Robbie and Tim walked towards the booth area with the drinks. Robbie handed Chris his beer and they both skulled in unison. Lemon’s eyes widened in anger and Tim was amazed to discover he’d accidentally drunk her bourbon. He handed her the water.

‘What am I supposed to do with that?’ she demanded.

‘Throw it on the fire?’ suggested Tim, then before she could explode with her usual fury, he collared Robbie.

‘I don’t suppose you blokes could give us a lift?’

Chris would’ve refused but it was Robbie’s car and what sort of arsehole leaves people to burn in a bushfire?

‘For fuck’s sake!’ swore Chris, as Robbie gave his assent to the couple. Then, grudgingly accepting his humane duty, Chris said: ‘Right … let’s get out of here.’

Wednesday: Ten Days Before the First Wave

Chapter 5

An Evil Child

Conan was falling.

More correctly, he was about to fall from a tall building, having ridden an elevator until it opened onto a long drop in a cityscape he knew only in his dreams. The floor of the elevator seemed to crumble under his feet, then moments later he was awake, with a jolt of adrenalin catching his breath and the dream city fading as he realised his phone was ringing.

He winced with guilt when he saw the number displayed.

‘Hi, Ma.’

‘Conan?’

He’d promised about a week ago to go over and help her with something or other, but as usual he’d been distracted.

‘Where are you?’

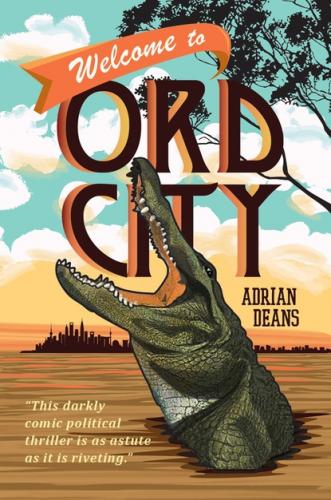

‘Ord City … it’s a work thing.’

‘Ord City, WA? I was there yesterday … or last week.’

‘It’s not a virtual job, Ma … I’m really here.’

‘I don’t see the point of going anywhere for real these days,’ she lectured. ‘Virtual travel is just as good … better, because you get to sleep in your own bed.’

Conan’s mother lived in a retirement village in one of the many vast estates that had sprung up on the fringes of all major cities in the last twenty years. Conan tended to visit about once a week. Or at least once a fortnight, but it must have been close to a month since he’d seen her – not that she’d notice.

‘I lost another boyfriend last night … they can’t keep up with me.’

Her boyfriends tended to die in real life because they got overexcited in Virtual Youth – one of the many virtual sex sites but specially catering for the elderly.

‘What keeps you goin’, Ma?’

‘I don’t really care about them, so I don’t get too excited.’

‘That’s really profound.’

‘It’s good advice, Conan … you should try it next time you get married.’

Conan stared at the ceiling fan and refused to take the bait. His mother liked nothing more than to lecture him about his appalling love life while boasting about her many virtual conquests.

‘Conan … I need money.’

‘You’ve got plenty of money.’

‘Super doesn’t pay for Virtual Youth … I have to dip into my capital. That arsehole Keating should have made us pay 20% … or even 30% into super, then maybe I’d have a decent retirement.’

‘Well, do without Virtual Youth. If you don’t waste capital your super will keep you in pretty good shape for the rest of your life … your real life. ‘

‘You don’t understand … I don’t like real life any more. Virtual Youth is so much better, but I can only afford it for another six months … unless you help me.’

‘Why don’t you just start caring?’

‘… I beg your pardon?’

‘Why don’t you start caring about your virtual partners? Then you might get overexcited and … erm … and won’t need Virtual Youth anymore.’

‘You’re evil, Conan. I don’t believe I could have raised such an evil child.’

But she was laughing.

‘We’ll talk about it when I get back, Ma … okay?’

‘Okay, Conan. You be careful in Ord City … it’s full of weirdos.’

‘It is?’

‘Trust me. I’ve been there.’

• • •

Just after nine o’clock, Conan met Loongy outside a ramshackle building in Dutton Close, surrounded by bamboo scaffolding and half the windows blackened from a recent fire. Despite its dilapidated condition, the building was teeming with life – hordes of grimy, happy children mucked about in the street which was also full of dogs, cats, vendors peddling cheap clothing, weird looking fruit and vegetables and makeshift snacks while dozens of motorbikes threaded through semi-abandoned road works and stagnant puddles. The street smelled of exhaust fumes, dead water and frying onions, and somehow reminded Conan of a medieval town he’d explored on Virtual History Channel.

A number of the children suddenly accosted Conan, thrusting battered-looking wares for sale at him, and Loongy snapped at them in Chinese, sending them scampering.

Conan forced himself to remain impassive but Loongy knew what he was thinking.

‘Just because I’m sixth generation doesn’t mean I can’t speak Cantonese.’

‘Of course not,’ agreed Conan, following him into the building, still uncertain whether Loongy was weirdly paranoid or brilliantly pulling his leg.

The foyer was a shambles of piled up garbage bags, a scatter of small vials and discarded building materials. The elevator shafts were two gaping black holes and obviously not working.

‘It’s on the fifth floor,’ said Loongy, entering a dim stairwell that was lit from several floors up and stank of urine. ‘I bet you’re wondering: how do people live in this?’

‘Not really,’ lied Conan, trying not to breathe with all the piss stink.

‘This is what they’re used to in Asia,’ explained Loongy. ‘This is what they bring with them … this, and Habal Tong.’

‘You’re not a fan?’

‘You come to Australia, you assimilate!’ insisted Loongy, raising his voice. ‘You don’t like our ways … fuck off back to Asia! Fuck off!’

Conan kept waiting for Loongy to grin, to acknowledge he’d been joking, but Loongy was muttering fiercely to himself, seeming more Chinese every second.

On the fifth floor, they left the stairwell and passed along a corridor with damp carpet that stank of mould. A dog barked from a darkened doorway and faces, old and young, mainly Chinese but at least one family of Indians, or Sri Lankans, peered at them as they strode past until they turned a corner and found two uniformed officers sitting outside a door taped across with blue and white checks.

The two officers leapt to their feet, one of whom was Agent Ping who’d been reading an old paper-style book, which he half hid behind his back.

‘Chairs,’ remarked Loongy, irritably. ‘Where you get chairs?’

‘Neighbours,’ said Ping. ‘They’ve been very helpful.’

‘They better not be from inside,’ said Loongy, producing