Simone Arnold Liebster’s autobiography restores individuality and identity to the otherwise anonymous victims of the Nazis and reveals her strength of will to maintain whatever normality was possible in her fight for physical and psychological survival. Her story is one of hope, strength, and courage. Despite the harsh and tragic Nazi period, Simone Liebster’s narrative reveals her courage in maintaining her social and religious values. It is a story worth reading and enables us to understand the fate of Jehovah’s Witness children during the Holocaust.

— Sybil Milton, former Senior Historian, U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum Spring 2000

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I have told this story as accurately as I can remember it, but I am grateful to many people who helped me put my account in its present form. Among them are Germaine Villard, Francoise Milde, Adolphe Sperry and his granddaughter Virginie, and Esther Martinez, who all did historical research to confirm the events and places I remembered. I also compared notes with Rose Gassmann and Maria Koehl, who have vivid eyewitness recollections of their own. Mrs. Bautenbacher at the Wessenberg’sche Erziehungsanstalt fur Mädels and the staff at the city archives of Constance assisted in obtaining documents relating to my incarceration. Author Andreas Müller, who has written about my husband’s story, also shared interesting background information with me about the activities of the Hitler Youth. Additional documentation and photographic material were supplied by the archives of the Watch Tower Society in Selters, Germany, Thun, Switzerland, and Brooklyn, New York. The Cercle Européen des Témoins de Jéhovah Anciens Déportés et Internés, of which I am a foundation member, also contributed archival material.

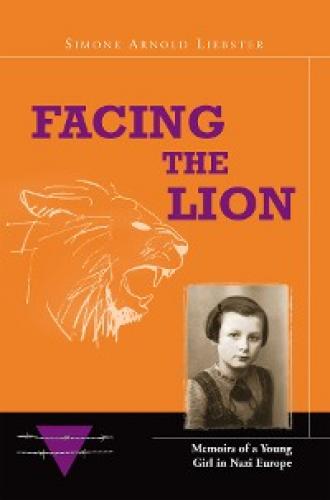

Claudia Walter, Daniel and Nadège Foucher, and Elaine Siegel did the important and tedious work of processing my manuscript. Werner and Michelle Ebstein and Norman Gaydon translated letters and documents for me. Suzanne Glesser applied her considerable creative talent in designing the artwork for the cover. Rick and Carolynn Crandall and their colleagues patiently edited and drew together the various pieces into a coherent work.

Two persons have meant a great deal to me: Fred Siegel, my publisher, whose positive attitude and backing have brought the project to reality, and Eunice Timm, whose meticulous proofreading was indispensable.

The urging of two wonderful friends, the late W. Lloyd Barry and John E. Barr, gave me the needed motivation to write my story.

I must acknowledge a very special debt to Jolene Chu who gave me an enormous amount of help—for illuminating discussions, for her careful review of the manuscript, for her efficient writing skills, and for her cheerfulness, which was a source of encouragement for me. This work has brought us together and has built strong ties between us. I have found in her a daughter who could chronicle my story as if it were her own heritage.

Finally, I owe special thanks to my dear husband Max for his exceptionally patient and loving support.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

All over Europe people were getting ready. The fiftieth anniversary of liberation from Nazi terror was designated as a period of remembrance. The world would once again focus on the period often referred to as “the pit,” “hell,” “the age of terror,” or “the night.” The little group of survivors, eyewitnesses who had borne the purple triangle (the concentration camp uniform symbol for the Jehovah’s Witnesses) also had their own commemorations in Strasbourg and in Paris. They traveled to many French towns with an exhibition and told their story. And then came the flood of questions—questions about facts, but also inquiries about life, our lives—piercing investigations that pried my mental shutters open one by one. I felt like I had returned to my childhood. I became “the little one” again, with all her memories, feelings, joys, and fears. Questions shone the spotlight on my dreams and nightmares and made me relive it all. Everything was so vivid, so precise, that I could recall even the smallest details of when I faced the Nazi “Lion” of oppression.

More friends joined the chorus. “Write it all down, draw a portrait, fix your memories. Capture the events now, while there is still time.” Here is my story.

Part One June 1933 – Summer 1941

Part One

June 1933 – Summer 1941

Life Between City and Mountain Farm

CHAPTER 1

Life Between City and Mountain Farm

U

ntil World War II intervened, I was a happy, outgoing child. Little did I know that my life course would be dramatically altered by the war. The Nazis took over our town, my parents were put in concentration camps, and I was put in a home for delinquent girls because I had defied the “Lion” of the new Nazi order. It was a crushing experience that scarred me for many years. Yet my survival is also a testament to the adaptability of the human spirit. My wish is that my story will help others triumph over whatever “Lions” of the future may threaten the human spirit anywhere.

JUNE 1933

My parents and I had come from a village called Husseren-Wesserling in the Thann Valley in the Vosges Mountains near Grandma and Grandpa’s farm. There we had lived in a wonderful cottage surrounded by rose hedges and meadows. We lived in Alsace Lorraine, a region that lies on the border of Germany and France. Ownership of Alsace Lorraine had been disputed for centuries.

I was almost three years old when we and my little dog Zita moved to the third floor of the apartment building at 46 Rue de la mer rouge in the town of Mulhouse. My world was my family. I could not have anticipated the pain, hardships, and terror that lay ahead.

The name of our street, Rue de la mer rouge—Red Sea Street—could serve as a symbol for the fate of my family. Despair. Partings. Journeys. Hope. I wonder if my parents ever remarked upon the street’s name.

The railroad station at Mulhouse-Dornach marked the beginning of Rue de la mer rouge, a long street that wound its way through gardens and fields, past a neighborhood of family homes and apartment houses. Number 46 was a four-story building with eight apartments. It housed workers from the Schaeffer and Company factory, a world-famous manufacturer of textured fabric. Dad was an art consultant for Schaeffer and Company.

Here in the city, I was not allowed to get close to the windows or go out to the street on my own. How sad for a little country girl...even the flowers on the balcony were prisoners of their pots!

Happily, we often returned to my grandparents’ farm. We’d get off the train at Oderen, where there was a chapel for the Virgin Mary. The footpath scaled the mountain; it passed a cool mountain stream and, climbing sharply, followed a rocky cliff to a plateau of green meadows. The meadows were strewn with many different kinds of fruit trees. This isolated area was called Bergenbach.

In the midst of rocks, ferns, and undergrowth, stood my grandparents’ house. After entering through the tiny door, a person’s eyes would have to adjust to the dim light before it was possible to make out the huge black chimney in the corner. Into this chimney, a big kitchen stove had been set. The odor of smoke mixed with the aroma of hay and cereals was the best of fragrances to me. Outside of the