Slowly she turns and surveys her new home. A year, rent-free, in exchange for looking after an ancient house with mullioned windows and a moss-covered slate roof and an old and grumpy cat called Pepper. Overwhelmed with unexpected happiness she begins to smile.

‘He’s too old to go into a cattery, Andy. It would kill him. He needs to stay at home. He needs someone to feed him regularly and make sure the house is warm. That’s all. He won’t need anything else. He’s his own man. Well, his own cat! And he knows you.’ Sue’s voice was pleading, though she had already known that Andy would say yes.

Yes, the cat had met her. Once. For a couple of weeks when she and Graham had stayed here with Sue four summers ago. Andy’s smile faded at the memory, then it returned. In her head, for a moment, the house was full of the sound of Sue’s irrepressible laughter and Graham’s deep guffaws.

Exhausted after the long drive, she sat down on the cold stone slab of the top step and, hugging her knees, stared down over the almost vertical wild rock garden which fronted the ancient stone building, down towards the parking space, no more than a lay-by really, off the narrow lane, occupied now only by her old Passat. She could see the low sun glinting on its dark blue roof, almost hidden by the tangle of autumn flowers. The car contained almost all she owned in the whole world.

She hadn’t expected this – to be suddenly and irrevocably homeless.

‘It’s your fault he died!’ Rhona Wilson, Graham’s widow, shouted at Andy. ‘If he had never met you we would have been happy. He would be alive now.’ It took Rhona’s sister, Michelle, to drag her away as Andy stood there, numb with shock, too overwhelmed with grief to move.

‘Get out of our house!’ Michelle almost spat the words at Andy. ‘Go. Haven’t you done enough damage here, stealing Graham away from us? Killing him!’

Andy backed out of the room, turned and ran down the stairs. She shouldn’t have been surprised. She knew Rhona hated her. The woman had left Graham long before Andy had come into his life, run off with another man, left him as well and moved in with a second, followed that one to the States, come back with someone quite different, but never had she lost her sense of ownership. She didn’t want Graham, but she didn’t want anyone else to have him either and she obviously didn’t intend to let anyone else benefit, if that was the right word, from his death. In the past she had contented herself with the odd vitriolic phone call, occasional nasty letters and postcards, but in the past Graham had been there to protect Andy. Now he was gone and Rhona had found allies in her war of attrition.

Andy’s life had been idyllic. She had lived with Graham for nearly ten years in his beautiful detached house in the quiet tree-lined street in Kew. She wrote her column for the local paper. She illustrated his books, fulfilling her contractual duties as his co-author by providing exquisite, tiny watercolours of the exotic rare plants he wrote about. That was how she had met him; his publisher had contacted her with a suggestion that she might be the person to illustrate his next book. She was happy. He was happy. Then the cancer came, swift and deadly, diagnosed far too late.

Within days of his death his ex-wife, technically still his wife, and her family had made it clear that Andy had no place, no rights, no security, no home.

She didn’t even know they had keys to the house; they were in before she realised it. They tried to stop her taking even her own things, this vicious greedy cabal of women, his wife, her sister, her friends. They had supervised her packing, had checked everything as she threw her cases and bags into her car. They grabbed her sketchbooks and paintings. Graham had paid for them, they screeched, though technically they had not yet been paid for; she was contracted to his publisher. She didn’t argue. Didn’t fight back. Did not care. He was gone. She doubted she could live without him anyway.

But then the phone calls had started and the threats had continued even though Andy had left the house. Rhona was sure she had stolen things. But, if there had been theft it was not on Andy’s side. Graham’s will, and Andy had seen his will, leaving his house and garden and books and manuscripts to her, had disappeared. The solicitor, Rhona’s sister’s husband, as it happened, said he had no copy and knew nothing of it. Andy gave up. She wouldn’t, she couldn’t, fight them.

