Sale of Last Bike

My time came in Japan about 12 years ago at the age of fifty-six. It was a fateful day in the fall of 1993 for yours truly, and all five-feet-eight inches of my brown-haired, blue-eyed, athletic, wiry and, otherwise, nondescript self. I remember standing on the sidewalk in front of the house watching a friend by the name of Jack Owen drive off on my last bike… as its new owner. Jack and I had been riding companions for many years in the Camp Zama Motorcycle Club of Sagamihara, Japan. It was a U.S. Army, Japan (USARJ) sponsored club located South of Tokyo – but more about that later. I was surprised that Jack bought my 1987 Kawasaki Ninja 750 R, since he already owned a Yamaha 1150cc Virago. Perhaps he wanted to try a sport bike with the front-leaning driving position for a change, or maybe he just liked the looks and performance of it.

One year later, however, he sold the Ninja and kept his Virago. I guess he didn’t like the front-leaning rest position after all. It takes some getting used to as compared to the upright sitting position of the Yamaha. The difference in posture equates to the difference between a sport bike and a cruiser. I never asked him why he sold it, and he never divulged his rationale. We parted company that day, and we had infrequent contact with one another for the next few years. The bike was the common denominator, you see, and when that link was severed, there was little basis for continuing our relationship. Work and other interests caused our paths to diverge and diluted our friendship. I eventually transferred to a new job and location back in the States and totally lost contact with my friend for several years.

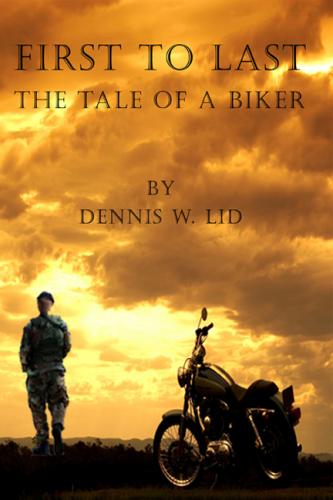

As Jack drove the sleek, black, Kawasaki Ninja away from me and into the sunset that fateful day, he took a piece of my heart as well. He drove up the sidewalk and onto the road. I watched until he was out of sight, shading my eyes with my hand as bike and rider were silhouetted against the setting sun. Even after I could no longer hear the turbo-like drone, the heartbeat of the vertical four, I stood in place for a long time holding the check from the sale of my geisha, as I was fond of calling her. Now she was gone; there would be no replacement. The impact of that fact began to sink into my consciousness, as I stood there motionless. My eyes looked without seeing anything, like the “thousand-yard stare” of a warrior after the battle subsides. It dawned on me that the time had come to “hang up my spurs” and end my riding days.

It would take a while for me to really grasp the significance of that realization. After sharing the better part of my lifetime with the iron horse, what would I do without one? The weekends would seem to be a bit listless and empty; the camaraderie of riding companions non-existent. Good-bye to new motorcycle adventures, the adrenaline rush and the accumulation of fresh memories of the good times. Why then, must I stop riding now? The reasons that contributed to that conclusion will eventually surface during this journey of a biker’s tale. Part of it has to do with the challenge, the search, the quest that I mentioned earlier, but there’s more to it than that. All that’s left now, and since that fateful day, is the memory of the motorcycles I once owned and the great times I had on all of them… from First to Last. Yet, the quest for the Holy Grail continues. Perhaps it’s a relentless search until the very end – until one draws one’s last breath.

The prelude that ushered in my motorcycling days resided in the Thornhill Drive neighborhood where I grew up, my friends and our group activities. These elements, to one degree or another, were all instrumental in leading to my way of life as a motorcyclist.

Our neighborhood included a group of about 14 boys who were relatively the same age. My family moved into that neighborhood when I was seven years old. I became the best of friends with all the boys. We did practically everything together from forming our own Cub Scout Den to joining the same Boy Scout and Explorer Troops as we progressed through the years to high school age. We played all the usual games that kids play during our younger years, from football and baseball to kick-the-can and bicycle hikes. We built tree houses, made rafts, boats, and down-hill racing coasters, dug tunnels, ran cross-country bicycle courses complete with jumps, curves, water obstacles and mud traps, went on BB Gun hunts to kill lizards and snakes, and camped out under the stars on many a summer night. We were a tough and raucous bunch of daring rascals and pretty good at just about everything we tried to do. I guess you’d call us “hardcore,” and therein lay one essential ingredient of a true motorcyclist.

Other essential aspects of a true motorcyclist began to emerge as well. All the things we did required planning, organization and action of one kind or another. A few of my friends and I were the leaders of the groups we formed for specific tasks during our games and activities. We did the planning and directing; then we and our groups followed through with action to complete the tasks. Leadership, and the formation of organizations and elements for a common purpose, would prove to be useful skills later in my life when it came to planning motorcycle trips and events, and organizing clubs, rides and activities. So then, leadership, organizational and planning abilities are still other essential aspects of a true motorcyclist. These talents and skills were developed during the prelude to my motorcycling days in the crucible of my youth. The neighborhood, my friends of bygone days and the activities we engaged in formed the foundation of and threshold to the world of motorcycling.

My life as a motorcyclist really began in earnest when I got a learner’s permit for driving from the State of California at age 14. The permit allowed me to use a motorbike or moped to ride solo. Convincing my parents that I needed such a conveyance was critical but not difficult. My most persuasive argument was that I had a rather long newspaper route in the Montclair Hills between Oakland and Orinda. These rugged hills were part of the Coast Range Mountains running along the seacoast of Northern California. We lived on one of the many ridge fingers descending from the Skyline on a road called Thornhill Drive. The views were spectacular along the upper portions of Thornhill toward its juncture with Snake Road, which in turn, connected to Skyline Boulevard on the highest ridge of the Coast Range Mountains. One could see the entire San Francisco Bay area from these vantage points including the Golden Gate and Bay Bridges, Treasure and Alcatraz Islands, San Francisco, Oakland and the entire bay.

The newspaper route for the Post Enquirer was several miles long and went from the top of the ridge at Snake Road along Thornhill Drive to the bottom of the gulch near Mountain Boulevard. I needed dependable transportation to negotiate this route on a daily basis. My three-speed racing bike had been used for this task up until the time that I bought my first motorbike with proceeds from paper-route earnings, lawn cuttings and car washings. It was the paper route that gave me the edge in convincing my parents that the moped was a sound investment for business purposes. Of course, it provided for pleasure trips as well. The motorbike saved time and effort. It was a more efficient way of delivering newspapers and of making monthly monetary collections for the service. Albeit, it was probably a less frugal method of delivery because of gasoline, license, insurance and maintenance costs, but the time and effort saved were devoted to my school studies instead. Owning a bike also taught me driving responsibility, safety and how to take care of a vehicle.

I learned how to drive safely and responsibly in two ways: First, by taking a safe driving course for motorcyclists, and second, by on-the-road driving experience. The course actually came years after the actual driving experience for the simple reason that there were no formal motorcycle safety courses during my youth. These courses were established years later in response to the rising number of motorcycle accidents. I finally took such a course at Camp Zama, Japan during March of 1986 to renew my motorcycle license and reduce my insurance premium. The course concentrated on driving techniques such as counter-steering, emergency braking by evenly applying both front and rear brakes, maneuvering to avoid obstacles, recognition of international