When June declared that they did not believe me she was within her rights, but for the wrong reasons. I did not fight back, although I might have used the opportunity to tell Parke and June the unvarnished truth; but within the topsy-turvy context of June’s disbelief (that the earth’s disinherited cannot acquire manners and education, or be gifted), the truth would have worsened my position because the truth was much worse than the “eccentric” half-truths I’d told her. And when June was convinced that she was right nothing could persuade her that she was wrong. And under certain kinds of attack, if the attacks come from women, I become paralyzed. I was paralyzed. I felt that June, and Parke with her, had unscrewed my head and filled my body with buckets of melancholy. I felt as helpless as a beaten child. I had no words. I don’t recall how I replied to the charges. Apologetically, no doubt.

On the other hand, I couldn’t bring myself to commit a version of suicide on June’s behalf. I clung to the identity I had disclosed; it wasn’t much, but it was all mine. June never stopped disbelieving it.

Aside from the stunningly classist (and positively un-American) attitude built into June’s disbelief, there was the partners’ ongoing conviction that if they battered long enough and hard enough at what I had indeed come from, and still was (despite the renovations I’d done on myself) they might eventually erase my difference from them—my origins, my memories, my history, and my people.

Doing away with my difference, the stuff of my human individuality and of my art, would also serve another vital purpose. Separate a writer from her typewriter and she’ll find a pencil; separate her from her autobiography, through disbelief, and she will become silent: and June knew it. The patriarchy had been successfully employing the technique for a long time.

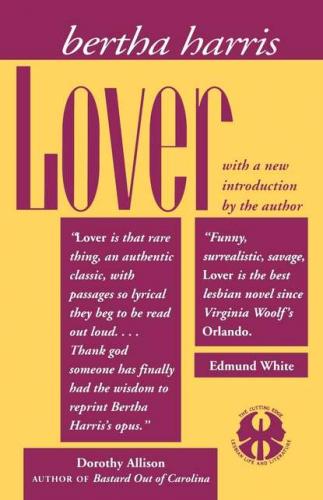

June and Parke had filled my days and nights with personal and professional crises; nonetheless, I was still writing. Furthermore, Lover was receiving the sort of critical attention June had craved for her second novel, The Cook and the Carpenter and for her third, Sister Gin. Worse, I was the second novelist published by Daughters who, June felt strongly, had gotten more attention than she deserved.

June and Parke became lovers in the late sixties. The first half of Daughters’ life was located in Plainfield, Vermont, where June owned a farm. Later, June and Parke moved into the top floor of June’s Manhattan loft building, but kept the farm. Parke bought the townhouse on Charles Street in Greenwich Village to serve as company headquarters; the Charles Street house also gave Parke a place absolutely hers to escape to when the fights with June, which were usually over June’s involvement with lesbian feminist politics and presses, began to escalate. Parke called sleeping at Charles Street “running away from home.” June had her own escape hatches. She would retreat to the farm or rent small apartments in the Village, where she wrote and saw movement friends privately. June’s politics had always made Parke nervous: that’s how Parke put it, “They make me nervous.”

Ironically, June’s politics are what brought them together. June was one of a group of women who, in the late sixties, took over a long-abandoned city-owned building on East Third Street and made it, rather comfortably, a shelter for women and a day-care center. When the city ordered them out, they resisted; the cops dragged them out. Parke was one of the lawyers who went downtown to get the women out of jail. Parke told me how June’s firebrand temperament initially thrilled her; how glamorous she seemed. But Parke’s romance with June’s temperament, and the politics which inspired it, was soon replaced by “nervousness,” which in fact was a fear (which would graduate into paranoia) of June’s drawing fire at the two of them from both the society at large and from parts of the movement June was at war with, which eventually included most of the women June had been with in the Third Street action.

June has been written about frequently, sometimes within the context of warm feminist praise for her fiction and her politics. Once in a while, a few details of June’s life are woven in with discussions of June’s books. It always interests me to find that the writers generally assume that June, with sterling altruism, deliberately turned her back on her Houstonian social rank and discontinued any immoderate personal use of her wealth once she became a feminist and a lesbian-feminist and a publisher of books by women: as if she had pulled herself down by the bootstraps.

In fact, June risked nothing, and lost nothing, when she left Houston for New York and the women’s movement. She had absolute control over her fortune, and very sensibly she never neglected to foster it. She never felt the cost of Daughters, nor did her generous handouts to feminist enterprises ever make a noticeable dent in her wealth. She enjoyed the enviable position of being able to indulge in charity (and buy alliances) without feeling the pinch of self-sacrifice. She once told me that she was always very careful not to give to feminist causes any of the money she meant her children to have. Her mother, she said, would want her grandchildren raised as much as possible as she had been, and well taken care of after her death.

When the partners decided to terminate Daughters, and retreat from New York into Houston, they might have sold the company to other women. That they did not allow Daughters to continue, in new hands, publishing women’s writing which might otherwise never see the light of day, was their revenge, their particular Tet offensive, against women in general and the women’s movement in particular.

As well as money, June brought to a movement determined to create equality not only with men, but among women, a profoundly inbred sense of superiority and a bottomless need to be recognized as an exceptional woman.

Born in South Carolina, October 27, 1926, June was raised in Houston, where she was a debutante; she went to Vassar but after a year transferred to Rice University back home in Houston. According to June, the Vassar girls were “snobs;” they didn’t regard Texans as their social peers. Attending Vassar was June’s first attempt to gain status in the Northeast: where status counted. Leaving Vassar was her first flight back to established, albeit provincial, status. June had all the well-known vanities, and thin-skinned pride, of the Texas millionaires. She often spoke of how “cultured” (despite the fact that they were Texan?) her mother, and her mother’s family, the Worthams, were. The family money was made in cotton and insurance. In Texas, cotton and insurance counted as “old” money. The parvenus were into oil.

After college and a tour of Europe, June married and bore five children, one of whom died in early childhood. She eventually divorced Mr. Arnold because, she told me, he was using up so much of her money in business failures. But not long afterward, according to what she told me, she went to New York and married a “Jewish psychiatrist” whose role as her New York husband, she said, was to give her an excuse to live in New York, away from her mother. June took her second husband down to Houston to meet the family. At the big barbecue thrown to fete the newlyweds, June’s new husband fell in love with all things Texan and refused to return to New York. So she divorced him too. Otherwise, June told me, she’d had lots of male lovers before she met Parke: which is the way it was, she explained, for pretty and popular Houston socialites in her day; she would rather have been a lesbian, of course, but she couldn’t find any lesbians to be a lesbian with.

One of the biggest and loudest fights the partners went through in my presence was about sex. It was bad enough, according to Parke, that June had had sex with men but she also suspected that a woman lover was lurking in June’s past. Parke hated the fact that June had had any lovers, male or female, before her. Sometimes Parke could, in a self-satirizing way, joke about her jealousy. I remember some madcap murderous schemes she came up with to punish June’s first husband for ever laying a hand on her.

I often felt that June, after the honeymoon wore off, was not at all happy with Parke sexually. Parke was a romantic and she had a romantic’s need for June to be the romantic’s ideal of