It was late already and we had been given the going-home ultimatum. Perhaps this was why my guard was down. I went over to the showers to wash the salt and sand off, when I felt a stabbing pain in the sole of my right foot. Lifting it up to look, I saw droplets of blood coming from a pinprick in my instep. I didn’t go digging around in the sand; I knew perfectly well what I’d stepped on. I went the rest of the way to the shower on tiptoes and held the sole of my foot under the running water until the bleeding stopped. Really, there were barely three drops of blood, but it hurt like a stake had been driven through me.

You’re limping, what’s wrong? said my mother, handing me my sandals as I put on my t-shirt.

I didn’t answer. I got into the car in silence and didn’t say a word all the way back, or when I was in the shower at home, or putting my pyjamas on, or over the reheated green beans from the previous day, or when I was left alone in my bedroom after the good night, sleep tight.

I turned on the bedside lamp and examined my foot. There, almost in the exact centre of the sole, was the dot: circular and, to anyone who didn’t know what they were looking for, invisible. I turn out the light and slept a peaceful sleep. There was no anguish, no desire to tell anyone about it. I was going to die gaunt and dishevelled, like an actor or a petty thief. There was nothing to be done: I had AIDS.

I resigned myself to not seeing another summer. I packed away my swimming trunks and turned my thoughts to autumn, convinced I would never set foot on a beach again. I put my jumper on believing that I would not be having Christmas dinner that year in my grandfather’s village. I went about saying goodbye silently, secretly, with no feeling of drama, no mise-en-scène. Waiting for death seemed like waiting for any other thing, such as break time at school or a doctor’s appointment.

But months went by, and I just kept on not dying. Another summer came, and then another, and I started to grow stubble, and my voice dropped, and I stopped being a child any longer, and still my heart went on pumping. But neither clocks nor calendars averted my belief in my sentence: death was only being deferred, I hadn’t escaped it. The AIDS virus was lurking somewhere in my body, just waiting for the right thing to spark it. Its belated arrival was because it knew I didn’t care, and it wanted to creep up on me just when I forgot about having stepped on the needle, because death is a lover of tragedy and of mise-en-scène and has no time for woebegone types who neither tremble nor weep nor beg for someone else to be taken in their place.

When Patricia read my palm and described that short, deep life line, I said nothing about the red dot on my right instep. I expected her to divine its presence, for it to shine forth to her mystically, like an agni chakra of the foot, but she was too tired, and she had her period and wanted to take a Nolotil, and no one in that state is going to perceive transcendent things. For all that I insist on the fact that witches aren’t human, all the ones I’ve met are possessed of a humanity that throbs within them just as my own does, and I’ve never been convinced that we can know other people when our own body is distracting us; it’s impossible to heed the pain of others if our own is constantly filling our ears.

Will Stalin see the red dot on my foot, with those Byzantine emperor eyes of his? On that devil card, small demons distract him by tickling his feet: the devil in the tarot always comes accompanied by such imps. Stalin’s knitted brow could be because he can’t scratch the places where the demons are touching him, as I scratched my arm, ripping off the scab, making it bleed again. The severe inscrutability of icons has never seemed like an attribute of power to me, but rather like the expression of the fact that something’s bothering them. It’s possible that Justinian and the awe-inspiring Pantocrators in Venetian churches don’t wish to strike their subjects down with a look, but that they’re doing all they can not to scratch. That Stalin wasn’t judging me, he was simply feeling uncomfortable and wanted to be alone so that he could scratch himself like an animal or go for a bath back at the dacha. Had I looked at the card more closely, I would have discovered a hint of sarcasm in his eyes, that compassionate mockery present in the glances exchanged by all who suffer skin conditions. I still didn’t know I was ill, but Stalin must have; after all, he was one of the major arcana.

Now I do know and I am going to tell my son about it. I will commit to the page these horror stories, which I still cannot play out for him at bedtime because the protagonists in these are monsters that do egg-siss, and that which is real, that which does egg-siss, is not the realm of children. Not because it will frighten them, but because they’re bound to get fed up with it when they cease being children, and everything then exists.

I read him a chapter from a Roald Dahl story every night. We range quite widely in the books we read together, but Dahl is our latest obsession. He has it the same as me: when he gets into a writer, he won’t stop until he’s read their entire body of work. Reading out loud means not only turning the words into sounds, but acting as well. I don’t put on voices to distinguish between the different characters, and I don’t sing the Oompa Loompa song, nor do I stretch out the vowels in an exaggerated way or gesticulate in slow-mo, in the manner of children’s storytellers who take children for people with brain damage. My particular mise-en-scène is far more subtle: at no moment do I cease being myself, and at the same time I am the narrator and all the characters. The metamorphosis comes about through imperceptible modulations in the voice, or so I believe, because I’m not completely clear about the moment in which my son stops hearing me and starts hearing the characters and the narrator.

Dahl has a way of tuning in to the wickedest frequencies in the personalities of children. Those who don’t know children tend to treat them like objects in a museum, things to be preserved in display cases and admired from afar, neither touched nor exposed to the elements; but anyone who dares to smell their breath knows that children can absorb bad things entirely unscathed, things that adults cannot stomach. It is us, the elders, who are afraid, because true fear can only arise out of experience. When confronted with debts we cannot pay, we’re afraid of going hungry. War frightens us because we have seen what it did to our grandparents. We’re terrified of illness, having cried at friends’ funerals. Fear without experience is nothing but a philosophical derangement, which is why children are never truly afraid. In the deepest recesses of every child there is an immaculate darkness, and Dahl knew how to combine words in such a way as to stimulate it. Fear, looked at like this, is funny for the child, but unbearable for the parent.

When I turn off the light and go out of his room, upon transforming back into what I am, I go and shelter in the books Dahl wrote for adults, which, like everything he did not write for children, is full of consolation and hope.

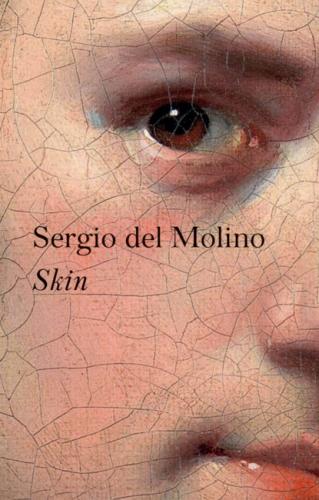

‘Skin’ is one of my favourites of his stories. Drioli, a small-time tattoo artist – I don’t know if there’s such a thing as a big-time tattoo artist – befriends Soutine, a Parisian painter who is just as small-time as him but has just sold his first paintings. To celebrate, they get drunk in the latter’s studio, and the night ends with Drioli offering his back as a canvas. He shows his friend how to do a tattoo, and Soutine paints a masterpiece on his skin. Many years later, Drioli passes an art gallery and is apprised of the fact that his friend, now dead, is a much sought-after artist. He has remained a wastrel, but he has a Soutine on his back. Drioli the old drunkard, beloved of no one, becomes a semi-priceless work of art. The skin on his back does, at least. I won’t spoil the ending, though it doesn’t take much to guess that it’s a gruesome one.

The Spanish translator opted to call it ‘Tattoo’, perhaps because it seemed to him more dangerous, thuggish and sinister than ‘Skin’, but this is a mistake, because the story isn’t about the tattoo but about the