‘That’s because you never had an imaginary friend,’ laughed Ellie. ‘I did, till I was ten. Only children often do.’

‘Adults too,’ agreed Dalziel. ‘The Chief Constable’s got several. I’m one of them. What’s the story about anyway?’

‘About a little girl who gets kidnapped by a nix – that’s a kind of water goblin.’

A breeze sprang up from somewhere, hardly strong enough to stir the petals on the roses, but sufficient to run a chilly finger over sun-warmed skin.

‘Could have had that drink,’ said Dalziel accusingly to Pascoe. ‘Too late now. Come on, lad. We’ve wasted enough time.’

He thrust the book into Ellie’s hands and set off through the house.

Pascoe looked down at his wife. She got the impression he was seeking the right words to say something important. But what finally emerged was only, ‘See you then. Expect me … whenever.’

‘I always do,’ she said. ‘Take care.’

He turned away, paused uncertainly as if in a strange house, then went through the patio door.

She looked after him, troubled. She knew something was wrong and she knew where it had started. The end of last year. A case which had turned personal in a devastating way and which had only just finished progressing through the courts. But when if ever it would finish progressing through her husband’s psyche, she did not know. Nor how deeply she ought to probe.

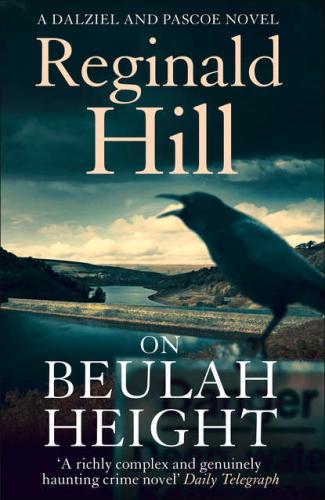

She heard the front door close. She was still holding Rosie’s book. She looked down at the cover illustration, then placed the slim volume face down on the floor beside her and switched the radio back on.

The strong young voice of Elizabeth Wulfstan was singing again.

‘Look on us now for soon we must go from you.

These eyes that open brightly every morning

In nights to come as stars will shine upon you.’

Pascoe sat in the passenger seat of the car with the window wound fully down. The air hit his face like a bomb blast, giving him an excuse to close his eyes while the noise inhibited conversation.

That had been a strange moment back there, when his feet refused to move him through the doorway and his tongue tried to form the words, ‘I shan’t go.’

But its strangeness was short-lived. Now he knew it had been a defining moment, such as comes when a man stops pretending his chest pains are dyspepsia.

If he’d opted not to go then, he doubted if he would ever have gone again.

He’d known this when Dalziel rang him. He’d known it every morning when he got up and went on duty for the past many weeks.

He was like a priest who’d lost his faith. His sense of responsibility still made him take the services and administer the sacraments, but it was mere automatism maintained in the hope that the loss was temporary.

After all, even though it was faith not good works that got you into the Kingdom, lack of the former was no excuse for giving up the latter, was it?

He smiled to himself. He could still smile. The blacker the comedy, the bigger the laugh, eh? And he had found himself involved in the classic detective black comedy when the impartial investigator of a crime discovers it is his own family, his own history, he is investigating, and ends up arresting himself. Or at least something in himself is arrested. Or rather …

No. Metaphors, analogies, parallels, were all ultimately evasive.

The truth was that what he had discovered about his family’s past, and present, had filled him with a rage which at first he had scarcely acknowledged to himself. After all, what had rage to do with the liberal, laid-back, logical, caring and controlled Pascoe everyone knew and loved? But it had grown and grown, a poison tree with its roots spreading through every acre of his being, till eventually controlling it and concealing it took up so much of his moral energy, he had no strength for anything else.

He was back with metaphors, and mixing them this time, too.

Simply, then, he had come close from time to time to physical violence, to hitting people, and not just the lippy low-life his job brought him in contact with who would test a saint’s patience, but those close around him – not, thank God, his wife and his daughter – but certainly this gross grotesquerie, this tun of lard, sitting next to him.

‘You turned Trappist or are you just sulking?’ the tun bellowed.

Carefully Pascoe wound up the window.

‘Just waiting for you to fill me in, sir,’ he said.

‘Thought I’d done that,’ said Dalziel.

‘No, sir. You rang and said that a child had gone missing in Danby and as that meant you’d be driving out of town past my house, you’d pick me up in twenty minutes.’

‘Well, there’s nowt else. Lorraine Dacre, aged seven, went out for a walk with her dog before her parents got up. Dog’s back but she isn’t.’

Pascoe pondered this as they crossed the bypass and its caterpillar of traffic crawling eastwards to the sea, then said mildly, ‘Not a lot to go at then.’

‘You mean, not enough to cock up your cocktails on the patio? Or mebbe you were planning to pop round to Dry-dock’s for a dip in his pool.’

‘Not much point,’ said Pascoe. ‘We’ll be passing the Chateau Purlingstone shortly and if you peer over his security fence, you’ll observe that he’s practising what he preaches. The pool is empty. Which is why they’ve taken the girls to the seaside today. We were asked to join them, but I didn’t fancy wall-to-wall traffic. A mistake, I now realize.’

‘Don’t think I wouldn’t have airlifted you out,’ growled Dalziel.

‘I believe you. But why? OK, a missing child’s always serious, but this is still watching-brief time. Chances are she’s slipped and crocked her ankle up the dale somewhere, or, worse, banged her head. So the local station organizes a search and keeps us posted. Nothing turns up, then we get involved on the ground.’

‘Aye, normally you’re right. But this time the ground’s Danby.’

‘Meaning?’

‘Danbydale’s next valley over from Dendale.’

He paused significantly.

Pascoe dredged his mind for a connection and, because they’d just been talking about Dry-dock Purlingstone, came up with water.

‘Dendale Reservoir,’ he said. ‘That was going to solve all our water problems to the millennium. There was an Enquiry, wasn’t there? Environmentalists versus the public weal. I wasn’t around myself but we’ve got a book about it, or rather Ellie has. She’s into local history and environmental issues. The Drowning of Dendale, that’s it. More a coffee-table job than a sociological analysis, I recall … Sorry sir. Am I missing the point?’

‘You’re warm, but not very,’ growled the Fat Man, who’d been showing increasing signs of impatience. ‘That summer, just afore they flooded Dendale, three little lasses went missing there. We never found their bodies and we never got a result. I know you weren’t around, but you must have heard summat of it.’

Meaning, my failures are more famous than other people’s triumphs, thought Pascoe.

‘I think I heard something,’ he said diplomatically. ‘But I can’t remember much.’

‘I remember,’ said the Fat Man. ‘And the parents, I bet they remember. One of the girls was called Wulfstan.