To escape Rhona’s vicious calls she kept her phone switched off. She slept on sofas and floors and drank a great deal of wine with her mother and her wonderful loyal friends as she tried to come to terms with the fact that she had no home, very little money, no future and, it seemed, no past. Without her friends to steady her, replace the rock which had been Graham, she would have been a wreck, if she had survived at all.

Then Sue had phoned. She had heard what had happened on the grapevine. ‘I’m not sure if this would be a port in a storm, Andy. If you like the idea it would surely help me. I planned this trip to Australia to go to my brother’s wedding and then spend time visiting the folks, blithely assuming I could get a tenant in time. I’d much rather it was you than a stranger, and Rhona will never find you in Wales.’

And so, here she was. Rubbing her face wearily Andy stood up, conscious of the roar of water from the brook that ran along the edge of the garden, plunging over rocks and between deep overhanging banks thick with moss and fern, under the bridge in the lane and on down towards the valley.

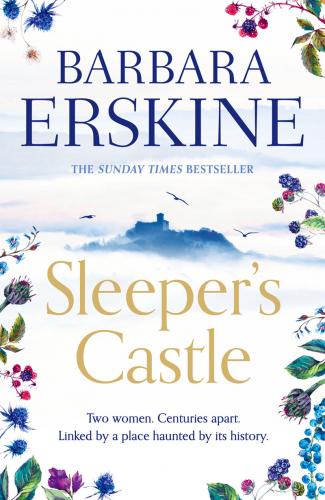

The house, with its wonderful romantic name of Sleeper’s Castle, was in the foothills of the Black Mountains, a few miles from the nearest town. The countryside was huge and empty and the contours on the map had been, as she reminded herself on her way here, suspiciously close to each other, a clue to the presence of steep hills and deep secluded valleys. Sue called it her retreat. She had no neighbours. None close by, anyway.

Andy turned her back on the endless view of misty hills and the turbulent sky and she made her way towards the front door, past the rough wooden bench which stood with its back to the stone wall, facing the view.

Sleeper’s Castle was not, never had been, a castle, but it had once been a much bigger house. The name Sleeper’s, Sue had told her vaguely, came from something in Welsh. It didn’t matter. It was perfect. Wild, unspoilt, magical, built on the eastern fringe of the Black Mountains, the remote, mysterious range at the north-easternmost end of the Brecon Beacons National Park, on the Welsh side of the border between England and Wales. Andy took a deep breath of the soft sweet upland air and infinitesimally, without her noticing, the first of her cares began gently to drop away.

Nowadays the downstairs of the house comprised only four rooms, the largest by far, which had once been the medieval hall, paying lip service to its duties now as a sitting/living room only by the presence of an enormous baggy inelegant sofa and a couple of old, all-enveloping, velvet-covered armchairs. Smothered with an array of multi-coloured rugs they had been arranged in a semicircle around a huge open fireplace built of ancient stone, topped by a bressummer beam, split and scorched from countless roaring fires over many centuries. At the moment the fireplace was empty and swept clean of ash but the sweet smell of woodsmoke still clung in the corners of the room and hung about the beams. The rest of the room, with its oak table, bureau bookcase, ancient kneehole desk and scattered multi-dimensional chairs served Sue as a potting-shed-cum-office. Andy gave a wry smile. She had lived with a plantsman for years, but never once had he allowed his garden to encroach on the elegance of his home. His wellies – and hers – stayed firmly in the utility room at the back of the house. Where hers still were, she realised with a pang of misery. Here, judging by the state of the threadbare rug, Sue still wore hers indoors. The fact that there was a mirror on the wall was somehow counter-intuitive.

Andy caught sight of herself and briefly she stood still, staring. Her shoulder-length wild curly light brown hair stood out round her head in a tangled mass, her eyes, grey and usually clear and expressive, looked sore and reddened with exhaustion and misery. Her face, which Graham used to describe as beautiful, was drawn and sad. She was not a pretty sight. She stepped back with a grimace, turned her back on the mirror and with a last, affectionate glance round the room made her way through to the kitchen.

It