Like Agatha Christie, Carolyn Wells first became smitten with detective fiction after hearing read aloud a book authored by American detective novelist Anna Katharine Green—although for Wells the inspirational text was not Green’s bestselling debut mystery, The Leavenworth Case (1878), but rather a later, then contemporary, Green tale, That Affair Next Door (1897). ‘To a listener entirely unversed in crime stories or detective work it was a revelation,’ Wells recalled. ‘I had always been fond of card games and of puzzles of all sorts, and this book, in plot and workmanship, seemed to me the apotheosis of interesting puzzle reading. The mystery to be solved, the clues to be discovered and utilized in the solution, all these appealed to my brain as a marvellous new sort of entertainment …’

Carolyn Wells’s novice essay in crime fiction was ‘The Maxwell Mystery’, which appeared serially in May 1906, when Wells was 43 years old, and introduced to the world the patrician and perceptive Fleming Stone, by far the most renowned of the author’s series sleuths. Wells published her first full-fledged Fleming Stone detective novel, The Clue, in 1909. A total of 82 Wells detective novels would appear between 1909 and 1942, of which 61 detailed the amazing investigative exploits of Fleming Stone.

During these fecund years, which also saw the publication of Wells’s influential guide to writing mysteries, The Technique of the Mystery Story (1913), Carolyn Wells produced some of the most popular detective fiction in the United States, though admittedly she was far less well-known in the United Kingdom. (However, G. K. Chesterton, creator of Father Brown, once praised Wells as ‘the author of an admirable mystery called Vicky Van’.) In the crime yarns, like Vicky Van, The White Alley and The Curved Blades, which Carolyn Wells published during the 1910s, the decade which immediately preceded the Golden Age of detective fiction, there cohered many of the elements—genteel country house settings, dastardly locked-room murders, fatally ferocious domestic squabbles—that today are commonly associated with mysteries from the bright and blindingly clever era of such insouciant yet implacable master sleuths as Hercule Poirot, Lord Peter Wimsey, Reggie Fortune, Philo Vance and Ellery Queen.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s Carolyn Wells maintained her considerable popularity in the US, with sales of her mysteries more than quadrupling the average sales of most other crime writers. (Among her legion of fans during these years there numbered the young John Dickson Carr.) By early 1937 Fleming Stone detective novels through direct sales had grossed almost one million dollars, something on the order of seventeen million dollars today, putting her in the select company of such Golden Age American mystery writers as S. S. Van Dine and Mary Roberts Rinehart, authors who actually managed to become wealthy though mystery writing. This was a time, we should recall, when most detective fiction devotees borrowed their favoured form of reading fare at the cost of a few cents a day from rental libraries.

Contemporary newspaper interviews with Wells typically took note of her beautiful luxury apartment filled with exquisite antiques. Having been bitten, like her crime-writing countryman S. S. Van Dine, by the collecting bug (though Van Dine’s passion, for a time, was tropical fish), Wells amassed a valuable hoard of nearly five hundred Walt Whitman volumes, which she bequeathed upon her death to the Library of Congress. In her pursuit of Whitman she was amply assisted by renowned bookseller Alfred F. Goldsmith, who for three decades, up to his death in 1947, did business from the Sign of the Sparrow, his basement bookshop on Lexington Avenue in Manhattan, a veritable Mecca for bibliophiles. Together in 1922 Wells and Goldsmith authored A Concise Bibliography of the Works of Walt Whitman.

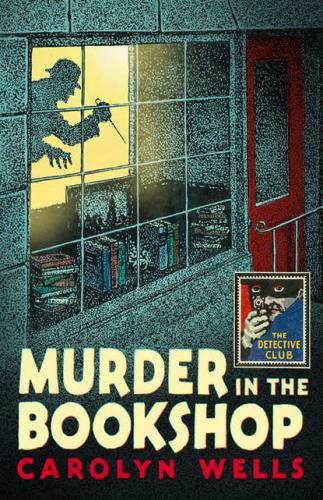

Fourteen years after her collaboration with Alfred F. Goldsmith, Carolyn Wells fictionalized the Sign of the Sparrow as the site of the first slaying in her 43rd Fleming Stone detective novel, the bibliomystery Murder in the Bookshop (1936), which she also dedicated to her friend. Alfred Goldsmith has been credited with the droll remark that ‘the book business is a very pleasant way of making very little money’, yet in Murder in the Bookshop a rare book really is something to die for, with characters desperately vying for possession of a tome worth an estimated $100,000 (about $1.7 million today). The fatally contested book, an abstruse treatise on taxation, has been thrice signed and annotated by no less a personage than Button Gwinnett, one of the 56 signers of the American Declaration of Independence, whose autograph remains in especially high demand from collectors today on account of its rarity. Gwinnett was slain in a duel less than a year after he signed the Declaration and today there are only ten of his autographs held in private hands, one of which recently sold in New York for $722,500.

When avid book collector and Button Gwinnett fancier Philip Balfour is found literally skewered to death in John Sewell’s rare bookshop, there are suspects aplenty in the wealthy New Yorker’s death, including not only John Sewell and his smooth assistant, Preston Gill, but Balfour’s charming young wife, Alli; his earnest librarian, Keith Ramsay (who has admitted to being enamoured with Alli); and his own son by a prior marriage, Guy Balfour, something of a feckless man-about-town. Though the police find themselves baffled by the murder of Balfour and the theft from Sewell’s shop of the Button Gwinnett book, Fleming Stone fortunately is at hand to provide illumination. Yet even the great Fleming Stone has his hands full with crime this time, what with a second devilish murder (this one taking place in a locked bathroom), a ruthless abduction and the Great Detective’s own entrapment inside a locked room! In this deadly game of Button, button, who’s got the button?, will it be Fleming Stone or the murdering fiend who comes out the winner? You surely do not have to be another Fleming Stone or Philo Vance to deduce the answer to that question.

Appended in this volume to Carolyn Wells’s Murder in the Bookshop is ‘The Shakespeare Title-Page Mystery’, a short story originally published in 1940 in The Dolphin, the journal of the Limited Editions Club of New York. Eleven years earlier Wells had provided an introduction for the Club’s lovely edition of Walt Whitman’s literary landmark, Leaves of Grass, and it was to The Dolphin in 1940 that she contributed one of her very few works of short detective fiction. This tale of literary shenanigans (with murder included) concerns the sudden appearance of a pair of putative first edition copies of Shakespeare’s narrative poem Venus and Adonis (1593), likely the Bard’s very first publication. Possibly Wells was partly influenced in the writing of this mystery by recent shocking revelations concerning the nefarious activities of British bibliophile Thomas J. Wise, who in fictionalized form figures in British mystery writer E. R. Punshon’s detective novel Comes a Stranger (1938).

At the end of Carolyn Wells’s story—one of the last pieces of detective fiction which the author, who died in 1942, ever published—we learn of a rare book that providentially survived German air raids in London and made its way over to safety in the United States. Until the war is over and the book’s true owner is located, pronounces one of the characters in the story, good care must be taken of it: ‘The precious little volume is also a refugee, and a refugee is ever a sacred trust.’ Wells did not herself survive the war, passing away in her eightieth year, and her books shortly afterward went out of print for many decades, but today vintage mystery fans can in one volume read both ‘The Shakespeare Title-Page Mystery’ and Murder in the Bookshop, a pair of bibliomysteries that are among the rarest works in Wells’s vast—and once vastly popular—corpus of crime fiction.

CURTIS EVANS

February 2018

MR PHILIP BALFOUR was a good man. Also, he was good-looking, good-humoured