Your favourite, Lady Demeter, Cassandra, captive of Agamemnon, shall live or die as fate wills. Cut the strings of these minor puppets, children, make peace with each other. There is a greater matter to be considered. Your intervention has woven their threads into a tapestry in which all the Gods are interested.'

'Lord?' asked Athena of the glittering helmet. 'What matters?'

'The House of Atreus,' the great voice intoned.

The golden apple fell to the marble floor unheeded.

I

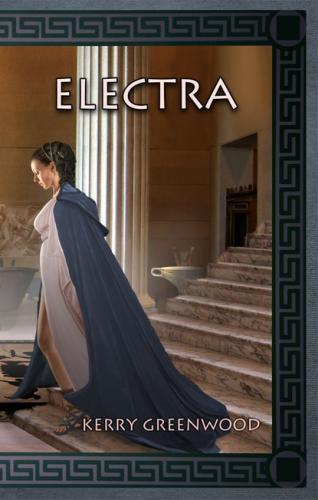

Electra

I knew she was going to kill him when she laid out the sacred tapestries.

I stood at the head of the marble stairs and watched them unroll across the floor, blurred by the feet of the children of Atreus. Intricately embroidered, many-figured with holy beasts, bulls and lambs and horses dancing to the altar to die in the worship of the Gods. Black, like the splashed blood of the sacrifice.

Before dawn the watchers had cried that the signal fires were burning to announce the return of Agamemnon, son of Atreus, from the sack of Troy. I went out, wrapped only in a thin chiton, and sighted the points of greedy light on the surrounding hills. He had been long away, my father, the King of Mycenae, and many things had happened in his absence.

She had taken a lover. Queen Clytemnestra, my mother, had welcomed into her bed the revenge child Aegisthus, my uncle. He was the son of incest between his father Thyestes, brother to my father, and his own daughter, a priestess of the river. He existed to enact his father's vengeance on the House of Atreus, for Atreus' murder of Thyestes' children. Before he came, I had not known how well I could hate.

I hate very well.

Part of me did not really believe that she could kill him. My tall father, dazzling in his bronze armour, tall as a giant, strong as a bull. When he had gone with the army to harry Troy, ten years before, I had been twelve and a child, believing that the world was a safe place for Laodice, called Electra, Princess of Golden Mycenae. I had given him my bunch of windflowers and he had fastened them on the shoulder of his harness. He had picked me up and hugged me, smelling of leather and wine, and I had snuggled closer to him, begging to be allowed to come, at least as far as Navplio and the beaches where the black ships lay, keel to keel, waiting for the wind.

Later I was glad that he had denied me that sight. We sent my sister Iphigenia, my gentle, beautiful sister, out of the gate of the lions, with rejoicing and the music of bells, for her marriage with the hero Achilles. Instead she had been espoused by Thanatos who is Death, the Dark Angel. She was sacrificed on the altar of Boreas, the north wind, so that my father's ships could sail to Troy; so that the revenge of the sons of Atreus for the kidnapping of the faithless Elene should fall on that stone city.

The nightmare began the night we heard of her death.

My mother Clytemnestra did not scream or cry. No tears fell from eyes that became more and more stony as the days went by. She did not speak or eat for three days, then she arose and stalked the walls. She stared out, towards the sea, towards Tiryns where Dikaios the Just ruled. I did not know what she was looking for.

Now, ten years later, I know. The beacons were blazing for the return of the king. My mother's order, my mother's fire, whipped on by her will. From Lemnos to Athos, Makistos to Messapion across Euripos, Kithairon to the Gorgon's Eye, burning Ida to the Black Widow's mountain, Spider Peak above Mycenae, which always threatens to topple but never falls.

The cloth was laid for the sacrifice; the double axe was in my mother's hands. I shivered in the chill light of dawn, looking out over the silvery olive groves, my hands on the balustrade thawing the ice-rimmed stone, and listened to the morning noises.

