My face began to boil with irritation.

“Here’s my proposal,” I commanded. “I will paint the picture. You don’t have to pay me unless you have some kind of deadline, and then we can work out a fair price.”

Silence. Phone-line-dead silence.

“Mother?” I shook the phone to jiggle the battery.

“Yes, Emily. I don’t know about this. I feel it’s sort of like using floral arrangements made with flowers from your garden.”

“Huh?”

“Oh, darling, do I need to pontificate this awkward fact to you? What’s the point of having a painting done by a member of the family—not showing the expense we put into it?”

I could hear her tap-tap-tap to the counter with her expertly painted nail.

“I believe it’s done all the time. Even by your distinguished John Singer Sargent. Perhaps it has something to do with family believing in the gifts of their family. Preferring to patronize them over some random stranger.”

“Oh, all right,” she relented. “And of course I will pay you.”

Relieved. I did like the idea of being paid for my work, as I had not been entirely comfortable with the concept of having Henry give me an allowance. Perhaps I wasn’t entirely uncomfortable in having an allowance. I mean, I do need to maintain my looking pretty for him, the purchasing of pretty things for our home that we will both appreciate.

“Also, I do get a bit worried about your business sensibilities. Perhaps you should consider getting one of those business managers?” she said.

“But I have one. A very good and high-end one I found on Fifty-seventh Street,” I said, looking at my Smythson business planner, impressed with myself in not having to lie.

“Very well then. I expect to see a sketch two weeks from today. That’s April second, love.”

And with the frightening realization that I was under the Queen Mother’s employment, she hung up the phone. Oh, for God’s sake, the woman would always find a way to have a hold on me.

I opened up my satchel, leaned against the kitchen table, and pulled out my sketchbook. Furiously drawing images that had no hope, based on the fury of a windstorm pushing ideas along the slippery coils in my brain.

Henry walked into the kitchen, rubbing one of his eyes with his knuckle like a little boy in drop-seat footsie pajamas with a blankie. A shadow crept over my face as he loomed over me, locking me into my seated position with his arms and peering over my pad.

“Whatcha doing there, Emily? Drawing two figures who are about to duel? Or is it fencing?”

He was right. The figurines were embroiled in some sort of face-off, about to have it out. Perhaps their combative poses were made because Henry was still in the doghouse.

“Just working on a commission.”

“Really,” he mused. “And this is all before 9:00 AM,” he added, looking to the microwave clock that flashed 8:44 AM. “I must say that I’m impressed.”

I tore off a sheet and added it to my pile of rejects with an attempt at another sketch, but became annoyed with the mess I kept adding to. Neatly stacking up the scraps of my work, I gathered the papers and walked over to the trash, which was burping up garbage. Lining the top of the bin with the heavy vellum paper, I pushed down the garbage like a compressor.

Feeling Henry’s gaze, I turned to him, only to be under the scrutiny of his bemused smirk, which was exhilarating in a sexual context but now just added to my annoyance.

“You know, Em. A new place will be ideal for your painting. This realtor at the Gallagher Group described to me this promising loft on Grand Street. ‘Stunning! Duplex! Balcony! Sun-flooded!’” he exploded. “Sounds ideal. And enough room for a studio so you can paint properly. With a real disposal system,” he laughed, right as my head was about to free-fall into our garbage.

I stood up, wiping a strand of hair behind my ear. The idea of a “sun-flooded” loft did have considerable appeal. I pictured myself with an eight-foot canvas and little brush stemming from my hand like a wand. Wearing black capris and ballet shoes in that Lee Krasner fifties artist chic sort of style. Always picturing my outfits with the setting.

Henry seated himself at the table, lifting up the box of cereal to give Tony’s mug a closer inspection. I situated a bowl and spoon on his place mat, vaguely registering how our habits resembled that of an old married couple with battery-operated ears.

“Frosted Flakes?”

Henry preferred the kind of bird-feed cereal you found at a store where the tattoo-fingered cashiers have medical degrees, assuming he’d start his day off sensibly, when really the nutrition facts were almost identical to Frosted Flakes unless you had a need for fiber, low sugar, and iron (something I’ve already researched). Essentially, you needed about ten bowls of either cereal to get all of the vitamins and nutrients you need, and Henry wasn’t that hungry in the morning, but I could eat ten bowls of cereal any time of the day (something I’ve been known to do). We also rarely shopped at grocery stores, preferring the charm and unprocessed foods of specialty markets.

“Since when did we start eating Frosted Flakes, Em?”

“I must have made a mistake at the store,” I said without meeting his eye. Not that I was ashamed of my sugary eating habit, I just couldn’t have him think that I’ve fallen for commercial marketing.

Pouring his bowl, Henry discovered the damn IQ test on the back of the box. The wrinkle of his brow and affected looks of pondering into the air indicated that he had found something redeemable in the kid-brand food.

Repositioning the box so he could read the answers on the side panel, I paid particular attention while he tallied up his answers. Henry then applauded to himself while reading the box.

“This stuff is a joke!”

Oh, please.

“Now how can we expect to further advance the intelligence of this country’s youth and, to use Kellogg’s words, ‘Jump-Start Your Brain’ when this is about as simple and useless as a game of tic-tac-toe!”

Good thing I didn’t circle my answers on the box.

“Tic-tac-toe!” he echoed.

“Yes, tic-tac-toe. Speaking of which, the painting I’m working on is for my mother.”

I broke Henry’s interest from that demoralizing cereal box.

“Your mother?”

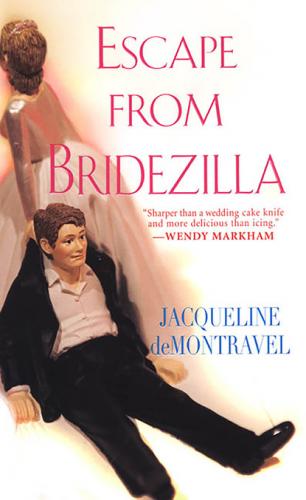

“Yes. Quite amusing, really. You see, she wants me to paint a portrait. Of us! A wedding portrait to maintain some family tradition that keeps the divorce rate down because it would depreciate the value of some expensively commissioned pieces.”

“You and me? A wedding portrait? Commissioned by your mother?”

For a boy who just scored in the leading percentile of our nation’s population, he appeared to be a bit of an imbecile.

“I promise not to inconvenience you in any way—your time—and we only have to hang the picture whenever my mom comes to visit. Which I promise will be infrequently.”

Infrequently for certain, otherwise Henry and I will break a long-standing family tradition where I’ll be the first (but not necessarily the first deserved) Briggs member to have a divorce.

“No. Of course I don’t see this as an inconvenience. It’s just so incredibly Edith Wharton of your mother to come up with such an idea.”

Henry laughed, spooning some soggy flakes into his mouth that, I acutely observed, seemed to be giving him energy despite the fact that they weren’t as smart as his regular flakes. They’re all just flakes, I again assumed.

Henry