“Nothing, goddamn it, just leave me alone!” my father roared.

My mother sighed. “What’s wrong with him?” she asked, looking at me.

“He couldn’t get his shoes on,” I said, but that wasn’t what she was really asking.

“All this screaming and banging because you couldn’t get your shoes on? Jesus, Sam.”

Anger began to win over my father again. He was so volatile—explosive one moment, despairing a second later. One more push and he’d blow, and this little family reunion would turn into chaos.

My brother began his way down the steps. His footfalls were much heavier than my mother’s. He rounded the corner, nudging her out of the way with his beer belly. Full of attitude, he now stared at the head of the house, laughing to himself like some movie villain at the failed attempts of those who would overthrow him. “What the fuck’s your problem?” he asked.

I’ll answer that one. My dad fell from the roof of our house while he was laying shingles. He fell headfirst, dropping twenty-odd feet before crashing into the rough ground below. He shattered his nose and blew out disks in his neck and back.

I can remember it all, like a memory recalled at the site of a scar. I was the only one home at the time. I heard my father shout, tumble, and hit. I ran from the house to see what had happened and found my father motionless, a pool of blood forming around his face. I asked him if he was okay, even though I knew he wasn’t, but what else is there for a thirteen-year-old son to ask?

He told me, in gurgles and gasps that he couldn’t feel his body, that he couldn’t move. He told me to walk away, to leave him because he was dying, and he didn’t want me to have to see it. I ran into the house and punched 911.

He wouldn’t walk again for two years. After all the rehab, when he could finally stand on his feet without assistance, he was a different man. A shell of one, not the father we had grown to love.

Outsiders would tell me I should be thankful he could walk, what a blessing it was, and all that jazz. I didn’t feel that way about it. Maybe I should’ve, but it wasn’t like the feel-good stories used to sell bracelets with trendy slogans. My dad could walk, but he did so like Frankenstein. He couldn’t feel his hands or his feet. His bowels didn’t wait for his consent to go. His vision suffered and his flexibility disappeared. He couldn’t tell whether he cut his legs or whether he was bleeding. He slept with constant discomfort and medicated himself heavily. When the pills stopped working on their own, he began mixing them with alcohol. The mighty perfectionist was unequipped to deal with his new imperfections. He was disgusted with everything, including himself.

For a time, things plodded along. It seemed as if, despite all of my father’s issues, the family would survive. Things were hard, but we were getting the hang of it. Then dad lost his job—the salary, the benefits, the sense of purpose were all gone. His hands, cumbersome and mangled, could not work the computer keys like they once did. When the company he worked for restructured itself, my dad was restructured by a fresh college graduate with no experience for half the salary.

The termination snuffed out the last remaining pieces my father had to build with. He could not work and so he felt useless. Having already reconciled the demise of his sports hobbies, no longer a softball or basketball player, he was at least a valued member of his work team. Now he was nothing. Coming from the generation that did not require degrees to get a job, any hope my handicapped, undereducated father had of competing in the present market was gone. He had lost his employer and the rest of his identity.

My mother’s job supported us while my father looked for work. Then she too was fired. Suddenly, we had nothing but a few waning months of unemployment. My dad had to take manual-labor jobs and simply could not keep up with the work pace. He was let go from all of them.

My brother turned to the bottle to help him cope. He fell into alcoholism about as hard as my father fell from the rooftop. He was a mean drunk, violent and irrational. He’d toss my crippled father aside like a rag doll. He’d smack my mother, choke her, and knock her down. He’d flat out beat the shit out of me. He put my head through picture frames, through coffee tables, and into hospital beds. He hated me because I was the family golden boy, sheltered by the success sports had brought me. I was the enemy—a relationship I’d become accustomed to.

My brother spent a lot of his early life getting into trouble. He had a poor self-image. ADD and a cleft pallet can do that to a person. When he grew up, failed relationships and drunk-driving charges galvanized him. He was convinced he was a bad egg because all his endeavors met with disastrous results. He dreamed as big as any kid, yet always found himself in situations where no one understood what he was dealing with. Why isn’t he normal? Why doesn’t he look like the other kids? Why can’t he stay on task? And, maybe worst of all, Why can’t he be more like his brother? He would come to wear judgment around his neck like a scarlet letter. The only time he felt relief was when he was drunk.

And so it went. Some days were worse than others, but so common was the domestic violence that the neighborhood cops knew us on a first-name basis. They’d show up and ask if anyone wanted to press charges, and my parents would both say no. When we got hurt, they’d lie about it. We wanted everyone to think we were normal, to keep up appearances. We had a great athlete in the family from a functional home. Nothing was wrong.

Once, when I was so tired of getting my head busted, I made up my mind I was going to lock up my brother and get it over with. I would put an end to the drama. My mom got on her knees and wept at my feet, soaking my ankles with her tears, begging me not to. I told her I had to. It needed to be done because we couldn’t keep living in fear of him. She told me I was just as bad as my brother and threw me out. I grudgingly dropped the charges, but I refused to live at home again. I packed up my tiny ship of dreams and set sail for the horizon. Instead of a bright future, I ran aground on the other side of the city, minutes away from my high school, employed in a run-down machine shop, living under the roof on my grandma’s asylum.

Today I made a pilgrimage back my parents to talk baseball or rather to talk about quitting baseball. Yet watching them tear each other apart, I didn’t have to ask why I should keep playing. If I did it for no other reason than just to escape my home life, it was reason enough.

I stood up from the chaos and walked through their battlefield, out the door, and into the winter wind. I stood in the drive, listening to the echoing shouts, watching them through the window, wondering how to fix it.

There had to be more than this, more to life than titles and jobs and roles to fail at. My father was a broken heap without a purpose. My brother was a drunk and branded a failure—my mother, a victim. What title would brand me? Was I to be the baseball player who didn’t make it? Would I always wear the jersey of a career minor leaguer? Would I be remembered as a washout, a failure, or a nonprospect?

I wanted to find out what I should do with my life from here on. I wouldn’t find it in the chaos of my family. I wouldn’t find hope there either, just a reason to put my key in the ignition and drive on.

Chapter Four

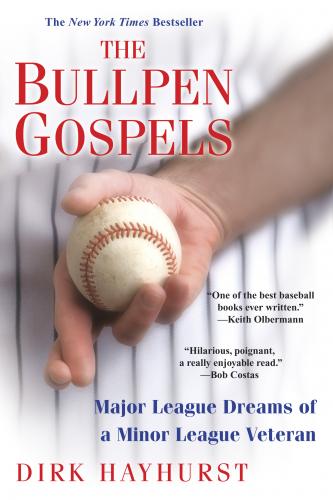

That night, after I met with my family, I lay on my air mattress at Grandma’s, flicking a baseball up into a cloud of swirling thoughts. I sent the ball back spinning in tight, four-seam revolutions, trying to see how close I could make it come to the ceiling without striking it. Next, I tried to make the ball spin like a slider, seams forming a tight, red dot, indicative of a well-spun punch-out pitch. The ball clumsily wobbled up and thunked against the ceiling, then wobbled back down. I caught it on the return; then, irritated, I heaved it into an open suitcase across the room. My bags were packed, though I had no idea why. I couldn’t fix my slider, I couldn’t fix my career, and I couldn’t fix my family. Spring training was around the corner, and the only reasons I had for going was it was better than being at home.

Someone