Lastly, the everyday has the peculiar property of being made up of slight and singular moments, little one-off events—situations—that seem to happen in between more important things, but which unlike those important things tend to flow into each other and connect up, flowing, finally, into some apprehension of a totality—a connection of sorts between things of all kinds. The trick is to follow the line that links the experience of concrete situations in everyday life to the spectacular falsification of totality.

These days extreme commuters may be working while they travel. The cellphone and the laptop make it possible to roll calls while driving or to work the spreadsheets while on the bus or train. They allow the working day to extend into travel time, making all of time productive rather than interstitial. Isn’t technology wonderful? Where once, when you left the office, you could be on your own, now the cellphone tethers you to the demands of others almost anywhere at any time. Those shiny phones and handy tablets appear as if in a dream or a movie to make the world available at your command. The ads discreetly fail to mention that they rather put you at the world’s command. The working day expands to fill up what were formerly workless hours and spills over into sleepless nights.

The thread that runs from the everyday moment of answering a cellphone or pecking away at a laptop on a bus to the larger totality plays out a lot further. Where do old laptops go to die? Many of them end up in the city of Guiyu in China’s Pearl River Delta, which is something like the electronic-waste capital of the planet. Some sixty thousand people work there at so-called recycling, which is the new name for the old job of mining minerals, not from nature, but from this second nature of consumer waste.

It is work that, like the mining of old, imperils the health of the miners, this time with the runoff of toxic metals and acids. In Guiyu, “computer carcasses line the streets, awaiting dismemberment. Circuit boards and hard drives lie in huge mounds. At thousands of workshops, laborers shred and grind plastic casings into particles, snip cables and pry chips from circuit boards. Workers pass the boards through red-hot kilns or acid baths to dissolve lead, silver and other metals from the digital detritus. The acrid smell of burning solder and melting plastic fills the air.”28 The critique of everyday life can seek out otherwise obscure connections between one experience of life and another, looking for the way the commuter on a laptop and the e-waste worker melting chip boards are connected. It considers the everyday from the point of view of how to transform it, and takes nothing for granted about what is needed or what is desired.

2 The Critique of Everyday Life

What good is knowledge if it isn’t practiced? These days real knowledge lies in knowing how to live.

Baltasar Gracián

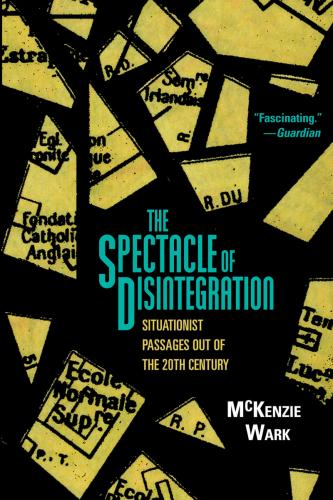

Henri Lefebvre started this line of thought with his 1947 book The Critique of Everyday Life Volume 1 and raised it to a fine pitch with that book’s second volume in 1961. But the group who really pushed it to its limit was the Situationist International, a movement which lasted from 1957 until 1972, and which its leading light Guy Debord would later describe as “this obscure conspiracy of limitless demands.”1

While their project was one of “leaving the twentieth century,” in the twenty-first century they have become something of an intellectual curio.2 They stand in for all that up-to-date intellectual types think they have outgrown, and yet somehow the Situationists refuse to be left behind. They keep coming back as the bad conscience of the worlds of writing, art, cinema and architecture that claim the glamour of critical friction yet lack the nerve to actually rub it in. Now that critical theory has become hypocritical theory, the Situationist International keeps washing up on these shores like shipwrecked luggage. Are the Situationists derided so much because they were wrong or because they are right?

Consider how their legacy is isolated and managed. The early phase of the Situationist project, roughly from 1957 to 1961, is safety consigned to the world of art and architecture. Its leading lights, such as Pinot Gallizio, Asger Jorn, Michèle Bernstein and Constant Nieuwenhuys, all have books and articles dedicated to managing their memory.3 The period from 1961 to 1972 is considered the political phase, and its memory is kept by various leftist sects who reprint the writings of Raoul Vaneigem, Guy Debord and René Viénet, and are mostly concerned with the critique of each other.4 Of more interest to us now perhaps is Post-Situationist literature, in which former members or associates, including T. J. Clark, Gianfranco Sanguinetti and Alice Becker-Ho, restate or revise the theses of the movement, which runs more or less from 1972 to Debord’s death in 1994.

The life and work of Guy Debord, the one consistent presence in the movement, is fodder for all kinds of recuperations. For biographers he is a grand grotesque, or a revolutionary idol, the hipster’s Che Guevara. Certain enterprising critics have turned him into a master of French prose.5 By recuperating fragments of the Situationist project within the intellectual division of labor, its bracing critique of everyday life as a totality, not to mention the project of constructing an alternative, tends to disappear into the footnotes.

In 2009 the French Minister of Culture, Christine Albanel, declared the archive of Guy Debord a national treasure. The archive, in the possession of Debord’s widow, Alice Becker-Ho, contains a holograph of Society of the Spectacle, reading notes, notebooks in which Debord recorded his dreams, his entire correspondence, and the manuscript of a last, unfinished book, previously believed to have been destroyed. Yale University had already expressed interest in acquiring the archive, prompting the Bibliothèque Nationale, or French National Library, to make securing the Debord archive a priority.

The fund-raising arm of the Library holds an annual gala dinner to hit up its big benefactors for cash, and its 2009 event displayed Debord notebooks to tempt donors. Present were several board members, including Pierre Bergé (co-founder of Yves Saint Laurent) and Nahed Ojjeh (widow of the arms dealer Akram Ojjeh). Only E180,000 was raised, a fraction of what the Library had to find for Becker-Ho. “This evening depends upon the spectacular society,” fund-raising chief Jean-Claude Meyer admitted in his speech. “It’s ironic and, at the same time, a great homage.” But if the Library could make an archive out of the Marquis de Sade, then anything is possible. The gala dinner took place in the Library’s Hall of Globes, a monument to the presidency of François Mitterrand, who Debord particularly detested.6

The gulf that separates the present times from the time of the Situationist International passes through that troubled legacy of the failed revolution of 1968 and 1969 in France and Italy, in which Situationists were direct participants. There was no beach beneath the street. Whether such a revolution was possible or even desirable at that moment is a question best left aside. The installation of necessity as desire in the disintegrating spectacle is a consequence of a revolution that either could not or would not take place.

Even if a revolution could not take place in the late twentieth century, in the early twenty-first century it seems simply unimaginable.7 It is hard not to suspect that the over-developed world has simply become untenable, and yet it is incapable of proposing any alternative to itself but more of the same. These are times in which the famous slogan from ’68—“be realistic, demand the impossible”—does indeed seem more realist than surrealist.

And yet these are times with a very uneasy relation to the legacy of such intellectual realists. Debord in particular is at once slighted and envied, as he was even in his own time. He was, by his own admission, “a remarkable example of what this era did not want.”8 He seemed to live a rather charmed life while doing nothing to deserve it. Debord: “I do not know why I am called ‘a third rate Mephistopheles’ by people who are incapable of figuring out that they have been serving a third rate society and have received in return third rate rewards … Or is it perhaps precisely because of that they say such things?”9

Not the least problem with Debord is that of all the adjutants of 1968 he was the one who compromised least on the ambitions of that moment in his later life. “So I have had the pleasures of exile as others have had the pains of submission.”10 Unlike Daniel