Clearly I have never forgotten those few words of a warm, gentle afternoon in the spring of 1954. They are deeply connected with the events of spring 2004, a half century later. From the very beginning it’s as though I already knew the wisdom of Robinson’s insight somewhere deep in my own unconscious mind. Though all through my childhood, youth and years of training for the ordained ministry of the Anglican Church I was a model of conformity, at the same time I was quietly questioning the major questions themselves. The tradition assumed a hubristic superiority over all other faiths. As I matured, I was silently asking myself, was it right that a white man’s saviour was the only mediator or redeemer of the many billions here on earth today? And what of the far greater number of billions making up “the majority,” as the Romans referred to them, those who have died over the entire span of Homo sapiens sapiens’ presence on the planet? Why did it take the Church five centuries—not to mention so much bloodshed—to work out its understanding of how Jesus could be wholly God and wholly man without rupturing the basic concept of a truly human humanity entirely? The struggle to make sense of this conundrum is clear in the words of the Athanasian Creed from the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, which says Jesus Christ is “God, of the Substance of the Father, begotten before the worlds: and Man, of the Substance of his Mother, born in the world; Perfect God, and perfect Man: of a reasonable soul and human flesh subsisting; Equal to the Father, as touching his Godhead: and inferior to the Father, as touching his Manhood. Who although he be God and Man: yet he is not two, but one Christ . . .” Based upon Greek philosophy, this makes little or no sense to the average person today.

What kind of religion, I later asked myself, would burn at the stake three of its own bishops in the city of Oxford (a short distance from my own college of Oriel) simply because they could not accept the dogma of transubstantiation, that is, that the symbols of bread and wine actually become Jesus’s body and blood in the Mass? Latimer and Ridley, the latter of whom was the Bishop of London, were burned alive in Oxford on October 16, 1555. Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury, was killed on March 21, 1556, for the same offence. The travesty is that, whatever its meaning, Holy Communion or Mass was meant to bring people together, to enhance life. It certainly has nothing to do with murder. Once again, mistaking symbols for facts had cost—and continues to cost—the Church dearly.

The following narrative tells of a quest for truth. Its goal is hopefully to bring more light. For me, it has been the spiritual journey of a lifetime.

2

BIRTHMARKS

ARE FOREVER

IN 1969, I did something that in my teens I’d never expected to do—reach my fortieth birthday. In a Byronic, Romantic mode, I had earlier seen myself as destined for a premature, no doubt spectacular demise in the midst of some high adventure. Reflecting on this development, I was aware that all of the major goals my parents, their friends and various clergy had set before me from the beginning had been reached. I was an ordained priest of the Anglican Church of Canada, a former Rhodes Scholar and hence a graduate of Oxford University as well as the University of Toronto, where I had graduated in 1951 with the gold medal in Classics. I was also a graduate of Wycliffe College, Canada’s evangelical Anglican seminary, and had been the class president and valedictorian in my graduating year. Furthermore, I had had a highly successful parish ministry for eight years, highlighted by the building of a beautiful new church to accommodate a large and growing congregation. I had left there in 1964, after another year of graduate studies at Oxford, to become an assistant and then a full professor of New Testament and Greek back at Wycliffe. I was in good health. So too were my then wife and three much-loved daughters. There was every reason for me to be happy with these successes. “They”—the proverbial and in part shadowy influences that too often one can attempt to live one’s life by—were happy. But I was not.

The truth is, I was profoundly miserable. At times I had a feeling of having arrived successfully at a defined destination after having taken the wrong boat. It seemed that I was reaching a major turning point. Deep inside I felt I was bursting with repressed creative energy, but at the same time I was baffled and uncertain about where to go with it. Although it was far from clear at the time, a process was beginning that would utterly transform me at every possible level. I was about to experience a radical series of changes that I now realize was a kind of second birth. It would lead eventually to a total transformation of my understanding of God, of the Christian religion, of human evolution, and of myself. What ensues is the story of how that came to be and of what it led to. Like all births, it happened in stages. Like most, it wasn’t always neat.

What follows, then, is not a memoir in the usual sense. It is a spiritual odyssey, the story of one individual’s escape from the narrow grip of a rigid, wrong-headed religion. Many who grew up in similar backgrounds have escaped as well, by abandoning their spirituality altogether. In my case the struggle was to hammer out a believable faith in God. Of course, by the traditional term God, I mean that transcendent, ever-present “presence” whose offspring, as the ancient Pagans also saw, we truly are. This is the great mysterium tremendum et fascinosum of Rudolph Otto—the Mystery that kindles in us both an overwhelming sense of awe and a heart-yearning desire that can never be satisfied with anything less.

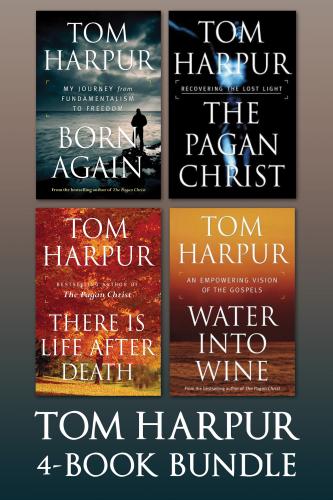

The question most often posed in the many hundreds of letters that have poured in over the past few years is this: “How did you come to the radical conclusions set out in 2004 in The Pagan Christ? You were once an evangelical preacher, weren’t you?” A partial answer is given at the beginning of that book. But the real answer, like most truths worth knowing, can only be fully told in a more detailed narrative. I invite you to come with me on this adventure.

While we all are born as genetic composites of previous generations, our ideas and outlook must of course grow and adapt to our ever-changing surroundings and intellectual development. Over the last fifty years and in the span of only two generations, beliefs and ideas in my own family have changed radically. Few could have predicted the extent of the change in the understanding of God and religion that I am about to describe. But I am fully aware in saying this of the truth of an aphorism attributed to Muhammad Ali: “The person who views the world at fifty the same as he did at twenty has wasted thirty years of his life.”

Both my parents were born and raised in Northern Ireland and came from fairly large families, with each of them having six siblings. My maternal grandfather, who always wore a wing collar and a black bowler hat for going to church and other dress occasions, served as an ambulance driver in World War I, and I vividly remember him telling how their convoy was attacked one night by bombs from a German dirigible or blimp and they all had to scramble for cover into a ditch, where they lay for several hours in the cold. He could be very kindly, but his basic demeanour was stern and forbidding. I first met him at the age of nine in 1938 on a visit to Belfast, and soon shared my cousins’ view that he was dangerous when provoked. Grandpa Hoey, as he was called, was definitely of the old school where discipline of children was concerned. Following the end of the war he was hired as chauffeur and gentleman’s gentleman by a wealthy Belfast industrialist. My grandmother’s family name was Cooper and they were from farming stock near Portadown on the coast. She was a jolly, comfortable-looking woman who loved nothing better than being up to her elbows making Irish soda bread.

My mother’s family had been Presbyterian for generations, and she too was raised in that somewhat unbending, rigorous mould. She grew up in Belfast when the Troubles were just beginning. She remembered swinging on the lamppost at the corner of her street with two or three other little girls while soldiers nearby crouched behind sandbags with an eye out for snipers. Tragically, one child on her street was killed when a soldier accidentally dropped his rifle and it fired. This incident made quite an impression on me when I first heard about it at the age of six or seven. It was at about the same age that I heard my father, who joined the Ulster special police at sixteen by lying about his age, describe some of the violence of that period, including an account of one night while on duty near a cinema in