By the time war was actually declared in September 1939, all three of the women’s services had been deluged with applicants, and tens of thousands of young women were soon donning their distinctive new uniforms – khaki for the ATS, Air Force blue for the WAAF, and navy for the WRNS. When conscription for women was introduced in the National Service Act of 1941, the ranks of the services were swelled further, as many girls chose the rigours of military life over hazardous work in a munitions factory or the hard labour of tilling the fields with the Land Army. There were some who refused to be drafted – 257 female conscientious objectors found themselves imprisoned as a result of their principles – but most girls reported for duty reasonably willingly and did their best to fit into life in the forces, however alien the military environment might seem to them.

In many ways, the girls in uniform were aspirational figures, and during the war their image was appropriated by advertisers keen to appeal to young, independent-minded women. But they were far from universally popular. Old sweats in the military were often mistrustful of their new colleagues, and anxious about sharing facilities with them. One veteran RAF officer told the BBC of his horror at the thought of ‘petticoats’ on his air base, and General Eisenhower himself was initially opposed to working alongside women, although the competence and professionalism he saw at his HQ in London were enough to make him change his mind.

Some men, whether military or civilian, feared that girls in uniform were getting ideas above their station. ‘The menace,’ fumed one magazine editor, ‘is the woman who thinks she ought to be flying a high-speed bomber when she really has not the intelligence to scrub the floor of a hospital properly, or who wants to nose around as an air-raid warden and yet can’t cook her husband’s dinner.’ Others complained that servicewomen were encroaching into previously male-dominated spaces – most shocking of all, they were seen accepting drinks from strangers in pubs.

The government attempted to calm the male population with a pamphlet that asserted reassuringly, ‘The girls look healthy and happy, and clearly most of them will make better wives and mothers and citizens, if only because they have had some physical and mental training.’ But many British people – men and women alike – were unconvinced. The confidence that many girls exuded when they put on a military uniform was seen by some as unladylike, and they were frequently accused of having loose morals – in fact many civilians fervently believed that women in the forces were little more than prostitutes. In popular slang, the letters ATS were said to stand for a number of lewd expressions, from ‘Any time, Sergeant!’ to ‘American Tail Supply’. Army girls were referred to colloquially as ‘officers’ groundsheets’, while WAAFs were labelled ‘pilots’ cockpits’ and the girls in the Navy were the butt of a popular expression – ‘Up with the lark and to bed with a Wren.’

The tabloid press didn’t help matters. ‘TOO MANY MISFITS IN THE ATS AND WAAF,’ thundered the Express, while the Daily Mail ran a poll on what their readers hated most about the war, in which ‘women in uniform’ came top.

Such was the strength of feeling among the public that Parliament set up a committee to look into the alleged moral failings of the women’s forces. In August 1942 the social reformer Violet Markham reported confidently that the accusations levelled against the girls were groundless. Although some servicewomen had been discharged for illegitimate pregnancies – in the ATS this was known as ‘going para 11’, after the section of the rulebook that dealt with such cases – the illegitimate birth rate in the services was in fact lower than among the civilian population at the time, and the rate of venereal disease among servicewomen was half that among men.

It seems particularly unfair that so many civilians looked down on the girls in uniform, since the part they played in winning the war was a crucial one. Without the contribution made by the WAAF, for example, the Royal Air Force would have needed an extra 150,000 men – a figure all but impossible to muster. And although the girls of the three forces were forbidden by Royal Proclamation from personally firing deadly weapons, they were closely involved in many of the key events of the war, and frequently found themselves in harm’s way. In 1940, ATS ambulance drivers serving with the British Expeditionary Force in France were caught up in the frantic rush to evacuate at Dunkirk. Four years later, WAAF medical orderlies were among the first women to return to Europe after D-Day – when their air ambulances landed in Normandy just a week after the invasion, they were hailed as ‘Angels of Mercy’.

Many servicewomen won medals for their bravery in terrifying circumstances – among them Daphne Pearson, who dragged a pilot out of his crashed plane just before a bomb exploded, hurling herself on top of him to shield his body from the blast. Others made critical contributions to Allied operations, such as Constance Babbington Smith, the first person to locate the launch sites of Hitler’s deadly V1 flying bombs. Girls from all three forces worked under top-secret conditions at Bletchley Park, helping to shorten the war by at least two years – Churchill later referred to them as ‘the geese that laid the golden eggs but never clucked’.

Then there were the courageous young women who shed their military uniforms when they were transferred to the Special Operations Executive, a spy network whose operatives were trained to kill with guns and explosives, and whose life expectancy in occupied Europe could be measured in weeks. Among them was former WAAF Noor Inayat Khan, who, after her comrades in the field were arrested, found herself the only link between a resistance network in Paris and the Allied command in London. In time she too was captured and taken to Dachau concentration camp, where she was executed with a bullet to the head.

Throughout the course of the war, around two thousand WAAFs, Wrens and ATS girls lost their lives in the service of their country. Some died on their bases around Britain, the victims of enemy bombing raids. Some were buried in foreign fields far away from home – in Cairo, Kuala Lumpur or Tel Aviv. Others were lost at sea, among them the 23 Wrens who drowned when the SS Aguila was sunk in the first U-boat attack on an Allied shipping convoy.

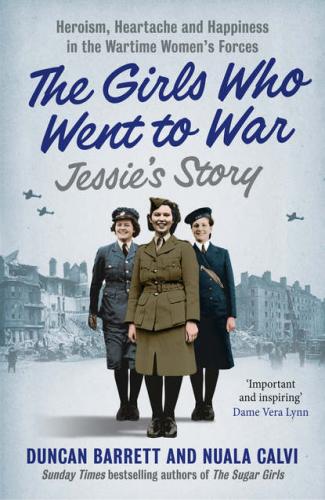

Overall, more than half a million women served in the armed forces during the Second World War. This eBook tells the story of just one of them. But in her story is reflected the lives of hundreds of thousands of others like her – ordinary girls who went to war, wearing their uniforms with pride.

The morning of Sunday 3 September 1939 was a sunny one, and Jessie Ward was out digging potatoes in the garden of her family’s house in the little village of Holbeach Bank, Lincolnshire. A petite girl with big blue eyes and dark hair, she looked far younger than her 17 years, but despite her slight build her mother always made sure to keep her busy with chores. That particular day Mrs Ward was looking after a sick friend’s little girl, so Jessie had even more to do than usual.

Just after 11 o’clock that morning, Mr Ward called his wife and daughter into the living-room, where they found him listening intently to the bulky wooden wireless set. There was a crackle, and then the clipped tones of Neville Chamberlain rang out of the machine. ‘This morning,’ he announced, ‘the British Ambassador in Berlin handed the German Government a final note, stating that, unless we heard from them by 11 o’clock that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would exist between us.’

Jessie saw her mother and father exchange an anxious glance.

‘I have to tell you now,’ the Prime Minister continued, ‘that no such undertaking has been received, and that consequently this country is at war with Germany.’

Mr Ward leaned forward, holding his head in his hands. ‘It can’t happen again,’ he muttered. ‘It just can’t.’ Jessie knew that her father had spent much of the last war watching his fellow soldiers in the Royal Warwicks being gassed and slaughtered in front of him, and had witnessed his best friend being shot in the head.

‘Well, we’ll probably be invaded, being so close to the coast,’ said his tiny wife, matter-of-factly. ‘I’d better take Tina back to her mother. Jessie, you’ll have to do the Sunday dinner.’

‘Yes,