“Thank you, Mr. Governor,” he said. “Thank you for the interest you have in my uncle and me. You’re certain that you’ve never heard of Colonel de Kermor, but we are just as sure he visited San Fernando in April 1879. That is where his last letter was mailed from, and we received it in France.”

“What was he doing in San Fernando?” M. Miguel asked, a question that the governor had not yet raised.

Sergeant Martial gave him an ugly scowl and muttered between his teeth: “Now the other one’s butting in. What’s he trying to do?”

Jean nevertheless answered without hesitation, “I don’t know. That’s a mystery we hope to solve, if the good Lord allows us to catch up with him.”

“Then what’s the connection,” the governor asked, “between you and Colonel de Kermor?”

“He’s my father,” Jean answered. “I’m here in Venezuela to find my father.”4

CHAPTER V

The Maripare and the Gallinetta

Nestled in a bend of the river, Caicara could not have asked for a better location. Although four hundred kilometers upriver from the Orinoco delta, it is nevertheless situated like a roadside inn at a busy intersection, an excellent position for commercial success.

And Caicara is indeed prosperous, in part because of its proximity to the Apure, a tributary located just upstream that serves as a principal trade route between Colombia and Venezuela.

The Simón Bolívar reached this freshwater port around nine o’clock in the evening. Having left Las Bonitas at one o’clock in the afternoon, then sailing past the Cuchivero and Manapire rivers and then Taruma Island, she had just arrived and was dropping off her passengers at the Caicara loading dock.

These passengers, needless to say, were those whom the boat was not taking up the Apure to San Fernando or Nutrias.

Among them were the trio of geographers, Sergeant Martial and Jean de Kermor, and an assortment of other travelers. The next morning at sunrise, the Simón Bolívar would depart and sail up this major Orinoco tributary to the foothills of the Colombian Andes.

M. Miguel had not neglected to pass along to his two friends the additional information that Jean had supplied in his conversation with the governor. Both now knew that the young man had come in search of his father, under the wing of his so-called uncle, Sergeant Martial, the retired soldier. Fourteen years earlier, Colonel de Kermor had left France to come to Venezuela. As for the circumstances that caused him to leave his homeland and what he was doing in this distant country, only the future would perhaps reveal. All that was certain, according to a letter the colonel had written to a friend of his—a letter that came to light only years afterward—was that he had passed through San Fernando de Atabapo in April 1879, even though the Caura governor, who lived in that town back then, had no knowledge of his presence.

So, determined to track down his father, Jean de Kermor had made this difficult and dangerous trip. When a young man of seventeen undertook such a journey, no right-thinking person could fail to be sympathetic. MM. Miguel, Felipe, and Varinas swore to themselves that they would do everything they could to help him gather information about Colonel de Kermor.

The question was, would M. Miguel and his two colleagues be able to get around that cranky Sergeant Martial? Would the sergeant let them get to know his nephew better? Could they overcome the NCO’s strange distrust of others? Could they tame this watchdog whose growling kept everybody away? It would be tricky, but maybe they could manage it, especially since the same boat would be taking them all up to San Fernando together.

Caicara has a population of about five hundred people and is often visited by traveling merchants who do business along the upper Orinoco. There are a couple of rooming houses in town (more accurately, rooming huts), and the five travelers decided to stay in one of these—the three Venezuelans on one side and the two Frenchmen on the other—for the few days they were to remain in this locality.

The next morning, August 16, Sergeant Martial and Jean toured Caicara, looking for a boat.

It is true that Caicara is a bright and cheerful little town, snuggled between the lower slopes of the Parima range and the right bank of the river, facing the village of Cabruta on the opposite bank by the mouth of the Apurito. Before it stretches one of those lushly wooded islands that are so common in the Orinoco. Its tiny harbor is located among the black granite rocks that adorn the river’s course. The town consists of about one hundred and fifty huts (or houses, if you prefer), most of which are built of stone with roofs of palm branches or red tile, whose color stands out from the surrounding greenery. Overlooking the town is a knoll some fifty meters high. On its summit stands a mission monastery, abandoned after Miranda’s expedition and the struggle for independence, and which was once desecrated by the cannibalistic practices of the Carib Indians whose bloodthirsty reputation is thoroughly deserved.1

Moreover, time-honored Indian customs are still in use in Caicara, as well as those that mix Christianity with unusual religious rituals. For instance, there is the custom of the velorio, a watch over the dead, a vigil which the French explorer once had a chance to attend. The many participants therein consume extravagant amounts of coffee, tobacco, and above all brandy in the presence of the body of the husband or child. The wife or mother initiates the dance which only stops when the dancers, drunk and exhausted, can continue no longer. It is more a dance festival than a funeral.2

Meanwhile, the first problem Jean de Kermor and Sergeant Martial had to solve was chartering a boat to go up the central portion of the Orinoco, a run of about eight hundred kilometers from Caicara to San Fernando. This was likewise the foremost concern of MM. Miguel, Felipe, and Varinas. To M. Miguel was given the task of securing transportation under the most favorable terms.

Understandably, M. Miguel thought that if he and Sergeant Martial agreed to go in together on this, it would simplify matters considerably. It made no difference whether the travelers numbered three or five—a single boat could easily hold them, and no additional crew would be needed.

Recruiting such boatmen, however, is not always easy. One must hire experienced men. During the rainy season these dugout canoes have to sail against the wind much of the time and against the current all of the time. There are plenty of dangerous rapids as well as channels clogged with rocks or sand, which require long portages along the riverbank. Just like the ocean, the Orinoco has its whims and bad moods, and nobody can travel it without certain risks and perils.

It is customary to search for boatmen among the riverside tribes. With many of these natives, it is their only line of work and they have learned to do it with great skill and courage. Among the most capable, it is said, are the Banivas Indians, whose clans live mainly in the lands located near the Guaviare, Orinoco, and Atabapo. After taking passengers or freight upriver, they usually come back down as far as Caicara to wait for new travelers and cargo.

Are these boatmen trustworthy? The fact is, not very. It would thus be safer to recruit only one crew, M. Miguel correctly reasoned. Besides, since he was deeply interested in Jean’s welfare, the young man could only benefit from having the geographer and his two friends as traveling companions.

With this idea in mind, he decided to discuss the proposition with Sergeant Martial. And, when he spotted them down at Caicara’s little harbor where the sergeant and Jean were inquiring about a boat to hire, he immediately approached them.

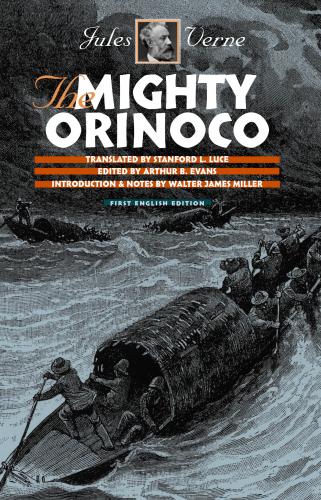

Searching for a falca to hire in Caicara

The old soldier was frowning, and his attitude toward the geographer anything but neighborly.

“Sergeant,”