The hammering of construction carried on next door, and I revised my novel, looking over the copy editor’s notes while considering the money I could make running guns or drugs. That kind of money would support my writing for a long time, though it might also mean I’d launch my book from behind bars. I was infuriated with myself for even considering it. I was a staunch believer in gun control.

During a telephone conversation with my editor, she asked about my life, and I was horrified to find myself telling her about these offers and their strange allure. I imagined that we’d make some jokes about Arthur Rimbaud, his transition from poetry to gun running in the Horn of Africa – that she’d understand the amoral impulse to adventure. She was silent. She said, “Mm-hmm.” We changed the subject.

One evening, after hours of walking, trying to exhaust my restlessness as the sun set over Montréal, I stopped at the grocery store. In the checkout line, I noticed my former neighbour in front of me, the one who howled. He was no longer ashen. He wore a new trench coat, clean black shoes, and a beret. When he turned and saw me, his eyes popped wide. He paid the cashier, took his bag, and hurried out.

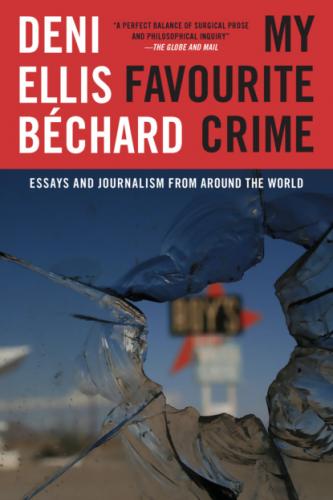

My Favourite Crime

(2012)

There’s a story my father often told me. I imagine most boys hear stories from their fathers, but not this sort. It was about a bank heist in 1967, the burglary of half a million dollars in West Hollywood. He called it the Big Job, an elaborate crime he’d started plotting when he was first incarcerated. Prison, he liked to say, turned him into a professional. He went in a petty crook and left wanting to do the Big Job, not unlike the way I went to college to study writing and left dreaming of the great American novel.

Born in 1938, my French Canadian father quit school in the fifth grade, his teenage years a gantlet of hard labour: fishing for cod, planting and harvesting potatoes, logging on the north shore of the St. Lawrence, pouring concrete on hydroelectric dams farther north, or mining uranium. During a construction gig in Montréal, as he walked the beam of a skyscraper, he watched his best friend trip and dive to the stone far below.

The next day he smashed his finger with a sledge, to get off the job with compensation. He drank in bars, trying to pick a new future, and finally befriended a criminal. He learned safe-cracking, claimed he was good, that he got set up for being too ambitious, betrayed while emptying the safe in a sporting goods store. As if the next two years of prison weren’t sufficient to complete a degree in crime, he added more, for armed robbery in Calgary and then Montana, before he headed to Los Angeles.

My father planned the Big Job for a night President Lyndon Johnson was in town, knowing the police would be busy. He rented an apartment overlooking the bank, parked a box truck in the alley next to it, and left it for a week, letting people get used to seeing it. On the night that LBJ addressed a crowd, my father’s partner backed the truck up to the bank’s barred bathroom window. Standing inside the box, my father cut the bars. Then he climbed inside, carrying a jackhammer.

His partner and his partner’s girlfriend both had walkie-talkies. The girlfriend followed my father inside while his partner watched the street from the apartment, warning her when cars passed so that she could signal my father to stop blasting at the concrete vault. My father opened a hole, slid himself in, and then threw the money out and broke open the security deposit boxes. But when he tried to leave, he couldn’t. The jackhammer had made a grain in the concrete that pointed inward, hooking on his clothes. He had to slide through naked, gouging his skin.

With his partner’s girlfriend, he drove to Nevada in the box truck. His partner stayed behind to make sure the surveillance apartment was clean. He was so afraid of leaving traces that he decided to burn the place down, even though this wasn’t part of the plan. As he splashed gasoline around the apartment, it dripped down to the stove’s pilot light. The place went up. His eyes were badly burned. The police caught him, and then my father, a year later, when he beat up a pimp in a Miami bar.

The first time my father told this story I was fifteen. “I thought I’d fooled life,” he said, confused, as if trying to see where it had all gone wrong. By then, he ran a seafood business – still a fisherman at heart, like his grandfather. I was disillusioned with him, wanting to be a writer, and he saw no point in this, or in school. I moved out to show him that I could survive as he had, leave my family and need no one.

I made my own way to college. I stopped bragging about being the son of a bank robber and started envying those who’d gone to boarding and private schools, whose parents paid for their education. And I wrote. When a Québécois professor read one of my stories, he told me he resented my fictional depiction of the French Canadian father as a ruthless criminal. I didn’t claim the truth as defence. And I didn’t write about my father again, at least not directly, until after my first novel was published. Then, when I no longer needed to separate the writer from the son, I wrote a memoir. I didn’t research his crimes; I just told the stories that shaped me.

Not long afterward, a fact checker with a magazine I wrote for sent me a Los Angeles Times article from 1967 about my father’s Big Job. It included a photograph: the bank manager peering through a jackhammered hole. But the vault that day held $70,000, not half a million, though seventy grand then would have been much closer in value to half a million when he was telling the story. Later reporting said two women as well as two men were arrested.

It doesn’t all fit, but I don’t particularly care. The Big Job was my favourite story, the gritty specifics a kind of proof of its truth, a lesson in storytelling.

My father died penniless, owing tens of thousands in back taxes. Friends have often jokingly asked if he stashed the money from the bank job and whether anything was left over for me. Now, fifty years after that crime, it seems that he did: not just a love for story and his stories themselves, but the gift of a relentless will to find my way, to test boundaries and take risks, not in violence or crime, but in books.

The Good People and Me

(2012)

It was two days before Christmas 1992. I was eighteen, and my father wanted me to meet my future bride even though I’d made plans to travel the continent.

“I got you an invitation to their Christmas Eve dinner.”

“You want me to have Christmas dinner with people I don’t know?”

“They’re good people, and she’s perfect. She’s blonde and was really good in school.”

“Come on,” I said. I was a good student only by his standards, and he was the one obsessed with blondes.

My father and I had never managed to figure out our relationship. As he encouraged me to get my life in order, he worked hard while courting ruin with reckless spending, reminding me of how, in a story he told, he pulled a near-perfect burglary but later got arrested for a bar fight.

But in the weeks before the Christmas dinner, he was different. If he drank, he talked of death. He made me promise to bury him in the mountains overlooking the ocean. He told me to lead a better life than he had. I suspected that the dinner was an attempt to keep me from travelling, but maybe he really wanted to offer me a better life.

The family’s last name was Goodman. This wasn’t a joke. After I arrived, Mr. Goodman talked to me in the basement where he played golf on an artificial green, knocking the ball into a cup that swallowed it and spit it back out.

Then we all gathered at the table: Swedish-looking Mr. Goodman, fluttery Mrs. Goodman, a heavyset family friend whose reddish highlights gleamed under the lamp, and Elana, like a 1950s actress in a yellow dress. I could feel her confusion, the entire family’s confusion.

Everything about them was good: