“Who are you talking about? Never mind. Whoever he is, keep him. I don’t want him,” Jordan assured him.

Blood suffused the bishop’s face. “You lie—”

Without warning he knelt over her and caught a hand under her midsection. His other hand worked behind her. The point of the syringe poked, then found its way into her rectum. She heard the squeak of metal and a squishing sound as he awkwardly tried to work the brass and tin piston with the use of only one hand and arm.

She tried to wriggle free of the discomfort, knowing that in seconds she would feel the cold chill of water flushing her bowels into the waiting bucket.

The voice at the curtain rose. “I bring a message for the bishop,” it announced. “Regarding the matter we discussed earlier. I come to inform him that his companion has just departed in a group of others.”

The clyster left her and hit the floor with a clatter. The bishop hurried off, forgetting her and his crazy threats. With a twitch of the curtain, he stepped outside it to speak with the interloper. There was a brief conversation to which Salerno and the others listened unabashedly.

This was her chance.

Jordan stumbled upright and managed to stuff her bare feet into her sturdy buckled man’s shoes, which had been set by the door. Salerno’s cloak, lying across the chair back, brushed her arm. She snatched it up to cover her nakedness. All this seemed to occur in slow motion, but when she glanced behind her, no one had moved and she knew only seconds had passed.

Carefully, Jordan opened the back door the disgruntled Englishman had so recently used to exit the theater. The streets here were dangerous. But remaining in the theater posed a danger as well.

Behind her, someone shouted, noticing she was poised for flight. She plunged from the room into the nearly deserted street outside, making a run for it. The door banged behind her, echoing across the piazza. She heard it open again, and then came the sound of pursuit.

The tattoo of her own clunking footsteps on the rain-washed pavement drowned out any further sounds. Any minute she expected Salerno’s hands to grab her. Her breath was strangled with the fear of imminent capture.

But it never came. The cloddish shoes were practical and carried her swiftly away from the theater, along winding brick streets. The root had dulled her reflexes and confused her mind, but the sweet smell of rain-scented air was quickly dispelling its effect.

Footsteps sounded behind her. She turned into an alley, ducked into a crevice between two buildings, and waited. The steps faltered. Nearby, she heard Salerno’s voice.

“I’m searching for a young—person—wearing a crimson cloak,” he told someone. “And possibly the bauta as well.”

She couldn’t decipher the mumbled response he was given but knew it had displeased him when his sharp curse cut the air. This was quickly followed by the sound of his footsteps veering away.

When they grew faint, Jordan slipped from the alley and ran in the direction opposite from that which he’d gone. The streets twisted and angled, but she knew her way home from here. First, she had to get over the Rialto. Once beyond the bridge, home was only thirty or so turns away by street.

Then it occurred to her that home was out of the question. Salerno would look for her there immediately, claiming she owed him more hours of her time.

Could she find harbor with one of her male friends tonight? Paulo and Gani could always be counted on to join in any escapade. But if she turned up at either of their homes wearing only a cloak, they would whisk it from her, teasing. And when they discovered her true sex—when they discovered the deceit she’d perpetrated for all the years that she’d known them as friends—she feared what their reactions might be.

She scurried onward, unable to think of anything except the need to reach the bridge, which served as the only link across the Grand Canal that divided Venice. In the distance ahead, she saw its stone arch. The smell of the sea stung her nose as she rushed toward it.

She saw no one behind her. Heard no one. But still her heart thumped in time with her steps. Her breath was tortured, her entire body tense with fear of discovery. Would Salerno jump out at her from a cross street or one of the alleys, preventing her from reaching the bridge and any chance of escape?

Only a single gondola bobbed along the quay ahead, clacking softly. She had no money for its hire. Where would she go even if she could pay?

Lanterns along the bridge flickered, casting diamonds across the murky waters of the canal. The rain had stopped, and the night was turning foggy. The Palazzos Manin and Bembo along the Riva del Ferro, where shipments of iron were unloaded by day, were barely visible across the canal. An inky blackness of sky and sea loomed like a gaping maw waiting to swallow her.

Above her, on the balconies of the houses along the Riva del Vin, courtesans with bosoms far more ample than hers discreetly offered the use of their bodies to passersby in spite of the weather. If she called to them would they take pity on her? Unlikely, unless she had coin to offer.

Most of the vendors in the shops that stood atop the Rialto had gone home for the day by now. Cries from those who dwelled in squalor under the bridge came on the wind, frightening her.

If she’d been pronounced a girl nineteen years ago, she and her mother might be there among them. They would only have received a small dowry that wouldn’t have lasted long in view of her mother’s capricious spending.

Whores and beggars were rife in Venice since the French had sacked the city under Napoleon. By now the two of them would be huddled under the bridges like the rest of Venice’s poor. Though she might have somehow managed to find a way to survive, her mother would have withered under the strain and degradation.

Ahead, the bridge-dwellers stirred, calling to a well-dressed gentleman. “Signore! Signore! Look my way.”

She heard a noise behind her. Salerno? Turning back to look, she lunged forward…

And crashed into a human wall.

6

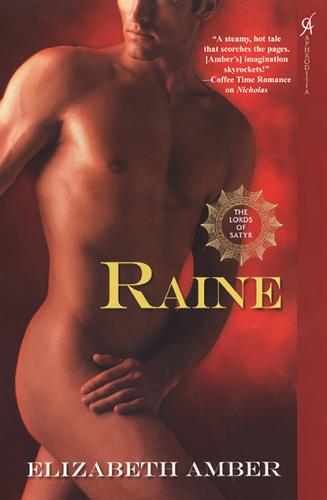

The golden hammer chimed eight times in the Campanile di San Marco as Raine strode down the steps of the lecture hall. He was surrounded by a half-dozen vintners who still discussed the lecture on phylloxera, which they’d all attended.

“What do you think of the French government’s increasing their 30,000 franc prize to 300,000 for anyone who can produce a cure for the phylloxera?” someone asked.

“Idiotic,” said Raine.

“I agree,” said one of the others. “The recitation of suggestions for a curative we were subjected to was a waste of four hours if you ask me. That blasted bug will go on its merry way sucking the sap and life from our vines with no hindrance from the French from the sounds of things.”

Someone else spoke up. “Still, I think the French should be the ones to pay for a cure, if anyone does. They’re the most desperate, since their grapes succumbed to the pest first.”

“It’s not the right way to go about things,” Raine insisted. “You all heard what stupid notions the offer of a reward has put rise to.”

One of his companions laughed. “And the ones the French official read aloud to us were supposedly thought to be the most viable of the lot. Considering that, I shudder to imagine what the rejects must have been!”

Just then, the bishop came running up behind the group, out of breath, causing a brief cessation of conversation. Catching Raine’s eyes on him, he blushed like a schoolgirl.

Raine had forgotten him until now. Surprisingly, the loquacious bishop hadn’t made his presence or his opinions known in the lecture hall.

“I believe my favorite was the suggestion that live toads should be buried beneath each grapevine to leech the phylloxera from the