Recognition goes to Bruce and Lucy Baker, and Herbert and Sylvia Benz for serving as my footprints to my German translator, Rainer Hoeh who shares the understanding and importance of this work. Thanks too for Sylvia and Herbert’s willingness to serve as readers for the German translation.

To my family, the Aschoffs, Schaefers, and Reinharts, as well as my friends who offered patience, understanding, and words of encouragement during the three years of this project I thank you all.

The Meditative Readings and the Great Vision narrative are excerpts from “The 1931 Interviews by John G. Neihardt” published with the permission of the John G. Neihardt Trust and the Western Historical Manuscript Collection, University of Missouri-Columbia, Columbia, MO.

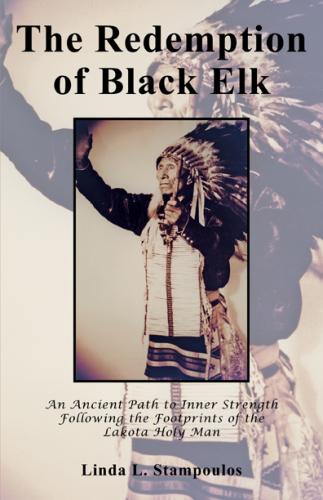

All photographs were provided with the permission of the Western History’s Collection, Denver Public Library.

I am going to tell you the story of my life and if it were only the story of my life I think I would not tell it, for what is one man that he should make much of his winters even when they bend him like a heavy snow?

But now that I see it all as from a lonely hilltop, I know it was the story of a mighty vision given in my youth to a man too weak to use it; of a holy tree that should have flourished in a people’s heart with flowers and singing birds, and now is withered; and of a people’s dream that died in the bloody snow. It was a beautiful dream.

But if the vision was true and mighty, as I know it is true and mighty yet; for such things are of the spirit, and it is in the darkness of their eyes that men get lost.

You see me now a pitiful old man who has done nothing; for the nation’s hoop is broken and scattered. There is no center any longer, and the sacred tree is dead.

O Great Spirit, I recall the great vision you sent me. It may be that some little root of the sacred tree still lives. Nourish it then, that it may leaf and bloom and fill with singing birds. Hear me not for myself, but for my people; I am old. Hear me that they may once more go back into the sacred hoop and find the good red road, and the shielding tree. O make my people live!

Excerpts from “Black Elk Speaks by John G. Neihardt” with permission of the John G. Neihardt Trust and the Western Historical Manuscript Collection, University of Missouri-Columbia, Columbia, MO.

This outdoor photograph of Black Elk was taken in 1936 by Joseph G. Masters. Photo is provided courtesy of the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, Call Number X33351.

Introduction

Most texts devoted to self-help and self-exploration concern themselves with providing tools and exercises for individual application to today’s problems. The approach taken in this book is to lift you up and carry you back to a time when America was experiencing perhaps the greatest upheaval of its indigenous populations and their culture. Provided are Meditative Readings that serve as your window to the past; eyewitness accounts of benchmark events in the history of the West.

But this is much more than an historical recording. By exploring the first hand accounts, the author discovered an ancient pathway woven into the images of that time. What surfaced was a series of metaphorical footprints left behind by a man named Black Elk.

As a young child of the Oglala Lakota Sioux, Black Elk had been given a vision; a mighty vision which would lead him on a personal journey intended to result in the peace and flourishing of his people. He was born in December of 1863, the year tribes recorded as, “The Winter when the Four Crows Were Killed.” Far to the east America was engaged in the great Civil War. Very little attention was given to happenings in the West.

During his early childhood, Black Elk and the people of the Sioux Nation were free to live their lives as they had for centuries. As a boy he learned to fish, to hunt and use a bow, to ride, and to take part in the celebrations so vital to the life of the tribe. A simple man, Black Elk never learned to read or write, he spoke only Lakota, yet amazingly this one simple man would live to experience more cultural upheaval in his early years than most of us would experience in a lifetime.

Over the course of his life, Black Elk would find himself at the Battle of the Little Big Horn; at Fort Robinson when his cousin, the great leader Crazy Horse, was killed; in exile with Sitting Bull and Gall; and at Wounded Knee during the time of the Ghost Dance movement and the Great Massacre. He was witness to the government’s unrelenting efforts to take from the Lakota their sacred Black Hills, and even beyond the land, their very way of life.

With the help of his mighty vision, Black Elk was able to unfold symbols and metaphors in very unique ways so that the lessons learned built on one another and, in the end, laid out before us an ancient path toward inner strength and a balanced life. Black Elk’s symbols and metaphors present themselves in guises or clothes that often must be peeled back or carefully removed to discover the messages they contain. There is nothing new here; basic truths that exist throughout time. The challenge is to lift those meanings from one generation into another so that in re-examining them we too may have the direction, a way for us to go.

Black Elk’s life was truly a journey. It began some one hundred and twenty five years ago, it had about it a sacredness that must never be forgotten, because for him it was never forgotten. Now, however, as an old man of many winters, he pours forth a soulful lament of one who has done “nothing.” The once beautiful dream died in the bloody snow and without the fulfillment of the vision, his people will continue to be lost in the “darkness of their eyes.”

Great men, however, are never as far away from hope as they may think. So it is that up from the depths of his broken heart he once more pleads to Wakan Tanka, “If it may be that some little root of the sacred tree still lives, nourish it then that it may leaf and bloom and fill with singing birds.” Black Elk died believing the dream was lost. But this is far from the truth. It was impossible for him to see how with each step of his personal journey he left a footprint for us to follow. Step by step the way has been made for each of us.

Why then, would this man who lived over a century ago need redemption? The answer is as simple as the life he lived: The rediscovery of a dream. Black Elk’s vision was a prophetic message telling the terrible future of his tribe. But his vision also held positive aspects that must be reclaimed. It is through this reclamation that the guiding beacons given to him will cause the ancient path to rise up out of the bloody snow and show the way for us…125 years later. He thought the message of the vision would die with him, but it can be brought to life again through us.

The journey we travel in life is certainly not new. History tells us of those who traveled before, each with their own set of problems. But history can also tell us how people throughout the centuries found ways to cope with their problems. That message can be as important, if not more important than the history lesson itself.

Why not, then, examine someone else’s journey and discover the ancient path they took? Someone like Black Elk, who experienced enormous problems: harsh winters, lack of food, battles with neighboring tribes, the encroachment of White soldiers who were intent to strip away his entire way of life. Yet he found a pathway to overcome them; and by doing so, reaches across a century of time and points the way for us.

Our problems are in no way similar. For most of us, the problems concern themselves with interpersonal relationships, lack of money, employment, and health. It is in this highly technological world, that we become increasingly separated from the ability to see a path and lead a balanced life.

The messages of