Chapter 3

Falling

Galactic cannibals

Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity

Chapter 4

Destiny

The life cycle of the Universe

Searchable Terms

Picture credits

Acknowledgements

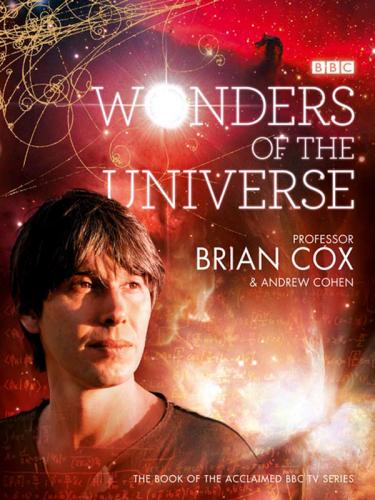

About the Author

Credits

INTRODUCTION

THE UNIVERSE

At 13.7 billion years old, 45 billion light years across and filled with 100 billion galaxies – each containing hundreds of billions of stars – the Universe as revealed by modern science is humbling in scale and dazzling in beauty. But, paradoxically, as our knowledge of the Universe has expanded, so the division between us and the cosmos has melted away. The Universe may turn out to be infinite in extent and full of alien worlds beyond imagination, but current scientific thinking suggests that we need it all in order to exist. Without the stars, there would be no ingredients to build us; without the Universe’s great age, there would be no time for the stars to perform their alchemy. The Universe cannot be old without being vast; there may be no waste or redundancy in this potentially infinite arena if there are to be observers present to gaze upon its wonders.

The story of the Universe is therefore our story; tracing our origins back beyond the dawn of man, beyond the origin of life on Earth, and even beyond the formation of Earth itself; back to events – perhaps inevitable, perhaps chance ones – that occurred less than a billionth of a second after the Universe began.

AN ANCIENT WONDER

On Christmas Eve 1968, Apollo 8 passed into the darkness behind the Moon, and Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and William Anders became the first humans in history to lose sight of Earth. When they emerged from the Lunar shadow, they saw a crescent Earth rising against the blackness of space and chose to broadcast a creation story to the people of their home planet. A quarter of a million miles from home, lunar module pilot William Anders began:

‘We are now approaching lunar sunrise and, for all the people back on Earth, the crew of Apollo 8 has a message that we would like to send to you.

In the beginning God created the heaven and the Earth.

And the Earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.

And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.

And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.’

The emergence of light from darkness is central to the creation mythologies of many cultures. The Universe begins as a void; the Maori called it Te Kore, the Greeks Chaos. The Egyptians saw the time before creation as an infinite, fathomless ocean out of which the land and the gods emerged. In some cultures, God is eternal: He created the Universe out of nothing and will outlast it. In others, such as some Hindu traditions, a vast primordial ocean predates the heavens and Earth. Lord Vishnu floated, asleep, on the ocean, entwined in the coils of a giant cobra, and only when light appeared and the darkness was banished did he awake and command the creation of the world.

We still don’t know how the Universe began, but we do have very strong evidence that something interesting happened 13.75 billion years ago that can be interpreted as the beginning of our universe. We call it the Big Bang. (We must be careful with our choice of words here, because this is a book about science, and the key to good science is the separation of the known from the unknown.) This interesting thing that happened corresponds to the origin of everything we can now see in the skies. All the ingredients required to build the