In January 1957, just before Macmillan replaced Eden, a retired Conservative MP, Christopher Hollis, noted that Eton had ten times as many MPs and ten times as many members of the government than any other school, a disproportion greater than before 1832. He did not think this was inherently undesirable. At the height of the Suez crisis, it was Etonians – the Macmillans’ son-in-law Julian Amery and future brother-in-law Victor Hinchingbrooke among the hawks, Jakie Astor, Boothby, Edward Boyle, Anthony Nutting among the doves – who had the courage to refuse blind loyalty to Eden’s blunders. Hollis argued ‘that in a generally egalitarian society, those who have positions of responsibility will be apt to be too timidly conformist and that a few Old Etonians about the place, bred in a tradition of liberty, ready in their very insolence to value other things above immediate success, are no bad leaven to the general lump’. Hollis had been an intelligent, independent-minded MP who had retired at the 1955 general election because he had not received political advancement, probably because he was suspected of homosexuality. Such was the parliamentary party’s fearful recoil from unorthodox opinions or temperament that, as one young backbencher later recalled with shame, ‘had I been more mature I might have benefited from his friendship, but as it was I brushed him off as swiftly as I decently could’.36

Responding to Hollis, Henry Kerby, a Tory backbencher with links to MI5, stressed the importance in party counsels of men whose families were neither traditional gentry nor hereditary nobility, but had got their wealth, and possibly recent titles, from shareholdings in large businesses. ‘The House of Commons is packed with Old Etonians who are no more members of the aristocracy than I am. The Government benches are crowded with Members of Parliament who are Old Etonians only because their fathers could afford to send them to that school.’ These MPs were ‘representatives of a moneybags plutocracy, however much many of them may try to disguise their origins. The House is crammed with first-generation descendants of hard-faced men who have done very well for themselves in trade of every sort – honourable and otherwise.’ (Kerby’s point was backed by a survey in 1959 of the country houses in Banbury district, just south of Profumo’s constituency of Stratford-on-Avon, which found that of the forty-three houses large enough to be named on the one-inch ordnance survey map, only four had been in the same family for more than two generations.) Constituency selection committees, continued Kerby, were ‘dumbstruck’ by the sight of prospective candidates sporting the black ties, with thin blue stripes, that showed the old Etonian. They realised that young men, with that particular fabric round their necks, would quickly reach political patronage and power. ‘Money,’ Kerby complained, ‘lies at the bottom of Old Etonian dominance.’37

Angus Maude, a Tory MP who would succeed Profumo at Stratford, explained that once constituency parties were debarred from extracting election expenses and big subscriptions from candidates, they instead demanded that MPs spent more time in constituencies attending to local fusses. Old Etonians, with inherited incomes that exempted them from the need to earn a living, had the free time that constituency associations required. Moreover, the MPs who were most likely to reach office were those who could devote most time to politics. ‘OEs’, overall, had more free hours than professional and company director MPs. There was a higher proportion of OEs in government posts than on the backbenches because of the low pay of junior ministers: many MPs could not accept office without financial hardship. Macmillan’s government, Maude calculated, had seventy ministers, of whom about ten might be called ‘self-made’. This scarcely mattered, he argued, because ‘a parliamentary party consisting entirely of very clever men would prove the devil to run and might prove extremely dangerous’.38

‘Those who hope to rule must first learn to obey,’ a Harrow housemaster had written thirty years earlier. ‘To learn to obey as a fag is part of the routine that is the essence of the English Public School system, and … is the wonder of other countries. Who shall say it is not that which has so largely helped to make England the most successful colonising nation, and the just ruler of the backward races of the world?’ The instinctive, automatic obedience to their leader felt by most Tory MPs was based on fear of party whips, who reminded them of prefects brandishing canes, or of scragging from other backbenchers. Mark Bonham Carter described his experience after being elected in a Liberal by-election coup in 1958. ‘It’s just like being back as a new boy at public school – with its rituals and rules, and also its background of convention, which breeds a sense of anxiety and inferiority in people who don’t know the rules. Even the smell – the smell of damp stone stairways – is like a school. All you have of your own is a locker – just like a school locker. You don’t know where you’re allowed to go, and where not – you’re always afraid you may be breaking some rule … It’s just like a public school: and that’s why Labour MPs are overawed by it – because they feel that only the Tory MPs know what a public school is like.’ Robin Ferrers, who was appointed as a lord-in-waiting by Macmillan in 1962, found front-bench life just like school. ‘There are the clever guys. There are the silly clots, too. Like football, you do the best that you can when the ball comes to you in order not to let the side down. At Question Time, if you can make them laugh, it is very satisfying. The schoolboy ethos is never far away – and that is good.’39

