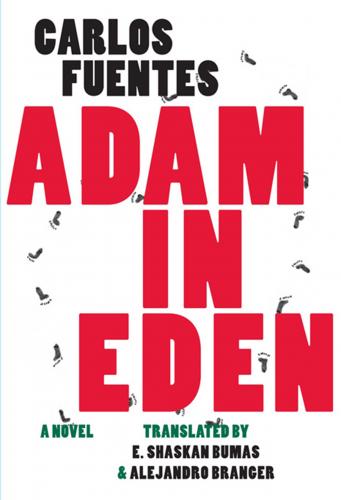

ADAM

IN EDEN

CARLOS FUENTES

TRANSLATED BY

E. SHASKAN BUMAS AND

ALEJANDRO BRANGER

Dedication

Did I request thee, Maker, from my clayTo mould me Man? did I solicit thee From darkness to promote me, or here place In this delicious garden?

—Milton, Paradise Lost

Contents

Dedication

OTHER WORKS BY CARLOS FUENTES IN ENGLISH TRANSLATION

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

About the Authors

Copyright

OTHER WORKS BY CARLOS FUENTES IN ENGLISH TRANSLATION

Where the Air is Clear

Aura The Good Conscience The Death of Artemio Cruz A Change of Skin

Holy Place Terra Nostra The Hydra Head Burnt Water Distant Relations

The Old Gringo Christopher Unborn Myself with Others The Buried Mirror: Reflections on Spain and the New World

The Campaign The Orange Tree Diana: The Goddess Who Hunts Alone A New Time for Mexico The Crystal Frontier: A Novel in Nine Stories

The Years with Laura Díaz Inez This I Believe: An A to Z of a Life

The Eagle’s Throne Happy Families Destiny and Desire

Vlad

Chapter 1

I don’t understand what happened. Last Christmas everybody was smiling at me, giving me gifts, congratulating me, predicting a new year—yet another year—of success, satisfaction, and just rewards. People nodded approval at my wife as though to tell her she was very lucky to be married to the toast of the town . . . Today I ask myself, what does it mean to be “the toast of the town . . . ?” Or, for that matter, burnt toast? I feel more burnt than toasted. Was this the year when my memory, so subject to illusions, at last grew disillusioned? Did what happened really happen? I don’t really want to know. All I want is to go back to last year’s Christmas: a family affair, comforting in its stark simplicity (in its inherent stupidity) and annual reoccurrence; a prophecy of twelve months to come that would not be as gratifying as Christmas Eve because fortunately they would not be as silly and wretched as Christmas; the holiday that we celebrate in December—just because—as a matter of course—without knowing why—out of custom—because we are Christians—we are Mexicans—war—war against Lucifer—because in Mexico we’re Catholics to a man, not excepting the atheists—because a thousand years of iconography instructs us to kneel before the Nativity scene of Bethlehem even as we turn our backs on the Vatican. Christmas takes us back to the humble origins of faith. There was a time, another time, when to be Christian was to be called an atheist, to be persecuted, to hide, to flee. Heresy: a heroic path. Now, in our sorry age, to be an atheist shocks no one. Nothing is shocking. Nobody is shocked. What if I, Adam Gorozpe, were suddenly to knock down the little Christmas tree with my fist, smash the star, wrap a wreath around my wife Priscila Holguín’s head as a crown, and—as they used to say—to drum out (whatever that means) my guests . . . ?

Why don’t I do that? Why do I keep acting with my famous bonhomie? Why do I keep behaving like the perfect host who, every Christmas, invites friends and colleagues over, plies them with food and drink, gives each of them a different present—never the same tie twice, or the same scarf—even as my wife insists that ‘tis the season for re-gifting the useless, ugly, or duplicate presents that were foisted on us, and for dumping them on those who, in turn, give them to other dupes who thrust them upon . . .

I look at the small mountain of gifts piled before the tree. I am overcome by the fear of giving a colleague the gift he gave me two, three, four Christmases ago . . . But thinking about this is enough to ward off my fears. My story isn’t up to New Year’s yet. It’s still Christmas Eve. My family surrounds me. My innocent wife smiles her most conceited smile. The maids pass around punch. My father-in-law distributes cake and cookies from a tray.

I should not get ahead of myself. Today everything is fine; nothing awful has happened yet.

I look out the window distractedly.

A comet trails across the sky.

And my wife, Priscila, loudly slaps the maid who serves the cocktails.

Chapter 2

Again a comet shoots across the sky. I am paralyzed with doubt. Is the bright heavenly body preceded by its own light or does it merely introduce the light? Does the light mark the beginning or the end? Does it presage birth or death? I believe the sun, the greater celestial object, determines whether the comet is a before or after. In other words: the sun is the master of the game; the comets are specks, chorus members, the extras of the universe. And yet, we are so accustomed to the sun that we only notice its absence, its eclipse. We think about the sun when we do not see the sun. Comets, though, are like launched rays of solid sunlight, emissary beings, ancillaries to the sun, and in spite of everything, proof of the existence of the sun: without servants, there is no master. A master needs servants to prove his own existence. I ought to know. As I am a modern lawyer and businessman who can vouch for my whereabouts five times a week (Saturday and Sunday being holidays), taking my place at the head of the conference table, my subordinated subordinates spaced before