made the world and everything in it . . . does not live in shrines made by human hands, nor is he served by human hands, as though he needed anything, since he himself gives to all mortals life and breath and all things. From one ancestor he made all nations to inhabit the whole earth, and he allotted the times of their existence and the boundaries of the places where they would live, so that they would search for God and perhaps grope for him and find him—though indeed he is not far from each one of us. For “In him we live and move and have our being”; as even some of your own poets have said, “For we too are [God’s] offspring.”

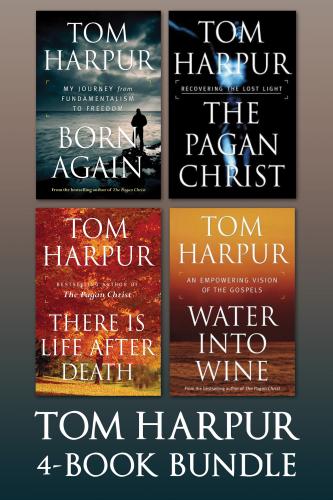

I wish to emphasize what the Pagan poets being referred to here (Cleanthes and Aratus) actually said because it struck me so forcibly at the time that this is precisely the core message of Christianity also! Every living human—being regardless of creed, colour, sexual orientation or status in society—is a child of God and lives, moves and has his or her being in God, the Ground and Source of all Being. I lay some stress upon this growing awareness of the universality of the Christian message because it played an important part as gradually, through the years of intellectual preparation for the studies and the ministry that lay ahead, I began to challenge little by little the narrower viewpoint of my early years. The discerning reader will already have noticed aspects of my thinking destined later to be fully defined in The Pagan Christ and in Water into Wine in particular.

The question of whether or not students in training for the ministry at Wycliffe College (where I was in residence while attending University College) would take a summer charge each year even while they were still in their general arts course was never seriously discussed. In 1948, at the end of my first year in Classics, the principal, Dr. Ramsay Armitage, one of the finest human beings I have ever known, simply called me into his office and told me of the assignment he wanted like me to undertake that summer. He told me to go upstairs to my room and “pray about it” and then come down to his office the next day to pick up the train tickets. He told me, “They’re expecting you next week.” Apparently no need to ask for divine guidance after all!

When I was still a choirboy, all decked out in an angelic white surplice and high starched collar, I used to sit in church during the sermon and fantasize about being a missionary in the High Arctic. The traditional cleric in his dark suit and Roman collar had minimal appeal for me. But I could see myself with the frost ringing my parka hood of wolverine fur, driving my tireless huskies across the vast expanses of snow in search of hapless Natives to whom I could do immeasurable “good” in some very vague, idealistic manner. Later I eagerly devoured books on the North, especially the one about the bishop who ate his boots—Bishop Stringer. In my reveries I elevated myself to the rank of northern prelate, complete with gaiters, flying my own plane into remote Eskimo communities where I would be met with applause and undying loyalty.

When I did finally arrive in the North as a student teacher that first summer, the reality was of course somewhat different from the dream. I was to be a schoolteacher to about seventy Cree children. Big Trout Lake reserve (or Kitchi Numaboos Seepik, as the Cree call it) was a huge expanse of primeval bush, rivers and lakes about 1,600 kilometres northwest of Toronto. It was very close to what today is known as the “Ring of Fire,” where vast mineral deposits are currently being prospected by a host of claimants. Chromium, a vital but rare element for the making of steel, is apparently hidden there in very large quantities. Diamonds of a quality equal to those of South Africa have also now been discovered not many miles from the reserve. At that time the Hudson Bay store held a monopoly on all sales there, and the Anglican Church had a monopoly on religion. The only non-Natives on the reserve at that time were the Anglican missionary, the Hudson Bay manager and his clerk, two weather station staff and myself. The Cree children lived with their trapper parents on their remote traplines for most of the year and came in just for the summers. Then they would fish, socialize and go to church almost every day. These children were not a part of the controversial residential school system and got their only formal education during the summer months.

With growing excitement I boarded the train at Union Station in downtown Toronto at midnight, settling into a lower berth and then watching through the window as the farmlands of southern Ontario gradually gave way to the rocks, lakes and pines of the Canadian Shield. I was just nineteen and off on the first real adventure of my life. I arrived in Sioux Lookout at eleven-thirty the following night to find the town in a fever over the recent discovery of gold close to the edge of the tiny community. Even the lawns on the main street had been staked out by prospectors, and, to my dismay, the only bed in town was a cot in the middle of an already full room in a very cheap hotel. I tried my best to sleep, but the snoring of one fellow in the corner and the fact that another’s boots kept up an irregular thumping on my head as their owner twisted and turned made it very difficult.

I had to spend nearly a week in Sioux Lookout because bad weather made it impossible for the Norseman float plane I was taking for the final 500-kilometre leg of the journey to attempt to fly. I spent most of my time reading or watching a couple of Chinese men catch pickerel in Pelican Rapids, just west of the town. It turned out they ran the best restaurant in town (there were only two), and I used to order the daily special at both lunch and supper. It was, of course, fresh pickerel, better than filet mignon any day by my reckoning.

With all that time on my hands, however, I was feeling pretty lonely and a little homesick. As in the army or on a film set, a lot of one’s time as a missionary is spent waiting. So it was with great relief that I finally received the message to get ready for departure in a couple of hours. Turning up at the dock with my duffle bag, I found the plane loaded with supplies of all kinds, including a couple of drums of gasoline, two or three outboard motors, several cases of liquor “for the boys at Round Lake” and three Indian children who had been waiting for over ten days to get a ride back to their parents’ after a fall and winter spent at the Sioux Lookout residential school.

The pilot, a former fighter pilot with the RCAF who reportedly had a problem with drink and eventually, having crashed his plane once too often, ended up driving a taxi in a small northern town, saw at once that we would never get off the water with such a load. So he ordered the three Cree children to get off and wait for some other flight. (Nobody knew when that might be.) He then rearranged some of the cases, sat me on a motor next to a reeking gas drum and gunned his engine. As we sped across the bay and the trees of the opposite shore rushed towards us, anyone could tell that we weren’t going to make it. At the last possible moment the pilot cut the power, cursed loudly and taxied back to his base. Here, at the small dock, he unloaded one or two bulky parcels (but not the booze) and asked me to lean over the cockpit for takeoff so as to get more weight forward. When we headed out again, my heart was in my mouth. As before, there was the furious roar as we picked up speed and shot out across the water. The pilot kept rocking the plane to help free it from the suction on the floats, and at the last second, when it seemed a crash was certain, he yanked the thing up and over the menacing border of pines. “We made it,” he said with a big grin. I was too weak even to agree.

It was a very bumpy flight, and as the air grew warmer and the fumes of the gasoline I was sitting beside became stronger, I began to feel very ill indeed. To make matters worse, my ears were blocked with the change in pressure. Just when I thought I couldn’t take it any longer, a small cluster of cabins and teepees appeared on the edge of a lake ahead, and in a few moments we had touched down at Cat Lake to discharge half of our cargo. The entire dock was crowded with Cree who had come to shake hands with anyone on board. My leg was seized in a viselike grip by a big husky dog putting the bite on me, and there were howls of laughter at my predicament. One man eventually released me, saying, “He’s just trying your leg out for size—he does that to every newcomer.”

After what seemed like an eternity, we took off again, and the pilot thrust a large, wrinkled