from Bent’s and the Santa Fe Trail

to the Black Hills

Contents

Copyright

How Did I Get the Idea of Flashman?

Dedication

Explanatory Note

Introduction

The Forty-Niner

Notes

About the Author

The FLASHMAN Papers: In chronological order

The FLASHMAN Papers: In order of publication

Also by George MacDonald Fraser

About the Publisher

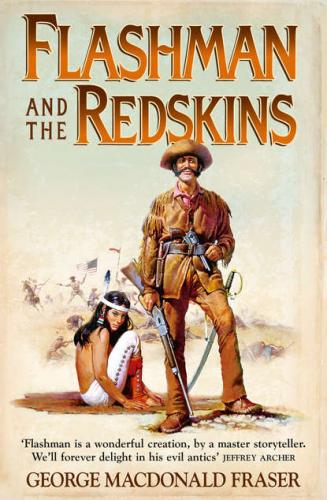

A singular feature of the Flashman Papers, the memoirs of the notorious bully of Tom Brown’s Schooldays, which were discovered in a Leicestershire saleroom in 1966, is that their author wrote them in self-contained instalments, describing his background and setting the scene anew each time. This has been of great assistance to me in editing the Papers entrusted to me by Mr Paget Morrison of Durban, Flashman’s closest legitimate relative; it has meant that as I opened each new packet of manuscript I could expect the contents to be a complete and self-explanatory book, needing only a brief preface and foot-notes. Six volumes have followed this pattern.

The seventh volume has proved to be an exception; it follows chronologically (to the very minute) on to the third packet,fn1 with only the briefest preamble by its aged author. I have therefore felt it necessary to append a résumé of the third packet at the end of this note, so that new readers will understand the events leading up to Flashman’s seventh adventure.

It was obvious from the early Papers that Flashman, in the intervals of his distinguished and scandalous service in the British Army, visited America more than once; this seventh volume is his Western odyssey. I believe it is unique. Others may have taken part in both the ’49 gold rush and the Battle of the Little Bighorn, but they have not left records of these events, nor did they have Flashman’s close, if reluctant, acquaintance with three of the most famous Indian chiefs, as well as with leading American soldiers, frontiersmen, and statesmen of the time, of whom he has left vivid and, it may be, revealing portraits.

As with his previous memoirs, I believe his truthfulness is not in question. As students of those volumes will be aware, his personal character was deplorable, his conduct abandoned, and his talent for mischief apparently inexhaustible; indeed, his one redeeming feature was his unblushing veracity as a memorialist. As I hope the footnotes and appendices will show, I have been at pains to check his statements wherever possible, and I am indebted to librarians, custodians, and many members of the great and kindly American public at Santa Fe, Albuquerque, Minneapolis, Fort Laramie, the Custer battlefield, the Yellowstone and Arkansas rivers, and Bent’s Fort.

G.M.F.

In May, 1848, Flashman was forced to flee England after a card scandal, and sailed for Africa on the Balliol College, a ship owned by his father-in-law, John Morrison of Paisley, and commanded by Captain John Charity Spring, MA, late Fellow of Oriel College. Only too late did Flashman discover that the ship was an illegal slave-trader and her captain, despite his academic antecedents, a homicidal eccentric. After taking aboard a cargo of slaves in Dahomey, the Balliol College crossed the Atlantic, but was captured by the American Navy; Flashman managed to escape in New Orleans, and took temporary refuge in a bawdy-house whose proprietress, a susceptible English matron named Susan Willinck, was captivated by his picaresque charm.

Thereafter Flashman spent several eventful months in the Mississippi valley, frequently in headlong flight. For a time he impersonated (among many other figures) a Royal Navy officer; he was also a reluctant agent of the Underground Railroad which smuggled escaped slaves to Canada, but unfortunately the fugitive entrusted to his care was recognised by a vindictive planter named Omohundro, and Flashman abandoned his charge and beat a hasty retreat over the rail of a steamboat. He next obtained employment as a plantation slave-driver, but lost his position on being found in compromising circumstances with his master’s wife. He subsequently stole a beautiful octoroon slave, Cassy, sold her under