Sticklers resented any challenge to the prefects’ authority. When a decision of the Deputy Speaker’s was criticised by Lady Mellor, wife of a Tory MP, at a garden party, Labour MPs complained, and the Commons Privileges Committee censured her. No words that might weaken house esprit de corps could be tolerated, especially from anyone as objectionable as a woman with forthright and informed views. During crises, the Conservative parliamentary party resembled a boarding house in which any boy who challenged the housemaster’s decisions would be biffed or given a bogging. Even in private sessions, it was bad form to bestir the deferential placidity. When Macmillan, or his successors Douglas-Home and Heath, addressed the 1922 Committee of backbenchers, questions were confined to the closing minutes of the meeting. The questions seldom exceeded the level of those at a constituency ward meeting.40

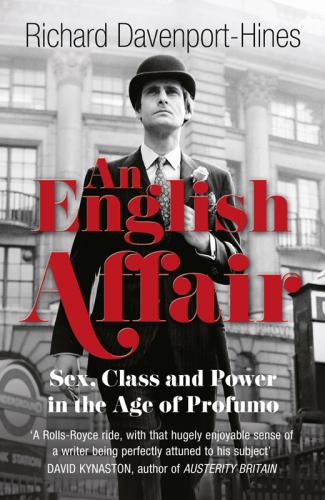

There was a striking homogeneity in the appearance of the Conservative parliamentary party: MPs wore a uniform of stiff white collars or cream silk shirts; dark, well-pressed suits or a black jacket with striped black and grey trousers; sleek Trumper’s haircuts and oils. On Fridays, which were called Private Members’ Days, when government business was not taken, and the Commons was thinly attended, the Conservative whips wore weekend tweed suits and brogue shoes. Julian Critchley was once standing in the crowded ‘No’ lobby, waiting to vote, when Sir Jocelyn Lucas, a crusty baronet who bred Sealyhams, accosted him, seized his elbow, hissed ‘You’re wearin’ suede shoes’, and stalked off. Lucas never addressed Critchley again. Excessive importance was attached to social standing. ‘Some able middle-class Conservatives – like Enoch Powell or Iain Macleod – have gone a long way,’ Anthony Wedgwood Benn commented in 1957, ‘but one senses that many Tory MPs would prefer to be in the top drawer and out of office than to be out of the drawer and in office.’41

Once he became Prime Minister, Macmillan began attending the Derby, cricket matches, and other jollities to settle his image with his party faithful. He excelled in striking poses which projected his personality until it was a palpable force over others. The Tory die-hards had not been fooled by so brilliant a man since Disraeli. His address to Tory peers before the general election of 1959 was ‘the best speech I think I have ever heard from a leader addressing his followers’, noted blimpish Lord Winterton, who had fifty-five years’ parliamentary experience. There were sweeping historical parallels to flatter his auditors’ intelligence, and patriotic pride to rouse them. In international affairs, Britain was speeding towards danger ‘like a man on a monorail’, Macmillan warned the peers, ‘but mankind had never known security save perhaps in Antonine age of Ancient [Rome] & Victorian age’. The achievement of full employment with ‘one of the highest standards of living in the world’ by a nation with few natural resources was possible because Britain was ‘rich in brain power as in the time of the first Elizabeth when Europe looked on us as Barbarians who couldn’t use a fork’. The Lords – backwoodsmen and activists alike – were rallied by such High Table urbanities.42

Critchley recalled a dinner that was