When my stepdad mentioned to Jack that I was too young for the job, Jack said he would make another call to his friend. I got a call later that day from Jack telling me to go back to the USFS office and try again.

I returned the next day to the same office in the Forest Service building. Before long, the same gentleman came in and introduced himself again and said, “Well, hello, young man. What can we do for you today?” I told him that I would really appreciate a job with the Forest Service.

He smiled and said, “Well, you look like the kind of young man that would do well in the Forest Service, and what’s your name?”

I told him my name again. “And how old are you, Gene?”

I replied, “I’m eighteen, sir.”

He said, “You just made the age cut. Here, fill out this application.”

And that’s how I became a firefighter for the Ellensburg Ranger District Fire-Suppression Crew based at the Liberty Guard Station, where they fought fire for the flag, God, and country. The guard station was located about thirty miles from Ellensburg, Washington, on Blewett Pass.

I know it sounds rather trite compared to today’s USFS firefighting policies, but our purpose during this period of time was to put out fires and save as much forest as we could as quickly as we could. Sounds like a rather strange mission statement by today’s USFS standards.

The Liberty Guard Station living facilities for our suppression crew in 1955 was rather quaint by today’s standards. We had a bunkhouse, an outhouse, a large equipment storage building and a small cook house. Our bathhouse was a small stream that flowed behind our bunkhouse. We had to supply our own soap, although we did have toilet paper in the outhouse once in a while.

When our suppression crew was without a fire to fight, we would keep busy learning how to sharpen a Pulaski or hoe with a circular sharpening wheel, which we turned by hand; or we would paint and repaint Forest Service buildings around the district. We did everything except feed the mules and load alfalfa bales on the wagon. Although a couple of years later at the Intercity Smokejumper Base, we did feed mules and buck bails!

On occasions, the suppression crew would patrol roadside firebreaks, which the Washington Department of Transportation would create as a fire barrier next to highways to protect travelers. One such firebreak patrol was on a stretch of highway between Wenatchee and Entiat. The temperature was several degrees above one hundred, and a couple of our crew spent time in the shade of our USFS crew transport truck with red faces and wet towels over their heads. We were even too tired to wave at the high school girls driving past on their way to Lake Chelan to sunbath and rub cocoa butter on each other.

I’m sure that if today someone saw potential sunstroke victims convalescing under a truck on a hot day, a USFS and Washington State board of inquiry would be called and someone of lower rank would be executed.

1955 Liberty Fire-Suppression Crew

The next day, the crew all agreed that we would rather hike ten miles into a fire and spend two days putting it out with an extra day of mop-up instead of another firebreak patrol in one-hundred-plus weather.

One day, we got a fire call. We quickly loaded up and set out for the fire. It was high up in the Cascade Mountains out of Leavenworth. It was a long twelve-mile hike up a steep trail to reach the fire. We had to wait several times for a couple of stragglers to catch up, and our WWII canteens were mostly empty when we got close enough to smell smoke. But when we got to the fire, I couldn’t believe my eyes. Some guys had beat us to the fire. They had funny little hard hats and canvas coats with a high collar in back. They sat beside the trail up on a bank and just stared at us as we struggled up the trail. No “How you doing guys?” no smiles, just that stare.

I said to a friend behind me, “Who the hell are these guys?”

He replied, “Smokejumpers.”

I said, “What’s that?”

He said, “They jump out of airplanes with parachutes and fight fires.”

I thought to myself these guys are spoiled rotten. No twelve-mile hikes uphill to fight fire, just a one-way trip. But on second thought, smart might be a better word.

So I asked one of these Smokejumper guys, “Where do I go to sign up to be a Smokejumper?”

He said, “Do you know where Winthrop is?”

Well, in late 1956, I found Winthrop Intercity Airport and a tough-looking guy named Francis Lufkin. I figured I would make the grade as a Smokejumper, I knew how to fight fire, and I had been practicing my badass sneer and expressionless stare for many months.

I spent the summer of 1956 working at a lumber supply company in Wenatchee. I had taken this job, which would allow me to be a volunteer summer football coach for my brother’s Eastmont High School football team. We met three times a week after work, and I taught the young ballplayers some of the game’s fundamentals. I enjoyed working with these young men, but I was very anxious to pursue my dream of becoming a Smokejumper during my summers as I continued to attend college.

In late 1956, I traveled up the Methow Valley following the Methow River to the Intercity Airport, which is located midway between Twisp and Winthrop. Certainly not an airport by the usual standards, just a long gravel runway and a group of USFS buildings; this facility was the home of the Smokejumpers. The base consisted of five buildings, a cookhouse, a bunkhouse, a recreation hall, which also served as our classroom, a bath house, the parachute loft, and the administration office or the Ad Shack Years. Later, this base would be called North Cascades Smokejumper Base.

I met with Francis Lufkin, the aerial project officer, and after an employment interview, Mr. Lufkin said that with my firefighting experience and apparent athleticism, I had a good chance of becoming a Smokejumper. I was one hell of a happy young man. My dream of becoming a Smokejumper was about to become a reality.

Francis Lufkin impressed me an honest, tough, no-nonsense kind of man. In 1939, he was one of the original Smokejumpers. He reminded me of my junior college football coach, Don Coryell. Rather than disappoint either of them, I would jump with no chute.

June 1957 finally arrived, and I reported for duty at the Intercity Smokejumper base along with twenty-one other young men. The 1957 group of rookie jumpers came from several towns, large and small, Winthrop, Twisp, Seattle, Cle Elum, Omak, and Joplin, Missouri. Three of our group were military veterans, and one of us, Ken Sisler, would later be awarded the Medal of Honor for his valor and bravery in Vietnam. Another of our class of rookies, Bill Moody, would become a base manager of NCSB. Others of our group would last out the summer, go through the long hours of training, make seven practice jumps, several fire jumps, and then never be seen again.

I soon fell into the training routine of becoming a Smokejumper: calisthenics, obstacle course, and a variety of jump classes such as first aid, fire behavior, chute manipulation, and practice jumping from the jump tower. It would take over two weeks of training before we were ready for our practice jumps.

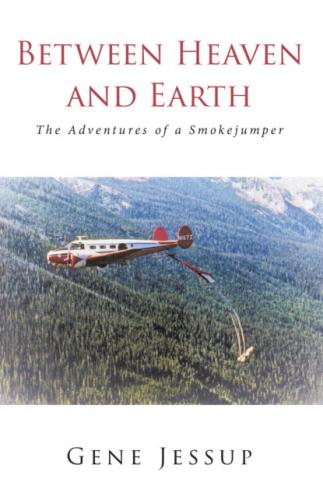

In 1957, the jump plane at NCSB was the Noorduyn Norseman. It was manufactured by the Noorduyn Aviation Limited of Montreal, Canada, from 1935 until 1959. The Norseman was designed to be used in the rugged Canadian forests as a utility transport. It was used as a training aircraft by the Royal Canadian Air Force prior to World War II. It also saw service in the USAAF during the war.

As a rookie jumper in 1957, I was introduced to the Noorduyn along with twenty-one other rookie jumpers on our first day on the job. Squad leaders informed us of the sterling qualities of this aircraft. We were told it was dependable and, like a good Marine, “always faithful.”

Noorduyn Norseman

We were later