The New Testament, for example, talks of heavenly liturgies, bodies that are but spirit and an angelic, celibate lifestyle in the hereafter. In the same theocentric vein, St Augustine spoke of death as the ‘flight in solitude of the Solitary’. The Protestant reformers, the Puritans and the Jansenists embraced the God-centred view of heaven. Yet alongside this trend, there has been a parallel one which insists on creating heaven in the image of a spruced-up earth. In the second century, Irenaeus of Lyons, taking his lead from Revelation, held that the chosen would, for a thousand years after their death, inhabit what was in effect a renewed earth. In this plan whatever you had been denied the first time round, you received in abundance in the rerun.

Heaven as a compensation for all you have missed on earth has always been an attractive gospel. In Renaissance times, theologians joined with humanists and artists in humanising heaven. Borrowing from the Golden Age and the Isles of the Blest (an alternative form for the Elysian Fields) of classical mythology, they fashioned a ‘forever environment’ where men and women met, played, kissed and caressed against a pastoral backdrop. Often God would be removed from direct participation in this pleasure garden and heaven would be given two or even three tiers, the furthest away being the domain of the exclusively spiritual, characterised solely in terms of intensity of light.

More recently in the eighteenth century, the influential, though much-neglected writings of the Swedish scientist-turned-religious-guru Emanuel Swedenborg gave the earth-linked heaven a romantic edge. He is one of the architects of the modern heaven. His Heaven and Hell, part of a body of works known as Arcana Coelestia, which were much-read and remarked upon by the remarkable William Blake among others, describes the author’s encounter with angels as he moves between the spirit world and the material world. It was an image to inspire both popular nineteenth-century authors and twentieth-century film-makers who turned heaven into a cosy, twee copy of the earth, where love and good will conquer all.

There has always, it should be noted, been traffic between the different positions on heaven. Usually it has ended up in the fudge of the third way. Some of those who once preached of a God-centred heaven changed their mind in later life when it seemed they were about to test the validity of their theories. Augustine, in old age, began describing an afterlife where God was very important but where there was time too for long lunches with old friends and enjoyment of physical beauty, but without, of course, his bête noire, sex.

The rise of Christian fundamentalism has added a new twist to the eternal three-way split. For many born-again Christians have embraced a concept known as rapture, which represents a new departure in thinking about heaven. It has grown out of a very particular reading of St Paul’s prediction that when God descends in judgement ‘those who have died in Christ will be the first to rise and then those of us who are still alive will be taken up in the clouds, together with them, to meet the Lord in the air’ (I Thess 4:14–17). This meeting will, the new breed of fundamentalists believe, be shortlived; a refuge in the time of trial predicted by Revelation before Christ instigates a millennium of direct rule on earth and the visitors to heaven return to take their rightful place at his side. The concept that heaven can be a temporary haven, almost a holiday destination, goes against every other Christian tenet. Yet it is disarmingly popular. A key exponent of rapture, the former Mississippi tug-boat captain turned Christian fundamentalist, Hal Lindsey, has seen his book, The Late Great Planet Earth, sell thirty-five million copies worldwide.

Such a reappraisal illustrates, in one sense, how flexible the idea of heaven (and indeed the New Testament) can be in the hands of believers. Something that can only live in the imagination is, by its very nature, almost impossible to control. Yet for many of us who have some kind of faith, it can be, for much of our lives, almost an irrelevancy. Until very recently, on the rare occasions that I plucked up the courage to look my post-mortem fate straight in the eye, my instinct had always been to postpone thinking about heaven. Focusing on the next world, it seemed to me, was a cop-out.

Heaven, I therefore know from experience, can very easily be left to one side as one of those tricky parts of the total religious package, accepted implicitly but without thought, something to think about on a rainy day. It largely depends on what stage of life you’re at. If the subject did come up in my teenage years at my Catholic school, it was as the flip side of hell, an altogether more worrying entity in those angst-ridden years. Heaven was certainly too much to contemplate in my fallen adolescent state. In my twenties, I lacked the romantic spirit of Keats who, at the age of twenty-five, when passion for life is at its peak (and also just a year before his death), wrote in Ode to a Nightingale:

Darkling I listen; and, for many a time

I have been half in love with easeful Death,

Called him soft names in many a mused rhyme,

To take into the air my quiet breath;

Now more than ever seems it rich to die,

To cease upon the midnight with no pain.

But in my late thirties, the recent experience of losing one of my parents and then a much-loved mother-in-law has led me, if not to welcome death as a form of release like Keats, then to consider both it and heaven as never before. As I drove behind the hearse carrying my mother’s coffin to the church for her funeral, I thought of all the hundreds of times I had seen other sombre processions pass and scarcely paused in the business of living, let alone said a prayer. Belief, A. A. Gill once wrote, is like holding on to the end of a piece of string that disappears into the sky. Sometimes that string is yanked and it forces you to think.

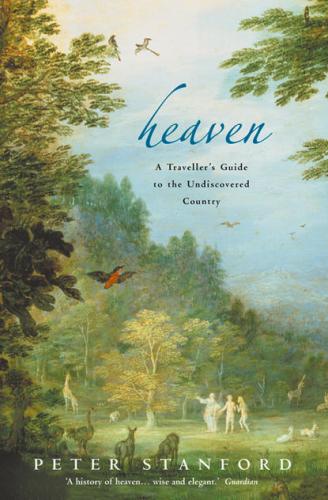

Having had my string pulled, this book is, at least in part, my own traveller’s tale of searching for some sort of answer via a journey, real and imaginative, to the place where the Catholic Church of my upbringing tells me my mother has gone. The notion of a metaphorical or spiritual journey to heaven is a tried, tested and often fruitful one. In both the apocryphal writings of the first centuries AD and in the visionary ecstasies of the medieval age those who told of heaven spoke in terms of having travelled there. Most of the lasting accounts of paradise have effectively been travel books. It is in this spirit that I have included in this account of my own journey brief extracts from the tales told by contemporary travellers who have attempted to go one step beyond, and also, at various key moments in the history of heaven, excerpts from the travel journal I kept when I visited particular places which seemed to offer the possibility of a glimpse of the transcendent.

In the interests of completeness I have tried to keep an open mind and see beyond the more standard tenets of my Christian start in life. Most faiths have some sort of belief in another life but some schedule the route as a domestic departure – i.e. as all about transcending this life. This then remains a book written primarily for a Western audience with a Judeo-Christian heritage, but written in the knowledge that such a heritage cannot be understood or evaluated with looking carefully at the alternatives.

Such a broad scope has the advantage of carrying with it the potential to quell my own greatest anxiety at the start of this journey, namely that there may be nothing at its end, that I may be going nowhere (now or ever), and that heaven is religion’s biggest con-trick, its way of ensuring that churches, synagogues and mosques will remain full and flourishing. If I reach such a conclusion, I comfort myself now, at least I can then fall back on the Buddhist position of seeking enlightenment in this life by way of consolation.

A Gallup Poll in the early 1980s suggested that in the West, at least, the majority of voters still place their trust in heaven, even if its manifesto is no longer very precise. The 71 per cent who signed up for it were only one point down on the number in a similar survey in 1952. As long as there are men and women afraid of death and anxious to believe that it is not the end, there is a ready audience, happy to take the anaesthetic to life’s worries that heaven provides. But perhaps oblivion shouldn’t be an anxiety for any of us. Nothing may be better than the torment which the old-style Catholicism of the Penny Catechism promised in purgatory, limbo or, worst of all, hell. If you put your faith