Such is the makeup of the standard falca, the only way to navigate the central portion of this river. There is also a miniature dinghy, which the Indians call a curiare, which is used to maneuver the towline.

The skipper of these vessels is the man with whom travelers do their negotiating, and the charter fee is not based on how far you go but on how long the boat is in use. The agreed-upon fare is paid daily. No skipper would have it otherwise. The fact is, he faces many obstacles while sailing the Orinoco: surging waters, gusting winds, disruptive rapids, and the difficulty of carrying his boat around every unexpected obstacle that blocks the way. The whole trip can be done in three weeks, but it takes twice as long if weather conditions deteriorate. Consequently, no skipper will agree to carry passengers out of Caicara, neither to the mouth of the Meta nor to San Fernando, if he knows bad weather is coming. In this situation, it is best to bargain with the Banivas Indians, who placed a pair of falcas at the disposal of the travelers.

M. Miguel had the good luck to pick an excellent river pilot. He was a muscular, energetic, and intelligent Indian named Martos, around forty years of age and in full charge of his crew, nine well-built natives who were old pros with the palanca, garapato, and espilla. He set a steep price on this trip, it was true. But when it came to settling such an important matter as the Guaviare versus the Atabapo versus the Orinoco, it was no time to pinch pennies.

The geographer was inclined to think that Jean de Kermor and Sergeant Martial were just as lucky in their choice—nine Banivas also, supervised by a Spanish-Indian half-breed who came with good credentials. This half-breed was named Valdez,4 and if his passengers needed to continue beyond San Fernando into the upper reaches of the Orinoco (which he had already sailed in part), he was ready to stay on in their employ. But that issue would be settled later, after they had obtained information about the colonel in San Fernando.

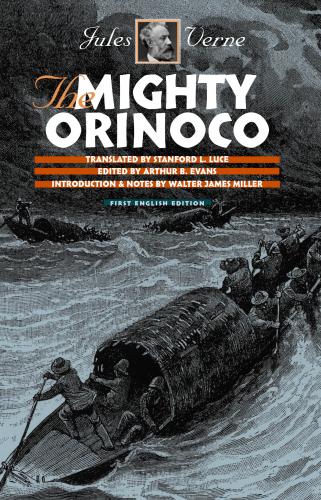

The two falcas had their own names. The craft containing MM. Miguel, Felipe, and Varinas was called the Maripare, after one of the Orinoco’s many islands. The one carrying Sergeant Martial and his nephew had been christened the Gallinetta, after another island. Topside both boats were white, while their hulls were black from stem to stern.

Needless to say, these vessels would travel as a twosome, neither one trying to outdistance the other—falcas are not Mississippi steamboats constantly racing to set new speed records.5 Besides, one must always watch out for hostile Indians from the riverside grasslands, and there is strength in numbers.

The Maripare and the Gallinetta could have set out that afternoon—the only thing left was to buy provisions. As for that, the shopkeepers of Caicara were all set to furnish the supplies one would need on a cruise of several weeks up to San Fernando, where one would be able to stock up again. They sold everything—canned food, clothing, ammunition, tackle for fishing and hunting—and were eager to do business, so long as the purchase price could be paid in piasters.

Of course, these Orinoco travelers could also count on the abundant game along the riverbanks and on the teeming fish of its waters. For one thing, M. Miguel was an expert hunter; for another, Sergeant Martial was a crack shot with his rifle. And in Jean de Kermor’s grip, even a small handgun could be very useful. But one cannot live by hunting and fishing alone; it is necessary to take along some sugar, cured meat, canned vegetables, flour extracted from cassava or manioc plants, which is a good substitute for flour from wheat or corn, plus a couple of kegs of rum and brandy. As for fuel, the riverside forests offer unlimited wood for the stoves on these boats. Finally, to cope with the cold, or rather the damp, it was no problem to buy some of those wool blankets that were on sale in every town in Venezuela.

These purchases took several days, but nobody minded the delay because, for forty-eight hours, the weather was especially bad. Caicara was struck by one of those exceptionally violent storms that the Indians call chubascos. It blew in from the southwest, with torrential rains that brought a noticeable rise in the river.

It gave Sergeant Martial and his nephew a preview of the difficulties of navigating on the Orinoco. Had they set out, the two falcas would neither have been able to go upriver against the swollen currents nor make any headway against those strong winds. Without the slightest doubt, they would have been forced back to Caicara, and maybe even been badly damaged.

MM. Miguel, Felipe, and Varinas were philosophical about this delay. It mattered little if their trip took a few weeks longer. By contrast, Sergeant Martial was in a vile mood; he grumbled, swore against the floodwaters, and cursed the storm in both French and Spanish, until Jean had to step in and calm him down.

“You’re a man of courage, my dear Martial,” the boy remonstrated, “but you must also be a man of patience! We’ll no doubt need much of the latter in the days to come!”

“I’ll be patient, Jean, but why is this accursed Orinoco treating us so badly at the beginning of our journey?”

“Look at it this way, uncle! If the river’s going to act up, isn’t it better now than later? Who knows, we might have to go all the way up to its source!”

“Yes, who knows!” Sergeant Martial muttered. “And who knows what may be in store for us there?”

During the day of the twentieth, the gale died down greatly as the wind shifted to the north. If it remained in that direction, the boats could be launched. At the same time the high waters began to recede, and the river returned to normal. The two skippers, Martos and Valdez, stated they could leave by midmorning on the next day.

And indeed they did depart under the most propitious circumstances. By ten o’clock the townspeople were down on the riverbank. Both falcas had Venezuelan flags flapping from the tips of their masts. Stationed in the bow of the Maripare, MM. Miguel, Felipe, and Varinas waved back to the cheering natives.

The Maripare and the Gallinetta

Then M. Miguel turned toward the Gallinetta. “Safe journey, Sergeant!” he called out heartily.

“Have a good trip, monsieur!” the old soldier answered. “Because if it’s good for you—”

“It’ll be good for us all!” M. Miguel chimed in. “Since we’re traveling in tandem!”

Barge poles shoved off from the bank, sails were hoisted up the mastheads, and the two boats were driven to midriver by a smart breeze, while the cheers soon faded behind them.

CHAPTER VI

Island after Island

Their trip along the central Orinoco was now under way. How many tedious hours, how many dreary days would go by aboard these falcas! And how slow their progress would be on this river that was so ill-suited for rapid travel! But of course it would not be tedious for M. Miguel and his friends. They could hardly wait to reach the junction of the Guaviare and Atabapo rivers, where they would carry out their geographers’ work. They would complete the hydrographic survey of the Orinoco, study the layout of its tributaries no less numerous than its islands, plot the exact locations of its rapids, and finally correct the errors still contained in the maps of these territories. For scholars on a quest for knowledge, time flies!

It was regrettable that Sergeant Martial had been so against them all traveling in the same boat, because the hours would have passed less slowly. But on this point the uncle had been absolutely adamant that this was their only choice, and the nephew had not objected.

So Jean had to settle for reading and rereading the work of M. Chaffanjon, as thorough and meticulous on every aspect of the Orinoco as he was. The young man could not have found a better guide than this French explorer.

Once the Maripare and the Gallinetta had reached midriver, one could see hills rising from the surface of the nearby plains. Toward eleven o’clock in the morning, a cluster of huts came into view