All this sounds quite serious. And in a way it was. I was intense and determined but also floating in an often-turbulent sea of mixed emotions. I don’t think I was bipolar or depressed or schizophrenic or any such thing. I think I was normal enough, but in a time of expanded consciousness we were looking at the world in new and different ways.

Then there was also the psychedelic experience. Kenny’s mother, Gladys, was a psychoanalyst. She had a strength and curiosity and vitality that I absolutely loved. Her kids had an assurance and sense of humor about themselves that was way ahead of most of the people back home. Simply put, it was sophistication. As an analyst, Gladys was in on the latest lectures and symposiums and talks related to her field. So, she got an invitation for a session with Timothy Leary. She couldn’t go to this one, so Kenny and I went in her place. I think Leary may still have been teaching at Harvard or was about to be fired—and Alan Watts was there too. Leary’s book The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead had recently been published and I guess the idea behind these simulated “experiences” was to further legitimize their passion for LSD and its therapeutic potential.

The day came for our “trip” and we went to one of the most beautiful town houses I’d ever seen. It was on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, between Madison and Fifth Avenues. A truly elegant building with a carved entry and wrought iron railings with a barred doorway. We were led to a ground-floor room, where a small circle of people were sitting on the carpet. Leary was explaining the chakras and the stages of the experiment and encouraged us to relax and go with it. There were no drugs, no drinks, no food, only suggestions and directions about what this LSD trip could be like. In fact, it was based on a spiritual journey through different states of consciousness, known as the bardo.

At this time, Leary’s ideas were breathtakingly new and he had gotten some really dicey press about his teachings and drug use. We sat in the circle with the others and listened to Timothy chanting and speaking, guiding us through what might have been a mind expansion—if we could let ourselves go with it. Well, Kenny and I both were curious and wanted to learn something, so we hung in with the lecture. It went on forever and I was hoping there would be a snack at some point, but no such luck. We sat there for hours while Professor Leary and Alan Watts spoke about these levels of the mind. Finally we were all asked to interview each other.

There were all kinds of people there that day, not just hipsters or students. All kinds of businessmen and women; doctors, local and foreign; some nicely dressed uptown types; a few art-world people from the neighborhood; and analysts, of course. There was one man who made me nervous because he just radiated resistance. He held himself apart as if simply observing. He wore a white business shirt and dark gray trousers. He was balding and clean-cut. Of course, I was put opposite him for the interviews—the “getting to know you” part of the afternoon. I was uptight, not nice at all, and starving by then. So, I had it in for this poor man from the get-go and quizzed him in a way that he wasn’t expecting. It turned out he was there in some official capacity from either the CIA or the FBI. Which came as a jolt to Leary . . .

Kenny’s father was interesting too. He had a company called Dura-Gloss that made nail polish. A brand that my mother used. I used to love the little bottles it came in. It seemed a bit synchronistic that I should be seeing this guy. My mother must have thought so too, because she was putting the screws on Kenny to get serious. I thought he was great, but I wanted to experience what the world was and find out who I was before settling down. I think he did too. He went on to get his master’s degree and in a way I did too, eventually.

Me, I graduated with an associate of arts degree. I found a job in New York, but I couldn’t live there, I had no money, so I commuted back and forth, which I hated. I spent hours looking for an apartment in the city, but I couldn’t find anything remotely affordable. I guess I was moaning about it to my boss Maria Keffore at work. Maria, who was a very pretty Ukrainian woman, said, “Oh, you don’t have to worry. Come see my apartment. The rent is only seventy dollars a month.” OH MY GOD, how can it be so cheap, I thought, what must it be like? Well, it was fantastic. It was on the Lower East Side, which was a Ukrainian and Italian neighborhood at that time, and under rent control.

With Maria’s help I found an apartment with four rooms for just $67 on St. Mark’s Place. That first night in my new home, lying on the bed listening to the sounds of the street floating through my window, I felt like I was finally, twenty years into my life, in the place where my next life would begin.

They used to say I looked European.

Childhood and family photos, courtesy of the Harry family

Sean Pryor

Dennis McGuire

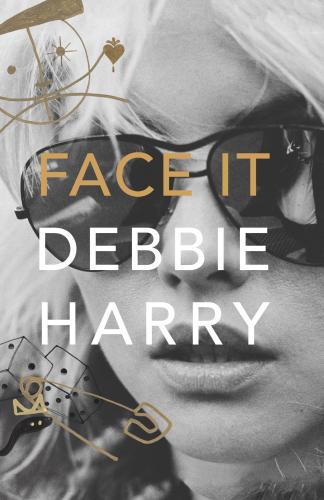

I hated my looks as a kid but couldn’t stop staring. Maybe there were one or two pictures that I liked, but that’s all. For me, capturing those looks on film was a horrible experience. Eventually the peeping, secretive, naughty aspect of it made being photographed all right, but voyeurism was not part of my vocabulary as yet. How could I know then that this face would help make Blondie into a highly recognizable rock band?

Does a photograph steal your soul? Were the aboriginal people right? Are photographs part of some mystical image bank, a type of visual Akashic record? A source of forensic evidence to examine the hidden, darker secrets of our souls, perhaps? Now, I can tell you that I’ve had my picture taken thousands of times. That’s a lot of theft and a lot of forensics. Sometimes I read things into those pictures that no one else seems to see. Just a tiny glimpse of my soul maybe, a passing reflection on a piece of glass . . . If you were me, by now you might be wondering if you had any soul left at all. Well, I had one of those Kirlian photographs taken once at a new age fair—and there supposedly was my soul, my aura, staring back at me. Yes, maybe there is still some of my soul to go around.

I was working in an almost soulless place: a wholesale housewares market at 225 Fifth Avenue, a huge building full of everything you can think of that had to do with housewares. My job was selling candles and mugs to buyers from the boutiques and department stores. This had not been part of the dream. I started thinking that since I was pretty—well, my high school yearbook had named me Best-Looking Girl—maybe I could get some modeling work. I’d met two photographers, Paul Weller and Steve Schlesinger, who did catalog work and paperback book covers, and I decided I would make a portfolio. My modeling book had shots running from hairstyles to yogic poses in a black leotard. What was I thinking? What kind of jobs could I possibly get with these weird photographs? Answer: one and done.

Then I saw a blind ad in the New York Times looking for a secretary. It turned out to be for the British Broadcasting Corporation. This was my first link to what would become a long, lovely relationship with Great Britain. They gave me the job on the strength of the sensational letter that my uncle helped me write. Once they had me, they realized that I wasn’t very good at what I was supposed to do, but they kept me anyway and I grew into the job. I learned to operate a telex machine. I also met some interesting people—Alistair Cooke, Malcolm Muggeridge, Susannah York—who came into the office/studio for radio interviews.

Plus, I met Muhammad Ali. Well, not exactly met him. “Cassius Clay is coming in to do a TV interview,” they said, so I snuck around the corner and wow, I saw this big, beautiful man walk into the TV studio and close the door. It was a soundproofed room with a small window way up high, so I decided, being athletic, that I was going to grab the windowsill and pull myself up and watch the taping. But, as I pulled myself up, my feet kicked