled over where my family’s name would appear.

As I stared at the monitor, horrified, eyes burning and gut slowly knotting, the growing clarity of truth began to sink in. I scrolled down the text haltingly, my hands shaking. The link had led me to the June 7, 2000, issue of the Ripsaw News, a weekly news and entertainment newspaper in Duluth, Minnesota. The article was titled “Duluth’s Lingering Shame” and in it, writer Heidi Bakk-Hansen chronicled the night of June 15, 1920, when six black circus workers had been arrested in connection with the alleged rape of a white teenaged girl, accused by the girl and her boyfriend. Within hours, a mob of somewhere between five and ten thousand townspeople clamored around the Duluth city jail demanding vigilante justice. In the end, three of the six men hung dead from a nearby lamppost and a community struggled to come to grips with the awful truth that, once the facts reached the light of day, no assault had actually happened. The men had been innocent; the girl and her boyfriend had been lying.

As I read through the article, my initial excitement over discovering new information turned to trepidation and then dread as I began to realize that I was about to find something that might very well change everything I thought I knew about my family. About two-thirds of the way through the article, I came across a name that up until then I’d have given anything to find. Now, I was hoping it was somebody else.

Few members of the lynch mob received any punishment. Two who did stand trial, Henry Stephenson and Louis Dondino, served less than half of their five-year sentences for rioting.

My mind was spinning, not just at the news with which I’d suddenly been hit, but with the realization that I would very soon be forced to share this unthinkable story with my mother. That up until that moment I’d subscribed to an idealized view of my great-grandfather. To my mother, her grandfather