For many first-hand witnesses to the breakneck pace of change after the fall of the Wall, the transformation formed a significant part of their life stories, but they also found it an odd experience. It’s uncanny living in a city you could tell many stories about if only you could mould them into a narrative.

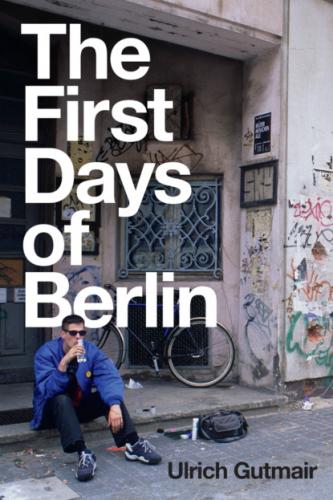

That was Brad’s experience (full name Sung-Uk Bradden Hwang). In 1990 this art student, who grew up in rural Utah, moved from Los Angeles to Berlin, where he didn’t know a soul. He had no money and he didn’t speak German. Brad used junk to build gadgets whose function was determined by the meaning observers ascribed to them. He viewed his artworks as gifts: ‘Giving away the very things you don’t have to people who can’t pay for them.’

Brad constructed a potato-waffle-throwing machine from a trolley normally used for transporting bottles of welding gas. He made a portable lightning machine. For Café Zapata at Tacheles he built ‘The Singing, Soup-Cooking Heating System’ out of steel barrels, its secondary function being to heat the café. A reporter from Der Spiegel noted in 1991 that the artwork created something of a stir. When the journalist asks him why he came to Berlin, Brad doesn’t understand the question. ‘Hier isset, man’ (‘This is where it’s at, man’) is his comment – he’d picked up Berlin dialect and specific countercultural slang in record time. The new energy, unification – ‘It’s one helluva fix’, he says.

Twenty years on, Brad is still in Berlin. He, his wife and their two kids live on a houseboat called Odin. In 2011 he posted a text titled ‘Ghost Investigation’ online. In it he tries to explain why there is so little record of his work from the period after the Wall fell. His conclusion is that it wasn’t necessary.

‘When all’s said and done, we would collect food and junk in the mornings, visit friends before lunch (and scribble something on the door if they weren’t in) to talk about that day and the weather and everything else in life, make music for a bit around noon, hook up to the neighbours’ running hot water in the afternoons, cook a meal and eat together in the evenings, dance the nights away, sleep. The next day we would go looking for coal briquettes, queue up outside with a phone we’d found or borrowed to connect it to a recently discovered working line, organize or play at or go to a gig, paint or look at pictures, sleep for a bit longer the day after that, make music again or DJ, more cooking and eating, no hot water after all, try again.’ How are you meant to document all those things when artistic production is such an integral part of an unfathomable routine, Brad wonders. ‘No matter, tomorrow’s another day.’

He’s still haunted by the ghosts of the post-Wende years. ‘Where have Mayakovsky’s wonderful life or Beuys’s social sculptures gone? Where has the classless society gone? Didn’t something happen? We sensed the ghosts in the darkness, on the edges of our vision, again and again, in moments of upheaval and unrest, but we cannot grasp them. The normal strategy seems to be to explain them away. Atemporality should at last be recorded as history; at the end of the day, it’s the only thing we can embrace, archive, sell or forget.’ Brad Hwang quotes Octavio Paz: ‘Anyone who has looked hope in the eye will never be able to forget it. He will search for it wherever he goes.’ Brad Hwang thinks these ghosts wouldn’t haunt us if they didn’t have something important to whisper to us.

Klaus is one such ghost. You would often see him standing by the bar in Elektro at Mauerstrasse 15, three underground stations from Oranienburger Tor, before he started sitting by the kiosk opposite Tacheles. The vacant plots next to the Elektro were covered with grasses and fast-spreading invasive plants, the prettiest and most conspicuous of which was staghorn sumac. The staghorn, known to botanists as Rhus hirta or Rhus typhina, belongs to the Anacardiaceae family. It was introduced to Europe from North America in 1602 and first planted in Germany in 1676. It has now spread across the entire country. It has light-coloured wood and is easy to recognize from afar by its feathery leaves. It thrives in Berlin’s sandy soil, its roots forming rambling rhizomes.

There was constant building going on in Berlin. Wherever, not so long ago, there had been a vacant site, full of grasses and staghorn sumac, wherever no gardener was keeping things in check because the site’s ownership was unclear, wherever heirs were at loggerheads, speculation was rife or an investor had gone bankrupt years ago: a couple of weeks later, the foundations of a new building would have been poured. The empty plots disappeared under the new buildings, taking the staghorn and the memories with them.

The disappearance of the gaps and holes in Mitte refutes many historians’ claims that only remembering is a productive process and that forgetting befalls us automatically. The vacant plots reminded Mitte’s residents of the destruction of the war. Their loss represented the loss of a historic space, an amnesia that corroded the urban environment. While he was alive, Klaus was both a witness and living testament to the fact that all of this had once existed on the corner of Mauerstrasse and Kronenstrasse, where an office block now stands and nothing remains to remind people that this was once one of the liveliest, most productive places in Mitte.

‘I find it hard to remember the places I used to go and what they looked like’, Christoph Keller says. ‘I’ve really blocked it all out. I’d love to climb inside one of those ghost houses now and take a look around. I also get the years muddled up. Later, they put up scaffolding in front of the houses, and it would be in place for a year. Then they’d take it down again and behind it there’d be something completely new. It’s like after a war: I can’t reconnect with the old geography.’

People have different opinions about what happened to the city after the Wall came down. Regarding what came next, though, there is one thing all Mitte’s residents can quickly agree upon: it is impossible to square the memories with the reality.

‘This happens repeatedly throughout history’, Christoph Keller says. ‘People repress memories after wars or other periods of upheaval. A similar thing has happened here because there’s been such a turnover in the population of Mitte and because the buildings are no longer here to bear witness. It all happened so fast. By the end of the nineties, you could only talk in the past tense.’

The disappearance of the vacant plots was symptomatic of this repression in two ways: where the vacant sites were redeveloped, forgetting began; and where the gaps were still visible or people remembered them, conversations began.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.