She shops on my behalf because she says she’s such a great bargain hunter. She nabs great deals, and by “nabs” I mean she takes everything on the shelf in one swoop. She’ll come home with a trunkful: eight chocolate cakes, seventeen loaves of bread, and six gallons of orange juice, all “marked down for a limited time.” You could sit her down and explain it all to her, that we beat the commies and the local supermarket won’t be destroyed by a nuclear attack, but it makes no difference—she won’t stop. When turkeys go on sale, it’ll be Thanksgiving at her house for the next nine days. It’ll be for me anyway, and as long as I keep eating it, she’ll keep buying. I’d gladly invite you over to help me get it all down, but she hates you.

She hates pretty much everyone I know and is never shy about telling why. She hates all the presidents, all her doctors, the family, the guy packing groceries at the Food 4 Less, my girlfriends. None of them can do anything right. She hates the neighbors enough to aim that shotgun I told you about out the window when they set foot on her property. She’s developed colorful nicknames for the folks on the block, like the endearing bunch across the lawn she commonly refers to as “that no-good pack of lying, hillbilly Satanists!”

The Satanic hillbillies, who own three large, friendly dogs, used to mow my grandma’s yard for free until she stepped in dog poop. You should have heard the rant that started. She swore the hillbillies were training the dogs to hold their poop and leave it in great big piles in her yard—mountainous piles, dinosaur turds that suck your foot in like a tractor beam.

She threatened to call the cops on the dogs. Then she threatened to call the cops on the neighbors. Next, she threatened to kill the dogs. Then she threatened to kill the neighbors. It wouldn’t be long until there was freezer-burned dog in the fridge.

She provided a roof over my head, and for that I’m thankful, but my life with her is far from fantasy. She’ll tell you she treats me like a prince. She’ll tell you a lot of things. Like how she saved Einstein from the Nazis or the stretch of Underground Railroad beneath the house. What she won’t tell you is how she keeps me in the sewing room, on an air mattress, with nothing but a card table and a suitcase.

My princely suite is filled with her precious treasures: heirlooms; boxes and boxes of worthless, bought-on-sale heirlooms she plans to pass on to us when she dies. I asked her if I could move a few of her artifacts out of “my” room in the meantime, and she told me no. I said I’d do all the work and she wouldn’t have to lift a finger, but it was still a no. One day I decided to move one single thing: a broken exercise bike about ten years older than me. She called a lawyer when she found it was missing. She was going to sue me for the cost of one dilapidated early 1970s exercise bike. She said she was going to use it, and I had no right to throw away her things. I asked her how much long-distance biking she planned on doing at ninety-one years of age, and she told me to go to hell.

There is a real bed in the house, in one of the other junk-stuffed rooms. It’s wedged in next to an old flannelgraph and books on how Stalin is the Antichrist. The bed is brand new, but I can’t sleep on it. Not that she won’t let me; rather, I can’t because she won’t let me take the plastic off the mattress or the pillows. Ever sleep on Saran wrap? Try it sometime—really opens the pores. I told her princes didn’t sleep on plastic, and she told me to go to hell.

She said taking the plastic off was how things wore out and got dirty. I told her everything eventually wore out and got dirty. She said her things were still around because she took care of them. I told her some things had life expectancies on them, like people, hint, hint.

She told me to go to hell.

“All those things you do for me….” I said, being sure to look her straight in the eyes as I spoke. I learned long ago that you can’t show weakness when you speak to her or she’ll attack. I recounted the list of her services, including, but not limited to, bacon fat, lye soap, the Antichrist, lack of sleep, exercise bikes, and bullet holes. “Chocolate cakes are supposed to make it all better?”

Her face flushed red, and I thought her head would spin around like something from The Exorcist. Anger didn’t help her looks much. Permanently hunched over like some evil scientist’s assistant, if she wore a hood, she could get a job haunting bell towers.

She grabbed my door’s handle and just before slamming it screamed, “If you’ve got it so bad, you can just move out!”

“Good luck with those squirrels.”

“You can go to hell!” came her retort. See, I told you she could hear me through the door.

“Pretty sure I’m already there….” I sighed, and flopped back onto my makeshift bed.

Five minutes later, I reluctantly got up and chased the squirrels out of her feeder in my underwear and pair of snow boots. She asked me what I wanted for breakfast as reward for my good deed. I told her I could really go for some chocolate cake.

We fight about the bedding, the food, the clothes, the neighbors, the squirrels, Harriet Tubman, and whatever else she can think up—every day, one futile battle after the next, always ending the same way. You know, Grandma’s house, Grandma’s law. If I don’t like something she does, she tells me I can just move out, and, of course, she knows I can’t.

This is my life now. I’m a poor twenty-six-year-old professional athlete who lives on the floor at his grandma’s. I don’t make enough money during the minor league season to afford living any other way in the off-season, and as long as I want to keep chasing my dream, I’ll have to sacrifice. She’s about as sweet as the living dead, but she’s my sugar momma, and no matter how bad she treats me, I’ll always keep crawling back to her.

My days start with mornings full of obscenities aimed at woodland creatures banging and screaming. I trudge through the snow and run the squirrels off, but they come back—rinse, lather, repeat. It appears the squirrels and I have a common enemy. I guess maybe we should work together. Someday I could leave the door unlocked and let them in when she’s sedated, watching Judge Judy. They could ambush her. I’d act as if I didn’t know anything. I’d feign devastation to the authorities and make a good sound bite for the local news. As soon as it all passed by, I’d throw the rest of the birdseed out, burn those feeders, and drive off into the night cackling maniacally. But, and this is no joke, she already suspects we’re up to something.

Something about lying in my underwear with snow boots on while my right arm throbbed got me thinking. Suffice to say, this was not how I pictured my life as a professional baseball player. Me shacking up with the withered old puppet of evil I called grandma, hanging on to a crumbling dream while the world passed me by, is not how things were supposed to go.

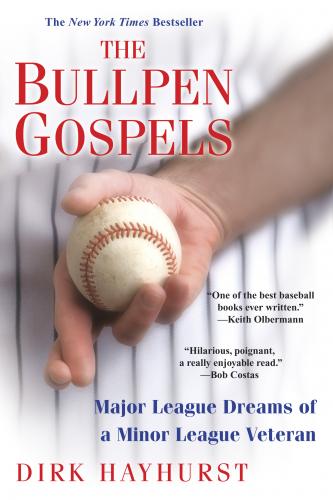

There is so much you don’t know when you get into the baseball business. You think you know it all. You’ve certainly seen enough of it on television to form an educated guess. But the stuff that happens on television isn’t real, no matter how bad you want it to be. I thought signing a contract to play was going to be my promotion into the glamour lifestyle. I would walk down the street and people would whisper, “There goes Dirk Hayhurst, professional baseball player.” Maybe they’d stop me for an autograph or ask me what it was like to be so awesome. I was going to live the big-league dream life. What the hell happened? Where were all the millions? Where were the luxury cars? Where was my first-class jet to paradise? Where was my dignity?

Instead, my career has crash-landed me on the floor of Grandma’s sewing room. If this is a dream come true, then dreams come packed in mothballs, smell like Bengay, and taste like lard-flavored turkey leg. My dream has made me into a commodity, a product, only as valuable as the string of numbers attached to my name—like some printout stuck in the window of a used car. The reality of my professional baseball player’s life is that most people have no idea who I am, nor do they care. The pay sucks, the travel sucks, the expectations suck, and, recently, I suck. Instead of gaining ground in life through my dream job, I’ve lost it. I’m further behind than when I started.

People always say they’d do anything to