So Arden kept her counsel, and stored the little nuisance in a mental glory box of accumulated offences.

Mr Justinian steered her back towards the main street with its row of trestles while maintaining his lecture.

‘… the worst of the reprobates operate out of that establishment and upon these streets. See? This is why I have kept you in the safety of the Manse all this time, despite your obvious lack of gratitude. I have saved you from the worst outcomes that occur when men gather.’

‘They rather seemed more concerned with their own arrangements,’ Arden said, pulling away from him, and gladly so, for the Coastmaster’s hands were never content to rest upon her middle and had the unfortunate habit of crawling up towards the undersides of her bosom or the smallest part of her back. ‘My standing there was completely accidental.’

‘Oh, so you think yourself lucky for having escaped their attention?’ Mr Justinian said mulishly.

‘I do, in fact.’

He picked at the ruined sleeve of her coat. ‘Go buy a replacement for your torn coat and charge it to the Guild. Then we can leave this place. But don’t wander.’

I’ll wander off however I like, you insipid creature, Arden thought ferociously, her anger a physical pain that could not be soothed by her speaking the curse aloud, so remained inside her like a swallowed coal that did not cease to burn.

Arden picked in despondent indecision at the mess of fisherman’s clothing with gloves too fine for a village on the edge of nowhere, until her arms smelled of fishwax and linseed oil.

She had wasted so much time shut inside Mr Justinian’s decaying baronial estate, and at her first breath of liberty all she’d been allowed to see were street-fights and offal sellers. Despair – always so close and so suffocating – had fermented in her time under curfew. She had heard the domestic staff talk behind closed doors or under stairs. To them, Arden Beacon was not a professional guildswoman sent from the great ports of Clay Portside. She was merely produce fatted up for the eventuality of Mr Justinian’s bed.

‘A devil’s curse upon you, Mr Justinian,’ she said beneath her breath, tossing aside a scale-speckled pair of trousers, ‘and curse you, Mr Lindsay, for—’

The bronze flash caught her by surprise, stopped at once the bleak train of her thoughts. What imagination was that, her seeing such a thing in all these stained linens and thistle-cottons?

Arden dug in deep again and disinterred her find – an odd, slightly sheened garment – out from the knot of unwashed rags.

She raised to the day a thing that in her hands made no sense.

A coat. A stout, utilitarian coat cut for a female worker of hard ocean climates. Not too long in the hem though; no loose fabric to foul a hurried journey up stone steps in a high storm. A thing rightly made of old canvas and felted wool, worn on a body until it fell to pieces.

But the fabric …

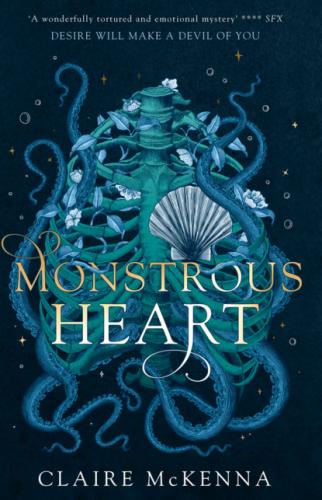

Arden had to rub the collar with her fingers, make certain her earlier fall was not causing her to see wonders. There was only one creature alive that could supply such a hide. Leather as bright as an idol’s polished head and with a crust of luminescent cobalt-blue rings across the arms and yoke. Subtle grading to black when it hit the light just so.

She turned the coat around and her breath caught. She had not expected the fabled kraken crucifix, the terrifying pattern of a sea-monster’s crest. By all the devils of sky and blood, you’d have found its likeness only in a Djenne prince’s wardrobe in Timbuktu, not a filthy rag pile at the edge of the world, and yet here it was; hidden away with thrice-mended broadcloth trousers and sweaters that were more knots than knits.

Before Arden could inquire about the article, her benefactor already had his hand about the coat’s collar.

‘Let me put that aside for you,’ Mr Justinian said and, without asking, slid in between her and the table, ready to yank Arden’s prize away. ‘This is not suitable.’

Despite her relatively short stature, and the dark, fragile air of over-breeding about her, Arden was no pushover. Growing up within the labyrinthine map of the capital city docks, one learned in the hardest of ways those streetwise traits anybody needed to survive. She saw the snatch coming in Mr Justinian’s beady eyes before he made his move, and quickly secured the coat within her strong lantern-turner’s hands.

‘No, Mr Justinian. I wish to buy it for myself.’

‘These wares are filthy. Look at them. Fish-guts and giblets. You are required to own a new coat to work the lighthouse, not cast-offs. As Coastmaster of Vigil I will have a fine plesiosaur leather coat made for you and sent from Clay Capital.’

‘I am not fulfilling your list by this purchase, Coastmaster Justinian. This coat is for my –’ she doubled down on her grip ‘– personal use.’

‘I’m telling you, you do not want it!’

He yanked harder, with enough force to pull Arden off her feet had the trestle corner not caught her thigh. She wedged herself deep into the splintering wood and hung on for grim life. Her ribcage groaned from the earlier trauma, sent sharp currents of pain through her chest, but still she held on.

‘No.’

‘Let … it …’

‘No, sir, no!’

They struggled for a while in stalemate, before he gave in with a hissed curse.

‘Keep the disgusting thing if you must,’ he said, tossing his end of the coat down. Arden heard the snarl under his disdainful words. ‘It is only a murdered whore’s garment anyway.’

‘A whore clothed herself in this rag,’ he concluded with caustic passion. ‘A bitch who lay down with an animal and got herself killed for it.’

His curse words spoken, and with God having not struck him from the face of the earth for saying them, Mr Justinian shoved the trestle table once for emphasis, then stalked off across the town square towards the Black Rosette.

Arden exhaled, prickling with both triumph and remorse. She had won something over Mr Justinian, but at what cost?

The jumble seller, a stout grey-haired woman with the pale vulpine features of a Fictish native, remained cheery in the face of Arden’s dismissal.

‘You’ll get used to the muck and bother here, love. Once our Coastmaster gets a pint of rot into him, all will be back to normal.’

‘I must apologize,’ Arden said with forced brightness to the jumble seller. ‘Ours was not a disagreement we should have made you witness to.’

‘The young Baron is correct about the krakenskin, I’m afraid.’ The woman shook the violet threads of ragfish intestines off a pair of trousers that looked identical to the ones she herself wore. ‘The coat is a cast-off and completely unsuitable for any purpose.’

‘But it’s hardly used. I need a wet-coat to work the lighthouse. Only krakenskin could reliably stand all the weather that the ocean might throw at it.’

‘The lighthouse? You mean Jorgen’s lighthouse?’ The woman shifted her now-nervous attention over Arden’s shoulder. The horizon behind the town was mostly obscured by fog, but a good five or ten miles away as the crow flew the