A cock crowed 'Kou kou ra kou!' I could hear Orestes, my dearest brother, singing the morning song to Eos who is the dawn. Somewhere a man was whistling on the cold hills; a goatherd was piping calling-tunes to his herd. Running feet, well shod, sounded in the chill courts of Mycenae and I smelled hearth smoke and the scent of baking bread. But there was a misplaced sound among the morning noises, a regular, gritty sliding sound just behind me.

With mountain stone and virgin oil, Clytemnestra was whetting the axe.

Cassandra

The bearers stopped for breath at the foot of a steep gravel path in the middle of what seemed to be a market. I looked out of the litter, in which I was tethered by a chain about my neck. A captive of Lord Agamemnon must not be allowed to escape. She might be valuable; especially if she is, was, a Princess of Troy.

The traders carried firewood and skewers of meat and sandals and tripods. I could smell dust and roasted flesh and charcoal fires, unwashed humans, pine trees, wine and amber oil. Now that the religious hush which greeted the return of the Great King had passed, the noise of the crowd hurt my ears.

I looked up to a narrow gate, surmounted with two lionesses carved out of grey granite. For a moment I flinched. The massive walls seemed about to fall and crush me. The road wound past the feet of the Cyclopean walls and curved up the hill. The bronze doors were open.

Above us the city rang with harping and singing, and some enthusiast was hooting through a bronze trumpet. Long strips of delicate weaving, blue and black and crimson, fluttered from the walls and flapped in the chill breeze. Mycenae was evidently pleased that Agamemnon was home in triumph from Troy.

I was part of his triumph. A most unwilling part.

I had seen the city - my city - sacked and burned. Agamemnon's army had slaughtered my brothers and taken my sisters as slaves. He had taken me also, disgraced Priestess of Bright Apollo, torn me from my twin Eleni, who was closer than any lover.

Agamemnon was bringing Cassandra, daughter of Priam, home to his queen and his city, to draw water for his horses for the rest of my days. I listened to the sea-sound of wind in the olives, remembering Ocean, and the buzzing of flesh-flies in the pines.

I had almost escaped. The priest of Asclepius, Diomenes called Chryse, and the Trojan ex-slave, Eumides, had fished me out of the water. Agamemnon, however, had not drunk any of the drugged wine with which I had put my ship to sleep.

We heard a bull's roar over the water, 'Find Cassandra!' I had slipped back into the ocean, to avoid compromising my friends. Even then I swam quite a way to shore before they caught me.

Chryse and Eumides had sworn, in hurried whispers, that they would follow and rescue me, but I had seen nothing of them on the long road. I did not expect help from them. I trusted their good hearts, but anything might have happened to them - storms at sea had scattered the fleet, several ships had been lost, and we had been repeatedly attacked by bandits on the long road from Navplion.

I recalled the chain of little hot lights, fire speeding across the mountains to announce the return of the Sons of Atreus. King Agamemnon had sighted them too, far out on the wrinkled sea, flat as a plate, the seamen grunting at the oars.

'There goes the message of my victory,' he said, and grinned.

I hated him. Big as a bull, strong, coarse, brutal, cunning king. He had tried to rape me the night of my recapture, but I had called on the black aspect of Gaia the Mother, the Goddess Hecate, Drinker of Dog's Blood, and the proud phallus had shrunk and fallen under her black regard, the snake-haired one.

For disgraced or not, captive or not, exiled or at home, I am still Cassandra, daughter of Priam of the Royal House of Troy, Priestess of Apollo, and I can call on the Gods. They owe this to me, who have wounded me almost beyond bearing.

Agamemnon had attempted violation again the next night, when I was seasick; perhaps he thought that I would have less power if I was retching helplessly. The other women had urged me to co-operate, saying that he would beat me, but I would not. He disgusted me, his matted chest, filthy skin still smeared with Trojan blood, and his grasping, sweaty hands.

And when he shoved me down and knelt again between my thighs to no effect,