Mom anxiously took me from Poppy and I clutched hard to her shoulder, my heart beating wildly from an unidentified terror. She carried me out onto the front porch, stroking my hair and hushing me. “No, you’re not,” she crooned just loud enough so only she and I could hear. “No, you’re not.”

Dad slapped open the screen door and came out on the porch as if to argue with her. Mom turned away from him and I saw his eyes, usually a bright hard blue, soften into liquid blots. I snuggled my face into her neck while Mom continued to rock and hold me, still singing her quietly insistent song: No, you’re not. No, you’re not. All through my growing-up years, she kept singing it, one way or the other. It was only when I was in high school and began to build my rockets that I finally understood why.

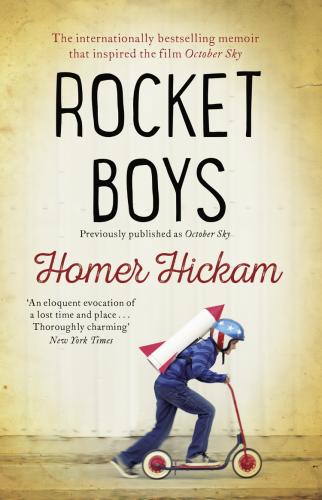

I WAS ELEVEN years old when the Captain retired and my father took his position. The Captain’s house, a big, barnlike wood-frame structure, and the closest house in Coalwood to the tipple, became our house. I liked the move because for the first time I didn’t have to share a room with Jim, who never made any pretense of liking me or wanting me around. From my earliest memory, it was clear my brother blamed me for the tension that always seemed to exist between our parents. There may have been a kernel of truth to his charge. The story I heard from Mom was that Dad wanted a daughter, and when I came along he was so clearly disappointed, and said so in such certain terms, she retaliated by naming me after him: Homer Hadley Hickam, Junior. Whether that incident caused all their other arguments that followed, I couldn’t say. All I knew was that their discontent had left me with a heavy name. Fortunately, Mom started calling me “Sunny” right away because, she said, I was a happy child. So did everybody else, although my first-grade teacher changed the spelling to the more masculine “Sonny.”

Mr. McDuff, the mine carpenter, built me a desk and some bookshelves for my new room, and I stocked them with science-fiction books and model airplanes. I could happily spend hours alone in my room.

In the fall of 1957, after nine years of classes in the Coalwood School, I went across the mountains to Big Creek, the district high school, for the tenth through the twelfth grade. Except for having to get up to catch the school bus at six-thirty in the morning, I liked high school right off. There were kids there from all the little towns in the district, and I started making lots of new friends, although my core group remained my buddies from Coalwood: Roy Lee, Sherman, and O’Dell.

I guess it’s fair to say there were two distinct phases to my life in West Virginia: everything that happened before October 5, 1957 and everything that happened afterward. My mother woke me early that morning, a Saturday, and said I had better get downstairs and listen to the radio. “What is it?” I mumbled from beneath the warm covers. High in the mountains, Coalwood could be a damp, cold place even in the early fall, and I would have been happy to stay there for another couple of hours, at least.

“Come listen,” she said with some urgency in her voice. I peeked at her from beneath the covers. One look at her worried frown and I knew I’d better do what she said, and fast.

I threw on my clothes and went downstairs to the kitchen, where hot chocolate and buttered toast waited for me on the counter. There was only one radio station we could pick up in the morning, WELC in Welch. Usually, the only thing WELC played that early was one record dedication after the other for us high-school kids. Jim, a year ahead of me and a football star, usually got several dedications every day from admiring girls. But instead of rock and roll, what I heard on the radio was a steady beep-beep-beep sound. Then the announcer said the tone was coming from something called Sputnik. It was Russian and it was in space. Mom looked from the radio to me. “What is this thing, Sonny?”

I knew exactly what it was. All the science-fiction books and Dad’s magazines I’d read over the years put me in good stead to answer. “It’s a space satellite,” I explained. “We were supposed to launch one this year too. I can’t believe the Russians beat us to it!”

She looked at me over the rim of her coffee cup. “What does it do?”

“It orbits around the world. Like the moon, only closer. It’s got science stuff in it, measures things like how cold or hot it is in space. That’s what ours was supposed to do, anyway.”

“Will it fly over America?”

I wasn’t certain about that. “I guess,” I said.

Mom shook her head. “If it does, it’s going to upset your dad, no end.”

I knew that was the truth. As rock-ribbed a Republican as ever was allowed to take a breath in West Virginia, my father detested the Russian Communists, although, it should be said, not quite as much as certain American politicians. For Dad, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was the Antichrist, Harry Truman the vice-Antichrist, and UMWA chief John L. Lewis was Lucifer himself. I’d heard Dad list all their deficiencies as human beings whenever my Uncle Ken—Mom’s brother—came to visit. Uncle Ken was a big Democrat, like his father. Uncle Ken said his daddy would’ve voted for our dog Dandy before he’d have voted for a Republican. Dad said he’d do the same before casting a ballot for a Democrat. Dandy was a pretty popular politician at our house.

All day Saturday, the radio announcements continued about the Russian Sputnik. It seemed like each time there was news, the announcer was more excited and worried about it. There was some talk as to whether there were cameras on board, looking down at the United States, and I heard one newscaster wonder out loud if maybe an atomic bomb might be aboard. Dad was working at the mine all day, so I didn’t get to hear his opinion on what was happening. I was already in bed by the time he got home, and on Sunday, he was up and gone to the mine before the sun was up. According to Mom, there was some kind of problem with one of the continuous miners. Some big rock had fallen on it. At church, Reverend Lanier had nothing to say about the Russians or Sputnik during his sermon. Talk on the church steps afterward was mostly about the football team and its undefeated season. It was taking awhile for Sputnik to sink in, at least in Coalwood.

By Monday morning, almost every word on the radio was about Sputnik. Johnny Villani kept playing the beeping sound over and over. He talked directly to students “across McDowell County” about how we’d better study harder to “catch up with the Russians.” It seemed as if he thought if he played us his usual rock and roll, we might get even farther behind the Russian kids. While I listened to the beeping, I had this mental image of Russian high-school kids lifting the Sputnik and putting it in place on top of a big, sleek rocket. I envied them and wondered how it was they were so smart. “I figure you’ve got about five minutes or you’re going to miss your bus,” Mom pointed out, breaking my thinking spell.

I gulped down my hot chocolate and dashed up the steps past Jim coming down. Not surprisingly, Jim had every golden hair on his head in place, the peroxide curl in front just so, the result of an hour of careful primping in front of the medicine-chest mirror in the only bathroom in the house. He was wearing his green and white football letter jacket and also a new button-down pink and black shirt (collar turned up), pegged chino pants with a buckle in the back, polished penny loafers, and pink socks. Jim was the best-dressed boy in school. One time when Mom got Jim’s bills from the men’s stores in Welch, she said my brother must have been dropped off by mistake by vacationing Rockefellers. In contrast, I was wearing a plaid flannel shirt, the same pair of cotton pants I’d worn to school all the previous week, and scuffed leather shoes, the ones I’d worn the day before playing around the creek behind the house. Jim and I said nothing as we passed on the stairs. There was nothing to say. I would tell people some years later that I was raised an only child and so was my brother.

This is not to say Jim and I didn’t have a history. From the first day I could remember being alive, he and I had brawled. Although I was smaller, I was sneakier, and we had