“I’ll tell you who’s stupid!” Billy shouted angrily. “You want me to punch your lights out?”

Before I knew what was happening, Billy lunged at Shane.

But no quailing from Shane. He lunged back. “Yeah! I wanna beat your head in!” he shouted. “I’m gonna pound you to a bloody little zit on the sidewalk and then step on you!”

“Yeah!” Zane chimed in. “Me too!”

And I was thinking, Gosh, this is going to be a fun year.

I was pathetically glad to see Julie when she showed up at one o’clock. The morning had been nothing but one long fistfight. Shane and Zane, who were six, had arrived in the classroom with a diagnosis of FAS – fetal alcohol syndrome – which is a condition that occurs in the unborn child when alcohol is overused in pregnancy. As a result, they both had the distinctive elflike physical features that characterize fetal alcohol syndrome, a borderline IQ, and serious behavioral problems, in particular, hyperactivity and attention deficit. Even this glum picture, however, was a rather inadequate description of these pint-size guerrillas. With their manic behavior, identical Howdy Doody faces, and weird, out-of-date clothes, they were like characters from some horror film come to life to terrorize the classroom.

Jesse, who was eight, had Tourette’s syndrome, which caused him to have several tics including spells of rapid eye blinking, head twitching, and sniffing, as if he had a runny nose, although he didn’t. In addition, he obsessively straightened things. He was particularly concerned about having his pencils and erasers laid out just so on his table, which was not a promising road to happiness in this class. The moment the others realized it mattered to him, they were intent on knocking his carefully aligned items around just to wind him up. Also not a good idea, I discovered quickly. His obsessiveness gave Jesse the initial impression of being a rather finicky, fastidious child. However, beneath this veneer was a kid with the mind-set of Darth Vader. Things had to be done his way. Death to anyone who refused.

Compared to these three, Billy seemed rather tame. He was just plain aggressive, a cocky live wire who was willing to take on anyone and everyone, whether it made sense or not; a kid whose mouth was permanently in gear before his brain. Permanently in gear, period.

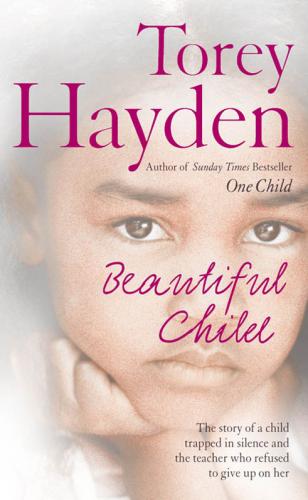

I’d been forced to more or less ignore Venus over the course of the morning because I was too busy breaking up fights among the boys. She didn’t appear to mind this inattention. Indeed, she didn’t actually appear to be alive most of the time. Plopped down in her chair at the table, she just sat, staring ahead of her. I’d offered some papers and crayons at one point. I’d offered a storybook. I’d offered a jigsaw puzzle. Admittedly, all this was done on the run, while chasing after one of the boys, and I’d had no time to sit down with her, but even so … Venus picked up whatever it was I’d given her and manipulated it back and forth in a sluggish, detached manner for a few moments without using it appropriately. Then, as soon as I turned away, she let it drop and resumed sitting motionlessly.

Once Julie arrived, I gave her the task of refereeing the boys and then took Venus aside. I wanted to get the measure of Venus’s silence immediately. I wasn’t sure yet if it was an elective behavior that she could control or whether it was some more serious physical problem that prevented her from speaking, but I knew from experience that if it was psychological, I needed to intervene before we developed a relationship based on silence.

“Come with me,” I said, moving to the far end of the room away from Julie and the boys.

Venus watched me in an open, direct way. She had good eye contact, which I took as a positive sign. This made it less likely that autism was at the base of her silence.

“Here, come here. I want you to do something with me.”

Venus continued to watch me but didn’t move.

I returned to her table. “Come with me, please. We’re going to work together.” Putting a hand under her elbow, I brought her to her feet. Hand on her shoulder, I directed her to the far end of the room. “You sit there.” I indicated a chair.

Venus stood.

I put a hand on her head and pressed down. She sat. Pulling out the chair across the table from her, I sat down and lifted over a tub of crayons and a piece of paper.

“I’m going to tell you something very special,” I said. “A secret. Do you like secrets?”

She stared at me blankly.

I put on my most “special secret” voice and leaned toward her. “I wasn’t always a teacher. Know what I did? I worked with children who had a hard time speaking at school. Just like you!” Admittedly, this wasn’t such an exciting secret, but I tried to make it sound like something very special. “My job was to help them be able to talk again anytime they wanted.” I grinned. “What do you think about that? Would you like to start talking again?”

Venus kept her eyes on my face, her gaze never wavering, but it was a remarkably hooded gaze. I had no clue whatsoever as to what she might be thinking. Or even if she was thinking.

“It’s very important to speak in our room. Talking is the way we let others know how we are feeling. Talking is how we let other people know what we are thinking, because they can’t see inside our heads to find out. They won’t know otherwise. We have to tell them. That’s how people understand each other. It’s how we resolve problems and get help when we need it and that makes us feel happier. So it’s important to learn how to use words.”

Venus never took her eyes from mine. She almost didn’t blink.

“I know it’s hard to start talking when you’ve been used to being silent. It feels different. It feels scary. That’s okay. It’s okay to feel scared in here. It’s okay to feel uncertain.”

If she was uncertain, Venus didn’t let on. She stared uninhibitedly into my face.

I lifted up a piece of paper. “I’d like you to make a picture for me. Draw me a house.”

No movement.

We sat, staring at each other.

“Here, shall I get you started? I’ll draw the ground.” I took up a green crayon and drew a line across the bottom of the paper, then I turned the paper back in her direction and pushed the tub of crayons over. “There. Now, can you draw a house?”

Venus didn’t look down. Gently I reached across and reoriented her head so that she would have to look at the paper. I pointed to it.

Nothing.

Surely she did know what a house was. She was seven. She had sat through kindergarten twice. But maybe she was developmentally delayed, like her sister. Maybe expecting her to draw a house was expecting too much.

“Here. Take a crayon in your hand.” I had to rise up, come around the table, grab hold of her arm, bring her hand up, insert the crayon, and lay it on the table. She kept hold of the crayon, but her hand flopped back down on the table like a lifeless fish.

Picking up a different crayon, I made a mark on the paper. “Can you make a line like that?” I asked. “There. Right beside where I drew my line.”

I regarded her. Maybe she wasn’t right-handed. I’d not seen her pick up anything, so I’d just assumed. But maybe she was left-handed. I reached over and put the crayon in the other hand. She didn’t grip it very well, so I got up, came around the table, took her left hand, repositioned it better and lay it back on the table. I returned to my seat. Trying to sound terribly jolly, I said, “I’m left handed,” in the excited tone of voice one would normally reserve for comments like “I’m a millionaire.”

No. She wasn’t going to cooperate. She just sat, staring at me again, her dark eyes hooded and unreadable.

“Well, this isn’t working, is it?” I said cheerfully and whipped the piece of paper away. “Let’s try something