We use compensation as the most efficient means to transform Yakut parallelism typical of the epic language into English parallel constructions:

Buhra Dokhsun oburgu,

Who has never been tamed,

Whose father is Sung Jahin,

Who has the thunder chariot,

Who flashes lightning! (Song 7)

Compensation also helped much in our attempts to transfer so-called ‘parnyie slova’ – a rhymed couple of words where the second component does not have any meaning and is added only for rhyming purposes but in our version both components have meanings:

The eight-rimmed, eight-brimmed,

Full of discord-discontent,

Our Primordial Motherland

Was created-consecrated, they say…

So, we do our best to tell the story… (Song 1)

A Sakha mountainscape

As mentioned above, some Yakut turcologists felt suspicious of the quality of the English translation of the Yakut epic because they believed that it was impossible to transfer all the richness and depth of the Yakut language into another language, especially an unrelated one. In response to this view, it is appropriate to cite the words of Roman Jakobson: ‘All cognitive experience and its classification is conveyable in any existing language. Whenever there is deficiency, terminology may be qualified and amplified by loan words and loan translations, neologisms or semantic shifts, and finally, by circumlocutions.’ [R. Jacobson, ‘On the Linguistic Aspect of Translation’, 1959.] This implies that in order to convey the same notion expressed in the Yakut language by a single term, a speaker of English must resort to employing different lexical strategies, such as circumlocution, neologisms and/or loanwords. Our English translation keeps some exotic words where there were lexical gaps -- for example, when expressing units of measures (kes, bylas). To avoid transcribing too many Yakut words we add their English equivalents, e.g. ‘илии’ [i’li:] is translated as ‘finger-sized’; ‘тутум’ [tu’tum] is translated as ‘fist-sized’, a hitching post for horses, is represented in two versions – both ‘sergeh’ and ‘tethering post’; the dwelling is either translated as ‘uraha’ and sometimes as ‘yurt’, being a more familiar word to English-speaking readers; the utensils ‘чорон’, ‘хамыйах’ and ‘кытыйа’ are represented by their English analogues ‘(wooden or silver) cup’, ‘bowl’ or ‘flat bowl’. The Yakut ‘кымыс’ [ki`mis] is also translated as one of the more traditional English forms ‘kumis’. All fire-spitting, many-legged and many-headed monsters translated in previous Olonkho translations as ‘serpent’ and/or ‘snake’ I translated as ‘dragon’, which is closer to the real nature of these creatures. All such transformations were necessary to concentrate the reader’s attention on the unfolding plot, which is already overwhelmed with bright unusual images and metaphors.

Onomatopoeic words and interjections brought their contribution to complicate the English translation: ‘Uhun-tusku!’; ‘Urui-aikhal!’; ‘Ker-bu! Ker-bu!’; ‘Buia-buia, buiakam!’; ‘Buo-buo! Je-buo!’; ‘Anyaha-anyaha!’; ‘Art-tatai!’; etc. The only exception we made was for the interjection ‘Хы-хык! Хы-хык! ([hi-`hik])’, transferred as ‘Ha-ha!’. In some cases we used explanations translating the meaning of interjections: ‘Look here’, ‘Listen to me’, etc.

The following example, taken from a draft translation of the Olonkho, shows how we tried to keep imagery and metaphors, i.e. the so-called ‘picturesque words’ in the translation:

| Орто дойду улуу дуоланаАан ийэ дайдытыттанАрахсан барда,Аабылааҥҥа тиийдэ,Күнүн сириттэнКүрэнэн истэ,Туналҕаннаах толооноТуoһахта курдукТуналыйан хаалла... | The great giant of the Middle WorldHad leftHis primordial Motherland,And come to the thicket,He was running awayFrom the sunny land,The bright surface of whichWas shining far behindLike a white patch on a cow’s head… |

This fragment describes Nurgun Botur’s journey to the Under World, while the sunny Middle World is left behind shining brightly as a white patch on a cow’s forehead. The picturesque word ‘туналый’ means ‘whiten/shine’, ‘lighten/glisten’, ‘radiate/beam’, and as such its semantic structure consists of the components ‘glisten, shine’ and ‘white colour’. The translation of the verb keeps only the component ‘shine’, but its second component is compensated in the word combination ‘Like a white patch on a cow’s head’.

Another one of the serious issues was the translation of polysemantic words which are used profusely in the Olonkho. For example, the word ‘түhүлгэ’ [tjuhjul`ge] – ‘tuhulgeh’ has a few meanings that hamper the choice of the right word: 1) a place where a festival is celebrated, or where people dance their round dance ohokai, which also refers to the name of the dancing circle, or a place for wrestling, or an Olonkho performance, etc.; 2) the festival itself, i.e. it can be a synonym for the summer solstice festival Esekh or any other fest (wedding party, etc.). Thus, in Song 9 the word has all the meanings simultaneously but I had to choose a concrete one and it was the festival Esekh:

They made

A wide and vast,

Joyful and bright

Esekh festival – tuhulgeh

On a beautiful copper surface

Of their blessed Motherland…

In conclusion, the Olonkho is a text with a high percentage of national-cultural components that make the process of translation extremely difficult.

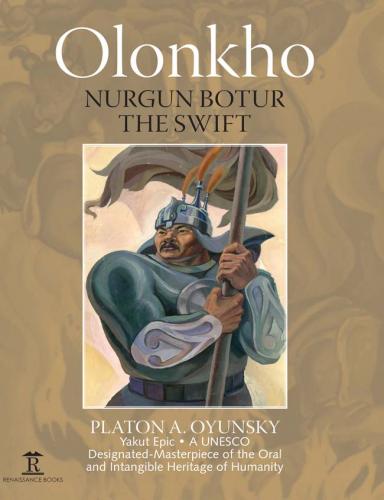

An Olonkho hero

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to the Government of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), Ministry of Culture and Spiritual Development of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) and to the M. K. Ammosov North-Eastern Federal University for their financial and moral support of my project.

An Olonkho-teller improvising a fight

This translation would not have been possible without the advice and assistance generously provided by various people. First of all, my special thanks are extended to the Chancellor of M.K. Ammosov University, Professor Dr Evgeniya Isaevna Mikhailova; to the First Vice-Minister of Culture and Spiritual Development of the Republic, Tuyaara Igorevna Pestryakova, who believed in me from the very beginning; to Professor Vasily Vasilievich Illarionov, a world-leading expert in Olonkho who encouraged me to translate the Yakut epic; to Professor Tamara Ivanovna Petrova; to Dr Lyudmila Sofronovna Zamorshikova; to Yuri Petrovich Borisov, a researcher of the Olonkho Research Institute, NEFU, Yakutsk – all these experts in the Sakha language who led me to a deeper understanding and appreciation of the Olonkho and who were a greatly appreciated source of moral support. I would also like to mention Dr Robin Harris’ approval and enthusiasm towards this project, and her precious initial ideas, which included referring us to a proofreader.

I also wish to acknowledge the help provided by the